Collaborating with the Community, Trained Volunteers and Faith Traditions

O’Connor, T & Bogue, B., Collaborating with the Community, Trained Volunteers and Faith Traditions; Building Social Capacity and Making Meaning to Support Desistence, October, 2010 in McNeill, Fergus., Rayner, Peter. & Trotter, Chris. (Eds.) Offender Supervision: New Directions in Theory, Research and Practice. Willan Publishing Ltd.

Offender Supervision of randomized controlled trials’, Archives of Disease in Childhood, 86 (4): 251-56. Wright, K.N. and Wright, K.E. (1992) ‘Does getting married reduce the likelihood of criminality? A review of the literature’, Federal Probation, 56 (3): 50-6.

Chapter 15

Collaborating with the community, trained volunteers and faith traditions: building social capacity and making meaning to support desistance

Tom O’Connor and Brad Bogue

Introduction

This chapter tells a story about volunteers, community organisations and faith traditions working alongside probation and parole officers to support men and women in their desistance process. There are dangers in telling this story because everywhere you turn there are concerns -and conflicting viewpoints about our topic. Some probation and parole officers are afraid to work with volunteers for reasons of safety; ‘volunteers mean well but our clients will manipulate them’. Other officers are wary for reasons of professionalism; ‘volunteers want to help but they do not know what thy are doing’. Yet, other officers are embracing volunteers and religious ‘we could not do our work without them!’ Our topic also ILends to raise concerns about the separation of religion and state. We realise that different countries, such as France and the US, take very cliff’ erent approaches to the separation of religion and state. The histories of volunteerism ti and faith group involvement in corrections also differ markedly from country to country: We are confident that a synthesis is possible that reconciles these legitimate. concerns and conflicting viewpoints. We open with an account of a faith-informed volUnteer programme that we believe has achieved dramatic success.

The COSA story

The story begins in Hamilton, Canada in 1994. Reverend Harry Nigh, the pastor of an inner-city ministry, receives a call from a prison psychologist asking for his help. The prison psychologist is working with a man, let’s call him Tim, who is about to be released from prison. Tim is a high profile sex offender. Tim is assessed as having an extremely high risk of recidivism, and he has no support in the community to assist with his re-entry. Tim, however, has identified Pastor Nigh to the prison psychologist as potential support. Tim had built a friendship with the Pastor almost ten years earlier during a prison visitation programme. Because of his notoriety, news of Tim’s release has generated a great deal of media response, as well as community outrage, protest and anger. It is obvious to Harry that the fears and response of the community to Tim’s release are exacerbating Tim’s re-entry needs.

Despite the difficult circumstances, Harry agrees to offer Tim support. Because of the dangerous and serious nature of the case, however, Harry also asks several others from his faith community to help him. Harry also approaches a concerned community member from the local Neighbourhood Watch. The woman from the Neighbourhood Watch group agrees to join the group to ensure that any support given to Tim will be responsible and lead to greater community safety. To make a long story short, Tim and the volunteers went on to develop a network of working relationships, support strategies and friendships that was integral to Tim’s successful desistance journey. Tim created a new life for himself and remained crime free for the 12 years of life he had remaining to him.

Around the same time that Tim was released, a friend of Harry’s, a prison chaplain called Hugh Kierkegaard, also recruited a group of church-based volunteers to support another high risk releasing sex offender in Toronto. Harry and Hugh began to speak a lot about their experiences and collaborate with the Mennonite community and other friends who had training and experience in restorative justice. This collaboration gave birth to COSA, or Circles of Support and Accountability. COSA is a cooperative movement between community-based organisations, faith-informed volunteers and the Chaplaincy Services Division of Correctional Service Canada (the Federal prison system in Canada).

The Washington State Institute of Public Policy (WSIPP) included an evaluation of COSA in its 2006 meta-analysis of 291 rigorous research studies called ‘Evidence Based Adult Corrections Programs: What Works and What Does Not’. The COSA study (Wilson et-al. 2005) met the methodological standards for quality research and inclusion in the meta-analysis. The meta-analysis found that the COSA programme had the largest reduction of recidivism (31.6 per cent) and the largest effect size (—.388) among all of the 291 studies (Aos et al. 2006).

