$27 Dollar Solutions for Lifting People Out of Crime

Crime is a source of great danger to our families, friends, values, and society. Five minutes of capricious violence can leave someone crippled for life or dead. A burglary can destroy a person’s feeling of security in their own home. We all want our criminal justice system to be effective and prevent crime. This article

is about evidence-based (proven to be effective) ways of preventing and lifting people out of crime.

In 1976 a young professor was teaching economics at Chittagong University in Bangladesh. As he drove through villages on his way to the university, he saw that many people were dying because of an extensive famine. At the sight of so much suffering, the professor questioned his economic theories. How could the economic system, which worked for so many, not work for the people in local villages?

The professor then reacted in an interesting way; he took his students out of the university and into a nearby village. They discovered that the village people knew how to work, how to raise their children, and how to create community, but they were so desperately poor that they could not get any financial help to lift themselves out of poverty. So the professor reached into his own pocket and took out the equivalent of $27 and gave it to 42 women. With $27 the women could now afford to buy materials for bamboo furniture, and through hard work and ingenuity they were able to make and sell the furniture, pay back the $27 loan, and still make a small profit that was enough to keep their business going and lift themselves out of poverty.

The professor, Muhammad Yunus, won the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006 for his work in setting up the Grameen Bank (see http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2006/yunus-bio.html), which today gives very small or “microloans” to more than 2 million people who are lifting themselves out of poverty.

What if we had $27 solutions that could lift people out of crime and make the public safer? What do I mean by $27 solutions? I mean approaches to the problem of crime that are

- More compassionate

- More effective

- Less costly than current criminal justice approaches.

Looking closely at the Muhammad Yunus story, we can see that his approach was more compassionate, more effective, and less costly than the existing economic approaches of his day.

The COSA Story

One concrete example of a $27 solution in the field of criminal justice is COSA, which stands for Circles of Support and Accountability. Begun in 1994, COSA consists of a circle of five to seven specially trained volunteers from the community who provide reentry support and accountability for people who are leaving prison and have a very high risk of committing new sexual offenses. COSA was started by Reverend Harry Nigh, a Mennonite pastor, in Hamilton, Canada, when a high-profile sex offender, “Tim,” was being released from prison after serving his sentence. Under Canadian law, Tim had to be released and would not be under any community supervision. Tim had met Pastor Nigh almost 10 years earlier during a prison visitation program. Because of his notoriety, Tim’s release had generated a great deal of newspaper coverage and community outrage.

Despite the dangerous nature of the case, Pastor Nigh agreed to offer Tim support, but he wisely asked several others from his faith community to join him. Pastor Nigh also began to work with a prison chaplain, Hugh Kierkegaard, to develop an approach to how COSA should work. Tim and the volunteers went on to develop a network of support, friendship, and accountability relationships in the community. Tim created a new life for himself, learned how to be a good neighbor again, and remained crime-free until his death from natural causes (O’Connor & Bogue, 2010).

COSA operates across Canada as a collaborative effort among volunteers from faith communities, community-based organizations, and the Chaplaincy Services Division of Correctional Service Canada (the Federal prison system in Canada). COSA volunteers work closely with chaplains, probation and parole officers, police, and psychologists. A rigorous evaluation of COSA in 2009 found that, compared to high-risk sex offenders who were released without COSA, the men in COSA had an 83 percent reduction in sexual offenses, a 76 percent reduction in violent offenses, and a 71 percent reduction in all offenses (Wilson, Cortoni, & McWhinnie, 2009).

A study of which correctional programs work by the Washington State Institute of Public Policy found that the COSA program had the largest reduction of recidivism among all of the 291 studies that it researched (Aos, Miller, & Drake, 2006). Evaluations of COSA have also determined that members of the community are more willing to accept the presence of a highrisk and high-need sex offender in their community if the offender is involved with a COSA circle (Wilson, Picheca, & Prinzo, 2007).

COSA, which has now spread to England and other countries, functions at a fraction of the cost of professional correctional and treatment programs for high-risk sex offenders. Because of COSA’s compassionate, community-based approach and its effectiveness and low cost, the Canadian government recently allocated an additional $8 million of funding to the prison chaplaincy division and its community partners to further expand and develop the program. COSA is a $27 solution that lifts people out of crime. It is more compassionate, more effective, and less costly than other alternatives that are currently available.

Ways of “Making Meaning”

The people who volunteer for COSA are motivated by their religious traditions. As David Brooks, a New York Times columnist says, “Faith motivates people to serve. Faith turns lives around. You want to do everything possible to give these faithful servants room and support so they can improve the spiritual, economic and social ecology in poor neighborhoods” (Brooks, 2012).

COSA, however, is not a religious or spiritual program in the sense of seeking to evangelize or use religious approaches such as scripture study. Neither is COSA an alternative approach to the criminal justice system. Instead, it is a partner with the criminal justice system that makes its own unique contribution to the system. COSA seeks to help the core member (the person who has harmed others sexually and who is at high risk of doing so again) develop a meaningful life that will be nourishing and not involve harming others. Depending on the core member, that meaningful life may or may not involve a religious or spiritual component.

A new meta-analytic study commissioned by the American Psychological Association has found that the making of meaning is important to people. The study looked at the impact of adapting therapy to include a client’s particular way of making meaning for his or her life. Therapists who add their client’s way of making meaning to the therapy have better outcomes than therapists who do not. If a therapist who is an atheist has a client who is a practicing Catholic or Muslim, the therapist needs to incorporate the client’s faith into the therapy because it will help the person improve (Worthington, Hook, Davis, & McDaniel, 2011). Paying attention to and respecting a person’s way of making meaning makes a difference.

People follow three different ways or paths to make meaning and feel connected: humanist; spiritual; and religious (H/S/R). First, people who are humanist or secular tend to focus on humanity and human life itself as the source of meaning. Humanists do not feel a need to derive meaning from a relationship with a transcendent being or something beyond human life. Second, people who are spiritual, on the other hand, tend to derive meaning from some sense of a transcendent divinity or source beyond human life such as a “higher power.” People who consider themselves spiritual may say they have faith, but they are not involved in organized religion. Third, people who are spiritual and belong to one of the many religious traditions relate to God or the divine through both their particular faith tradition and their own individual spirituality.

In the modern secular age and secular democracies, all three ways of making meaning are common and add value to the diversity of human life. Each path is a legitimate way to making meaning. In the past, the only real option for people was a religious way of making meaning. Throughout most of history, society lived in a religious context; however, in the last 200 years or so other, humanist and spiritual approaches to life have emerged in society (Taylor, 2007).

Within the American Psychological Association, it is now considered an evidence-based practice for therapists to incorporate their clients’ particular H/S/R way of making meaning into their therapy (Norcross & Wampold, 2011). In correctional terms, this is known as the evidence-based principle called “responsivity,” which says that programs should be delivered in a cognitive-behavioral manner and should match or respond to the particular characteristics of each person (Bonta & Andrews, 2010). A person’s way of making meaning is an important characteristic for correctional treatment and programs to take into account.

The Supreme Court has consistently ruled in favor of inmates retaining their First Amendment constitutional right to practice their religious beliefs and way of life. These rights extend beyond spirituality and religion to humanism. In 2005, the U.S. Court of Appeals decided that atheism is a way of life (not a religion) and as such was entitled to the same protections as religion under the First Amendment. Because of this ruling, a prison in Wisconsin had to allow an inmate to form a study group for atheists in the same way they allowed inmates to form religious study groups (Kaufmann vs. McCaughtry, 2005).

According to people like Shadd Maruna (2001) and Fergus McNeil (2006), the process of desistance— lifting oneself out of crime—essentially belongs to offenders. Our job as personnel in the criminal justice system is to support and foster that desistance process. Most offenders will lift themselves out of crime over time, but they will do so more quickly with the right kind of support. For example, Caspi and Moffitt (1995) claim that “the majority of criminal offenders are teenagers; by the early 20s, the number of active offenders decreases by over 50%; by age 28 almost 85% of former delinquents desist from offending.” Part of providing the right kind of support is to work with offenders in a way that helps them build and use what they already possess—their way of making meaning. Helping offenders to express and grow in their way of making meaning is a compassionate, effective, and not very costly approach to reducing recidivism.