COSA circles, of four to seven trained volunteers and a core member (the high risk sex offender is called the core member), now operate across Canada and internationally in countries such as England and Wales. To be part of a COSA circle, volunteers must attend a lot of training and the COSA local project coordinator, a paid member of staff who conducts the training, must also feel that each person will make a suitable COSA volunteer (Correctional Service of Canada 2002). Not only are COSA volunteers well trained, but they are professionally supported and they work in conjunction with public institutions such as community agencies, treatment providers, parole and probation officers, police and the courts.

Evaluations of COSA have also found that members of the community are more willing to accept the of a high risk and high need sex offender in their community if they- knows that he or she is involved with a COSA circle (Wilson et al. 2007). The Canadian government has recently allocated an additional $8 million of funding to the prison chaplaincy division and its community partners to further expand and develop COSA. COSA, therefore, helps to meet a pressing need in the community to keep people safe and help members of the public address d ieir fears about high risk sex. offenders returning to the community.

A new national replication of outcome findings has found that the original COSA findings do not appear o be site specific. Across Canada, offenders in COSA had an 83 per cent reduction in sexual recidivism, a 73 per cent reduction in all types of violent recidivism and an overall reduction of 71 per cent iri all types of recidivism as compared to the matched offender control group. The new study concludes that its findings ‘provide further evidence for the position that trained and guided community volunteers can and do assist in markedly improving offenders’ chances for successful reintegration’ (Wilson et al. 2009).

What if more community members were to respond as Harry Nigh did to requests for help from probation or parole officers in their local community? What if probation and parole systems were able to work more effectively and efficiently with the Harry Nighs of their community? What if each community Iliad an organised system for training and guiding community volunteers to support and hold accountable the many men and women who need support as they live out their own unique story of desistance?

The integrated model for corrections

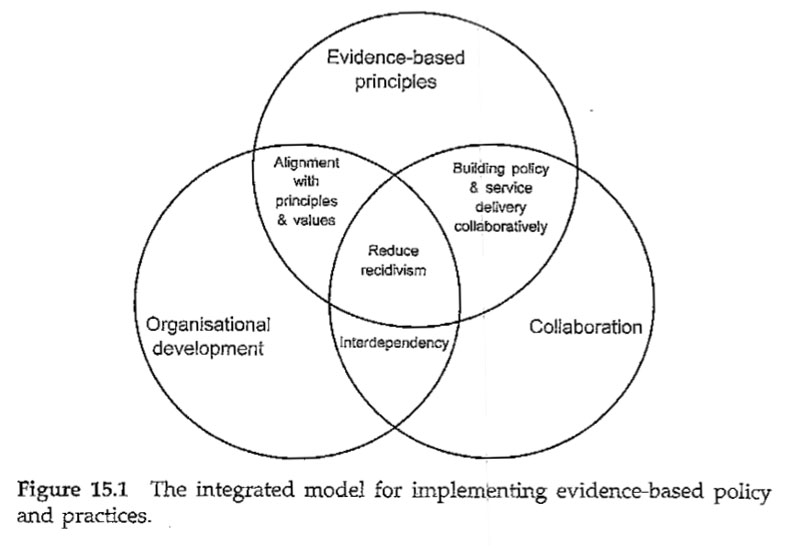

Implementing volunteer and community development systems would mean taking seriously the third circle of the integrated model for Implementing Evidence-based Policy and Practice in Community Corrections by the Crime and Justice Institute and the US National Institute of Corrections (2009). Put simply, the model posits that there are three interdependent dimensions (see Figure 15.1) to implementing evidence-based policies and practices in community supervision. Each dimension must be given equal value. Agencies that do not work on all three levels fail to become evidence-based.