H/S/R in a Correctional Context

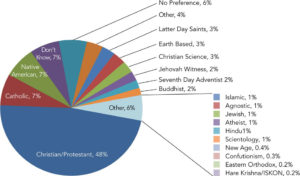

Jail and prison chaplains, often with the help of volunteers, are usually the people responsible for organizing and facilitating the H/S/R services and programs in jails and prisons. A study of prison chaplains and volunteers in Oregon found that most of the services and events they organized were religious or spiritual in nature. Increasingly, however, some of the services take place in a humanist context such as nonviolent communication groups, social study groups, victim-offender dialogues, restorative justice programs, educational programs, and secular meditation programs such as Transcendental Meditation. These humanist-type services work for people of all and no faith traditions. Prison and jail chaplains and volunteers also do a great deal of direct counseling and death/grief support with inmates who do not have any religious or spiritual background or practice. Figure 1 shows this H/S/R diversity for a group of 998 men and women entering the Oregon prison system in 2004 (O’Connor & Duncan, 2011).

Figure 2 shows how women and men entering the Oregon prison system answer a question about how often they had attended a church, synagogue, mosque, sweat lodge, etc., as a child, as a teenager, in the year prior to their arrest, and in the year following their arrest. We see a similar pattern of answers for both men and women: high levels of attendance as a youth, with falling levels of attendance up to the point of arrest, and then a dramatic increase in attendance following arrest (O’Connor & Duncan, 2011). The pattern is even more pronounced for women than for men. Before arrest, the men and women tend to have chaotic, out-of-control lives. However, after they experience the shock of arrest and are in jail, they have more structure and their lives become less chaotic. The arrest stops the downward spiral.

Incarcerated individuals have three meals a day and are separated from previous dysfunctional and violent relationships and from drug and alcohol abuse. In this context, the normal questions of a meaningful life emerge once again. In many ways, the jail is the perfect place for chaplains and volunteers to help people explore a new way of making meaning in their lives—a way that does not involve crime, violence, dysfunctional relationships, and substance abuse. This can be the start of new path of meaning in life.

The H/S/R needs of inmates are so diverse and widespread that prison and jail chaplains must rely on huge numbers of volunteers from different traditions to help the inmates awaken, deepen, and express their particular way of making meaning in life. A recent study of more than 2,000 people who actively volunteer with the Oregon Department of Corrections found that each volunteer gives an average of nine hours of service each month in the prisons or in reentry work, and six hours of prep time each month for this service. In total, their volunteers give 404,199 hours of service each year, equaling 194 full-time staff hours. It would cost the department $13.2 million to hire 194 full-time staff. On top of that, their volunteers drive almost 5 million miles each year to do their volunteer work—at a cost of $2.6 million that they contribute themselves (O’Connor, Lehr, Lazzari, & Duncan, 2011).

Approximately 47 percent of Oregon volunteers consider themselves to be primarily “religious” volunteers. They come from a wide variety of faith traditions such as Jewish, Protestant, Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, Seventh-Day Adventist, Latter-Day Saints, Jehovah’s Witness, and earth-based or pagan religions such as Wicca. Thirty-two percent of the volunteers consider themselves to be primarily “spiritual” volunteers. These volunteers are more likely to belong to groups like Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous or be Native Americans, Wiccans, and Buddhists, who prefer to think of themselves as spiritual but not religious per se. The final 22 percent of volunteers are identified primarily as “humanist” volunteers who tend to offer services in a wide variety of secular contexts such as high school and college education, cultural clubs, communication skills, meditation skills, recreational activities, life-skills development, and administrative tasks in the department (O’Connor et al., 2011).