The first element is to undergo a process of organisational development. This process is necessary before an agency can fully move from traditional to evidence-based forms of supervision. The second component is using evidence-based principles and practices of supervision with fidelity to their own original design. The third is entering into collaboration with community stakeholders. This collaboration enhances internal and external buy-in and creates more holistic system change. The first and second components are internal strategies. The third component is an external strategy and requires correctional agencies to share decision-making with their various partners. But shared decision-making does not come easily or naturally to an organisation that is built on the concept of formal social control and power over others (Crime and Justice Institute 2009).

Why is the third circle so necessary and important? Doing the kind of work we do without the third circle is like asking ourselves to run a marathon on one leg with no prosthesis. The complexity, nuance, and scope of our job — to increase public safety and help lift large numbers of people out of crime — is simply beyond the reach of any internal correctional strategy. Self-enclosed correctional agencies, by definition, can never discover the insights and knowledge necessary to prevent themselves from going around in self-perpetuating circles that remind one of the tragic silent comedy in which the Keystone Kops forever chase but never catch the robbers. We need the external resources of the third circle to bolster the work we currently do. We alk) need the new possibilities for safety and goodness made available to us through collaboration with I external groups. We need to remember that authentic cooperation is the source of legitimate power (Lonergan 1972). Corrections can cooperate with the community and establish interdependent relationships that respect the autonomy, unique role, resources and skill sets of both partners. Doing so will greatly enhance our legitimacy in the eyes of the public and the offenders we serve.

Collaborating with external resources

Large numbers of community correctional agencies are now experimenting with a variety of forms of community engagement. Mentoring is one form of such collaboration that can bring a huge amount of resources to the table. There are .many groups, such as veterans, people in recovery, ex-offenders and business people, who might be willing to contribute to their community through mentoring. There is some research to show that carefully structured and well run mentoring programmes for young people at risk can help to bring about social, behavioural and academic change. These youth mentoring programmes work because the mentors are able to develop a trusting relationship with the young person and provide consistent, non-judgemental support and guidance (Sipe 1996, Tierney et al. 2000). We know less about the impact of mentoring with adults, especially adult ex-prisoners. An evaluation of a peer support/mentoring programme called ‘Routes Out of Prison’ in Scotland sheds a lot of light on the difficulties of working with people coming out of prison who have multiple and complex needs (Schinkel et at. 2009). About 40 per cent of the 1,226 men and women (average sign up each year) who signed up for the Routes Out of Prison programme each year in four prisons went on to engage with the programme in the community. The peer mentors (people who had experience with offending, substance abuse or living in areas of multiple deprivation) were able to establish supportive coaching relationships with these men and women and help bridge about 30 per cent of them to employment or training outcomes or connect them with service agencies (Schinkel et al. 2009).

There are, also encouraging outcome findings from an evaluation of the ‘Ready4Work: An Ex-prisoner, Community and Faith Initiative’ launched in 2003 by the US Department of Labor and a non-profit, non-partisan community organisation called Public/Private Ventures (Cobbs Fletcher et at. 2009: 3). The Ready4Work programme took place in 11 US cities. The programme served approximately 4,500 moderate to high risk, predominantly African-American 18- to 34-year-old men released into the community. The men had served non-violent felony sentences, and most of them had prior criminal histories and incarcerations. Six of the lead agencies in six of the cities were faith-based organisations, three were secular non-profit agencies, one was a mayor’s office and one a for-profit entity. Ready4Work services included employment readiness training, job placement and intensive case management, along with referrals for housing, healthcare, drug treatment and other programmes. In addition, participants had the chance to become involved with a one-on-one or group mentoring relationship.

Across the 11 sites, about half of the participants chose the mentoring component. These participants, compared to those who chose not to have a mentor, did better in terms of programme retention, employment and recidivism. Mentored participants spent an average of 9.7 months in the programme compared to 6.6 months for non-mentored participants. Mentored participants were twice as likely to find a job. Comparing those who found a job, people with a mentor were more likely to meet the three-month job retention benchmark for job stability. Finally, mentored participants were 35 per cent less likely to reoffend within one year post-release, regardless of whether they ever became employed. Cobbs Fletcher et al. (2009) point out that there was no control group in this evaluation. The study merely compared those who volunteered to work with a mentor to those who did not volunteer. The self-selection or I motivation factor could therefore account for the differences in outcomes. Discrepancies in programme quality and structure across fir sites May also have played a role in whether or not participant engaged in mentoring. For both of these reasons the findings are not conclusive but they do suggest that mentoring with men and women under community supervision may play an important role in helping them to stay in a programme, find a job, stay employed, and stay out of trouble (Cobbs Fletcher et al. 2009: 3-4). An external strategy brings much-needed resources to our table. Engagement with these resources can also help provide the spark and momentum we need to change and improve our own internal practices.

Collaborating with external perspectives

The external strategy allows corrections to interact with and benefit from positive cultural forces as well as new ideas and perspectives from other disciplines. Charles Taylor, the Canadian philosopher, has shown how historical forces and trends in the West, such as the Enlightenment, the establishment of secular democracies, the growth and dominance of rational, instrumental and scientific methods of thinking and the emergence of individualism, have resulted in a broad-based western culture that places a high value on each person’s search for authenticity.

We live in a world where people have a right to choose for themselves their own pattern of life, to decide in conscience what convictions to espouse, to determine the shape of their lives in a whole host of ways that our ancestors couldn’t control. And these rights are generally defended by our legal systems. In principle, people are no longer sacrificed to the demands of supposedly sacred orders that transcend them. (Taylor 1991: 2)

Most people today give assent to what Taylor calls the ‘ethics of authenticity’. Our culture expects each person to find, express and be faithful to their authentic or true self as they try things out, learn from their mistakes, grow in experience and mature. We highly regard people whom we consider to be authentic ink their way of being and expressing themselves in the world.

How does this western story or way of thinking about authenticity play out in corrections? Unfortunately, the recognition that we all can and must continually strive for authenticity seems to have little to do with corrections. Society, in large part, denies this recognition to criminals, inmates, probationers, parolees and ex-offenders. Somehow ‘offenders’ forfeit what Taylor refers to as ‘the moral force of the ideal of authenticity’. In general, on a moral, social and legal level, society tends to forever remain suspicious of inmates and offenders even when they manage to turn their lives around. In the US one out of every 40 voting age adults, or 5.4 million Americans, have permanently lost their right to vote because of a felony conviction. The vast majority of these people are no longer in prison. In several states one in four black men can no longer vote (Manza and Uggen 2006). Looking at the headlines of a Canadian newspaper that covered the release of a COSA core member, we can see how these headlines support values of ostracism, banishment, violence and fear while also denying the possibility of any growth into authenticity for the core member:

- Pery Out Of Jail Today: Police Consider Publishing His New Address

- Pervert A Risk

- Pedophile ‘Terrified’ To Be Out Of Jail

- A Community Lives In Fear

- Perv’s Neighbors In Scary, Ugly Mood

- Neighbors Drive Pery From Home

- Molester, 24-Hour Ultimatum

- Neighbors: We’ve Done Our Jobs

By contrast, the language used by COSA to express its core values is very different. Notice how the COSA language recognises and seeks to support victims, while the newspaper language pays no attention to those who have been victimised.

- We affirm that the community bears a responsibility for the safe restoration and healing of victims as well as the safe re-entry of released sex offenders into the community

- We believe in a loving and reconciling Creator who calls us to be agents in the work of healing.

- We acknowledge the ongoing pain and need for healing among victims and survivors of sexual abuse and sexual assault.

- We seek to ‘re-create community’ former offenders in responsible, safe, healthy and life-giving ways.

- We accept the challenge of radical hospitality, sharing our lives with one another in community and taking risks in the service of love.