Figure 3 shows the cumulative attendance rates at H/S/R services for men and women during their first year in the Oregon prison system. It is remarkable that by the third month, 91 percent of the women had attended at least one H/S/R service, and by the end of the year, this increased to 95 percent of the women. Most of the men could not attend any H/S/R event during their first month in prison because they were at an intake center with no H/S/R services. By the third month, however, 49 percent of the men had attended at least one H/S/R event, and 71 percent had attended by the end of the year— also a very high rate of attendance (O’Connor & Duncan, 2011). The higher attendance rate among women mirrors a higher H/S/R attendance level and interest among women in the general population. In more than 49 countries around the world, studies have identified a pattern of significantly higher interest in religion, spirituality, and active ways of making meaning among women as compared to men (Stark, 2002).

Do H/S/R Paths Make a Difference?

Do we have any evidence that this kind of prison/jail involvement in H/S/R paths makes a difference? Several studies have found that the religious practice of prisoners helped them adjust psychologically to prison life in a healthy way (Clear et al., 1992; Clear & Sumter, 2002).

Religious/spiritual involvement helped prisoners manage guilt and find motivation, direction, peace of mind, and meaning in life, as well as hope for the future and support to make a shift in their lifestyle and behaviors (Dammer, 1992, 2002). High levels of religious practice and belief in a transcendent being were also related to less arrest upon release (Sumter, 1999). Clear, Hardyman, Stout, Lucken, and Dammer (2000) argue that a key role of religion and spirituality in prison (and jail) is to prevent, or at least ameliorate, the process of dehumanization that prison and jail contexts tend to foster. Religion and spirituality in corrections help humanize a dehumanizing situation by helping prisoners cope with being a social outcast in a context that is fraught with loss, deprivation, and survival challenges (Clear et al., 2000). Cullen and colleagues argue that criminologists must increase their willingness to help discover and support ways in which correctional institutions can be administered more humanely and effectively (Cullen, Sundt, & Wozniac, 2000). In other words, the practice of H/S/R creates a more compassionate environment for corrections, and people can grow more humane instead of deteriorating in such an environment.

Some studies have found that the practice of spirituality and religion in a prison or reentry context can reduce in-prison infractions and recidivism. O’Connor and colleagues, for example, found that participation in the Transition of Prisoners (TOP) program (www. topinc.net/), originally created by Prison Fellowship, significantly reduced the number of walk-aways or escapes from a pre-release prison in Detroit (O’Connor, Su, Ryan, Parikh, & Alexander, 1997). A later study of the TOP faith-based reentry program found that the program also reduced the recidivism of its participants (Wilson, Wilson, Drummond, & Kelso, 2005). A study by the Federal Bureau of Prisons found that participation in a multifaith prison program reduced in-prison infractions, and a new study is currently examining whether this participation also reduced recidivism (Camp, 2008). O’Connor and Perreyclear (2002) found that religious participation in a South Carolina prison also reduced in-prison infractions.

A study of 16,420 offenders released from Minnesota prisons between 2003 and 2007 found that prison visits from siblings, in-laws, fathers, and clergy significantly reduced recidivism. The authors of the study recommended that prisons and jails become more “visitor friendly” and made the following important but simple point: “considering the impact visits from clergy and, to a lesser extent, mentors appear to have on reoffending, it may be beneficial for visitation programs to focus on facilitating visits from clergy, mentors, and other volunteers from the community” (Duwe & Clark, 2011).

I am currently working as a volunteer to support “Alan,” who was released from prison after 26 years of incarceration. Alan became severely depressed—a known side effect of taking an experimental drug that could cure his hepatitis C—and was arrested and jailed for 10 days on a parole violation. Neither his elderly mother nor I were allowed to visit Alan during his crisis. We both incurred hefty charges on our credit cards from the multiple collect phone calls we received. The jail informed us that Alan would be released at 2 a.m., so I made sure I was available to pick him up because his mother could not drive at night.

Although the event was traumatic, we were able to continue to support Alan. Because of his strengths, Alan has returned to work, is doing well, and is increasing his social support network. His parole officer is impressed with his progress and Alan’s depression lifted once he finished the drug treatment. His hepatitis is now undetectable. The jail system effectively cut off Alan from his support during that crisis; however, with a few policy changes he could have held onto his support. Prisons and jails have one $27 solution available to them: they can become more visitor-friendly and thus create a more compassionate, more effective, and less costly criminal justice system. Sometimes the simple things in life make all the difference.

There are also encouraging outcome findings from an evaluation of the “Ready4Work: An Ex-prisoner, Community and Faith Initiative” launched in 2003 by the U.S. Department of Labor and a nonprofit nonpartisan community organization called Public/Private Ventures (Cobbs Fletcher, Sherk, & Jucov, 2009). The Ready4Work program was developed in 11 U.S. cities and served approximately 4,500 moderate- to high-risk predominantly African-American 18- to 34-year-old men released to the community. Six of the lead agencies in six of the cities were faith-based organizations; three were secular nonprofit agencies, one was a mayor’s office, and one was a for-profit entity. Ready4Work services included employment readiness training, job placement, and intensive case management, along with referrals for housing, health care, drug treatment, and other programs. In addition, participants had the chance to become involved with a one-on-one or group mentoring relationship.

Across the 11 sites, half of the participants chose the mentoring component. These participants, compared to those who chose not to have a mentor, did better in terms of program retention, employment, and recidivism. Mentored participants spent an average of 9.7 months in the program compared to 6.6 months for nonmentored participants. Mentored participants were twice as likely to find a job and maintain job stability. Finally, mentored participants were 35 percent less likely to re-offend within one year postrelease, regardless of whether they ever became employed.

Conclusion

For a variety of reasons, including the need for additional high-quality studies, it is fair to say the research is inconclusive regarding whether faith-based approaches and helping people develop meaning plays an important role in lifting people out of crime and reducing recidivism (O’Connor & Duncan, 2008). Yes, we have some studies that show positive outcomes, but other studies failed to find an impact on in-prison infractions or recidivism. We need many more studies into this aspect of the correctional process before we can fully understand the unique role and contribution of H/S/R work to lifting people out of crime and into stable work and satisfying relationships. Forthcoming outcome studies by the Federal Bureau of Prisons and the English and Welsh prison services will help us understand this particular aspect of criminology in much greater depth.

Although it is uncertain that H/S/R engagement is an evidence-based practice in corrections, we can say that it is an evidence-based practice for therapists to include the H/S/R way in their clients’ therapy. We can also say there is ample evidence that establishing meaning making of any kind is part of the process for all offenders who successfully lift themselves out of crime. There are thousands of chaplains, volunteers, jail and prison inmates, and people under community supervision who are actively involved in the pursuit of meaning. It is highly likely that fostering and supporting this community-based pursuit of meaning plays an enormous role in developing $27 solutions that will create a more compassionate, more effective, and less costly criminal justice system.

Original Article:

O’Connor, Thomas P. (2012). “$27 Dollar Solutions for Lifting People Out of Crime.” American Jail Magazine, July-August 2012, pp. 8-16.

About the Author

Thomas P. O’Connor, Ph.D., is CEO of Transforming Corrections and teaches Criminology at Western Oregon University. He has worked in corrections for 22 years, most recently as a research manager and as head chaplain for 10 years with the Oregon Department of Corrections. Dr. O’Connor publishes, trains, and coaches widely on implementing evidence-based practices in corrections. He can be contacted at oconnortom@aol.com.

References

Aos, S., Miller, M., & Drake, E. (2006). Evidence-based adult corrections programs: What works and what does not. Olympia, WA: Washington State Institute for Public Policy. Retrieved from http://www.wsipp.wa.gov/rptfiles/06-01-1201.pdf

Bonta, J., & Andrews, D. (2010). Viewing offender assessment and rehabilitation through the lens of the risk-needs-responsivity model. In F. McNeill, P. Rayner & C. Trotter (Eds.), Offender supervision: New directions in theory, research and practice (pp. 19–40). New York, NY: Willan Publishing.

Brooks, D. (2012). Flood the zone. New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/07/opinion/brooks-flood-the-zone.html

Camp, S. (2008). The effect of faith program participation on prison misconduct: The life connections program. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 389–395.

Caspi, A., & Moffitt, T. E. (1995). The continuity of maladaptive behavior: From description to understanding in the study of antisocial behavior. In D. J. Cohen (Ed.), Manual of developmental psychology (pp. 472–551). New York, NY: Wiley.