The language of the newspaper is a language of condemnation, hopelessness, separation and violence that seeks to silence and bring an end to a painful story. The COSA language is a language of accountability, service, redemption, collaboration and transformation. The COSA language seeks to foster and keep a story of resilience, healing, the overcoming of betrayal and desistance alive. Ultimately, one language disempowers and creates a dependent person upon whom the criminal justice system acts. The other language empowers and creates agency and interdependent collaboration. Disturbingly, our work takes place in a social context where the disempowering language is generally treated by many in the media and politics as the dominant public language. This is so even though public opinion is much more discriminating and diverse in its attitudes towards crime and punishment (Peter D. Hart Research Associates 2002; Green 2006).

The dominance of this language of condemnation has a profoundly negative effect on every person who works in the field of probation and parole, and on every offend, because it limits our true potentialities and tends to create co-dependency, frustration and failure. The language of condemnation reinforces a Keystone Kops mentality: What is the dominant language within your particular correctional cultures? To what extent is it a language of condemnation or transformation? Speaking for our (the authors) correctional settings we often hear the language of condemnation and seldom the language of transformation.

Alongside the languages of condemnation and transformation we also hear a language of control and punishment through the loss of freedom accompanied by a language of instrumental reasoning which would have us use evidence-based practices and the principles of risk, need and responsivity to increase public safety We know that such instrumental or programmatic reasoning, when put into practice with fidelity, results in very positive public safety outcomes; on average a 28 per cent reduction in recidivism (Smith et al. 2009). We also know that there is another, less dominant, language our field. This is the language of ‘desistance’, which differs in tone and substance from the language of instrumental reasoning and effective programming. The language around the desistance process is about personal stories of agency, interdependence, maturation and striving for authenticity.

To be humane and effective we need both our language of instrumental reasoning and our language of desistance. But we also need the community language that comes from external sources such as COSA. The field of corrections has everything to gain by expanding its collaboration with community groups like COSA. Such collaboration enables us to work, think and imagine in the context of different social languages and cultural norms that are more supportive of both our instrumental and desistance languages. It is not by accident that Shadd Maruna advanced our appreciation and understanding of desistance by going out into the community and attending to the true life stories and narratives of career criminals in Liverpool (Maruna 2001). The language of instrumental reasoning and effective programming concerns an internal strategy that is under our control. This language carries its own inherent strengths in terms of creating the conditions for a certain understanding and knowledge, but it also carries its own inherent weaknesses that render it almost incapable of discovering and exploring phenomena such as COSA or desistance. We need a constellation of languages so that we can better imagine, create and support meaning out of the harsh, complex and paradoxical realities of crime, victimisation, suffering, failure, loss of freedom, resilience, recovery, and change that we work with on a daily basis.

A community development approach

Some probation and parole officers are adept at helping their clients to make effective use of community resources. Over the years these officers build up a set of great relationships with the treatment, employment, housing, family, informal social support groups and other resources in the community. John Augustus, the founder of Probation, also knew that creating linkages between his clients and community resources was crucial. Indeed, making effective use of community resources forms one of the five research-supported, core correctional practices for staff (Dowden and Andrews 2004). Today, however, there are so many people under supervision with so many needs, that officers cannot possibly rely solely on an individual approach. We are overwhelmed by our client numbers. So it is better to take a community development rather than an individual offender focus when we consider a collaboration strategy with the community.

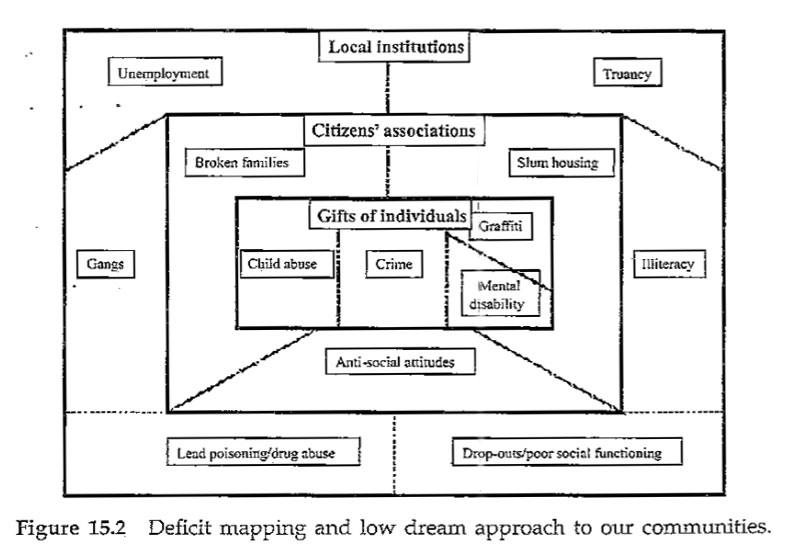

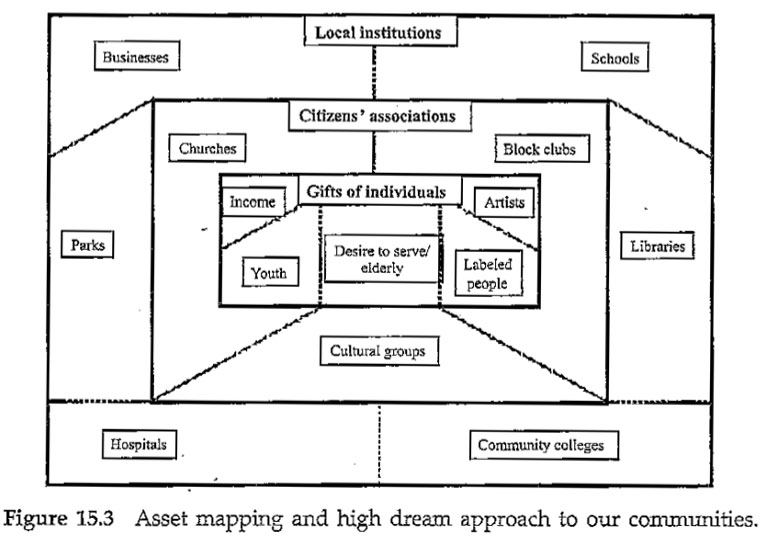

Our job is to partner with the community, build up the social capital of the community, and render it more capable of supporting desistance for particular offenders. We have learned how to focus on and strengthen the protective factors for clients. Now we must learn how to focus on arid strengthen protective factors in our communities. This means taking an asset-based approach to community development (Kretzman and McKnight 1993). Kretzmann and McKnight show two maps for a single community that bring the value of an asset-based model for community development into sharp relief. The two maps compare the conventional sensationalised media and political perspective that portrays all of the community’s needs, deficits and problems (Figure 152) with an alternative view that focuses on the positive elements and widespread potential of the community (Figure 15.3).

The point of view represented in Figure 15.2 is realistic. In most communities, where there is a lot of crime, it is easy to point to the presence of high levels of drug abuse, unemployment, truancy, gangs, crime and anti-social attitudes. These are just a few of the negatives that make living in a high crime neighbourhood a risk factor in many of our risk and needs assessments. We call this approach, which always leads with the problems or the bad news, the ‘low dream’ approach.

But it’s also possible to take what we call it ‘high dream’ approach to our work and lead with what is strong and positive about a situation. The high dream approach, for example, would have us focus first on the many people who have been in prison and made positive and even spectacularly positive contributions to society. Think for a moment of the many people you know personally who have done well after doing time in a prison or under community supervision. Although not quite the same, we can also think of Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, Anne Frank, Henry David Thoreau, Malcolm X, St Paul, Aung San Suu Kyi and Nelson Mandela, all of whom were ‘inmates’. We have to find more ways of thinking about and imagining what positive psychology calls ‘positive deviance’ (Cameron 2008) and less about negative deviance. Positive deviance refers to examples of people and organisations who stand out from the normal in the positive direction. A perspective that begins with positive deviance provides an attractive vision that energises our work to bring some good out of the horrors of criminality and prevent further tragedies. We can look at the exact same community, depicted in Figure 15.2, in an entirely more hopeful, realistic and empowering way (Figure 15.3).