Clear, T. R., Hardyman, P. L., Stout, B., Lucken, K., & Dammer, H. R. (2000). The value of religion in prison: An inmate perspective. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 16(1), 53–74.

Clear, T. R., Stout, B. D., Dammer, H., Kelly, L., Hardyman, P., & Shapiro, C. (1992). Prisoners, prisons, and religion: Final report. Newark, NJ: School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University.

Clear, T. R., & Sumter, M. T. (2002). Prisoners, prison, and religion: Religion and adjustment to prison. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 12–159.

Cobbs Fletcher, R., Sherk, J., & Jucov, L. (2009). Mentoring former prisoners: A guide for reentry programs. Philadelphia PA: Public/Private Ventures.

Cullen, F. T., Sundt, J. L., & Wozniac, J. (2000). The virtuous prison: Toward a restorative rehabilitation. In H. Pontell & D. Shichor (Eds.), Comtemporary issues in crime and justice: Essays in honor of Gilbert Geis. Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Dammer, H. R. (1992). Piety in prison: An ethnography of religion in the correctional environment. Unpublished Ph.D. diss., Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, Newark, NJ.

Dammer, H. R. (2002). The reasons for religious involvement in the correctional environment. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 35–58.

Duwe, G., & Clark, V. (2011). Blessed be the social tie that binds: The effects of prison visitation on offender recidivism. Criminal Justice Policy Review, 22(4).

Kaufmann vs. McCaughtry (U.S. Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit 2005).

Maruna, S. (2001). Making good: How ex-convicts reform and rebuild their lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

McNeil, F. (2006). A desistance paradigm for offender management. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 6(1), 39–62.

Norcross, J. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2011). What works for whom: Tailoring psychotherapy to the person. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67, 127–132.

O’Connor, T., & Bogue, B. (2010). Collaborating with the community, trained volunteers and faith traditions: Building social capital and making meaning to support desistance. In F. McNeill, P. Rayner, & C. Trotter (Eds.), Offender supervision: New directions in theory, research and practice (pp. 301–322). New York, NY: Willan Publishing.

O’Connor, T. P., & Duncan, J. B. (2008). Religion and prison programming: The role, impact, and future direction of faith in correctional systems. Offender Programs Report, 11(6), 81–96.

O’Connor, T. P., & Duncan, J. B. (2011). The sociology of humanist, spiritual, and religious practice in prison: Supporting responsivity and desistance from crime. Religions, 2(4), 590–610.

O’Connor, T., Lehr, J., Lazzari, S., & Duncan, J. (2011). Prison and re-entry volunteers: An overlooked, creative and cost effective source of human capital for desistance. Paper presented at the American Society of Criminology, November 2011, Washington, DC.

O’Connor, T. P., & Perreyclear, M. (2002). Prison religion in action and its influence on offender rehabilitation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 11–33.

O’Connor, T., Su, Y., Ryan, P., Parikh, C., & Alexander, E. (1997). Detroit transition of prisoners: Final evaluation report. Silver Spring, MD: Center for Social Research.

Stark, R. (2002). Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender differences in religious committment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(3), 495–507.

Sumter, M. T. (1999). Religiousness and post-release community adjustment. Unpublished Dissertation, Florida State University, Tallahassee.

Taylor, C. (2007). A secular age. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wilson, L. C., Wilson, C., Drummond, S. R., & Kelso, K. (2005). Promising effects on the reduction of criminal recidivism: An evaluation of the Detroit transition of prisoner’s faith based initiative.

Wilson, R. J., Cortoni, F., & McWhinnie, A. J. (2009). Circles of support & accountability: A Canadian national replication of outcome findings. Sexual Abuse: A Journal of Research and Treatment, 21(4), 412–430. Unpublished study.

Wilson, R. J., Picheca, J. E., & Prinzo, M. (2007). Evaluating the effectiveness of professionally facilitated volunteerism in the community-based management of high-risk sexual offenders: Part two—a comparison of recidivism rates. The Howard Journal, 46(4), 327–337.

Worthington, E. L., Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., & McDaniel, M. A. (2011). Religion and spirituality. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(2), 204–214.