Kretzmann and McKnight (1993) point out that even the hardest-hit communities in the poorest neighbourhoods in large cities are filled with resources such as schools, hospitals, libraries, elderly folks with time to give, young people with enthusiasm and energy, businesses, churches, mosques, synagogues, boys’ and girls’ dubs, AA and NA meetings and a whole variety of other pro-social organisations. What tends to happen, however, in these hard-hit communities is that the linkages and patterns of communication between all of these resources become weakened compared to communities that are thriving. The work of community development, therefore, is to strengthen and increase the linkages between these resources. Parole and probation officers can support the desistance process by strengthening the linkages between the positive resources in their communities and connecting these resources to corrections. When one looks upon a community from a deficit perspective, it’s easy to conclude that the community is broken. Thus, the only solution is to pour ‘vast amounts of money and resources into the community from outside the community. The reality, however, is that every community (ari0. offender) has its own internal resources for building itself up, and can do so, especially if it gets the right kind of help. Internally motivated change, supported by external resources, is more likely to succeed than externally motivated change. This is true, both for offenders and communities. This kind of asset-based community development approach shares a great deal in common with a public health model for corrections (US Department of Health and Human Services 2007). Engagement with the ‘outside’ world is crucial to the development of corrections.

Humanistic, spiritual and religious ways of making meaning Religious volunteers tend to be very active in corrections in many countries, and there is a growing body of research on the role, impact and future direction of religion in correctional systems (O’Connor and Duncan 2008). The largest group of volunteers who work with prisons, jails and community corrections seem to be related in some way to religious faith traditions. This seems to be so in many countries, such as Canada, England, the US and Fran. 6. For instance, 1,976 men and women currently volunteer with the Oregon Department of Corrections which has 14 prisons and approximately 14,000 prisoners. Of these volunteers, 75 per cent are ‘religious volunteers’ who come from a wide variety of faith and spiritual traditions such as Native American, Jewish, Protestant, Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, Seventh Day Adventist, Latter Day Saints, Jehovah’s Witness, and Earth-Based or pagan such as Wicca. Another 10 per cent of the volunteers in Oregon work in the area of drug and alcohol recovery, primarily from the Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous (AA and NA) traditions. These AA and NA volunteers tend to fall into a ‘spiritual’ category. They are not ‘religious’ in the sense of belonging to an organised religion. They are generally spiritual, however, because a ‘higher power’ is a core part of their motivation for volunteering and their way of working. Research on the impact of twelve-step type programmes such as AA and NA has increasingly demonstrated reductions in days of drug/alcohol use. Programme involvement, frequency of interaction with others in the recovery affiliation, as well as the ability of these groups to help people shift social networks, seem to be important causal factors for their success (Moos and Moos 2004b; Tonigan 2001; Moos and Moos 2004a; McGrady et al. 2004). The large network of AA and NA groups in almost every community makes these groups natural community partners.

The final 15 per cent of volunteers in. Oregon tend to work out of a wide variety of secular contexts and help with education, cultural dubs, recreational activities, life skills development and administrative tasks in the department. Perhaps a good example of this third group, whom we call secular or humanist in. their orientation and work, would be many of tie people who volunteer in the Inside-Out programme. In 1997 Lori Pompa founded the Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program which is based in Philadelphia at Temple University. Inside-Out trains professors to teach semester-length college-level courses (for example, Introduction to Criminology) inside prisons to about 30 students. Half of the students in the class are incarcerated and half are students from a local university or college. All of the students in the class are expected to participate on an equal level, use only first names, and complete all the course reading and requirements. There are no ‘research findings’ yet about Inside-Out, but there are many stories about students who undergo a process of change and radical awakening in the course of taking a class. Inside-Out has held nearly 200 classes with over 6,000 students, and trained more than 200 instructors from over 100 colleges and universities in 35 US states and Canada. The Inside-Out programme ‘increases opportunities for men and women, inside and outside of prison, to have transformative learning experiences that emphasize collaboration and dialogue, inviting participants to take leadership in addressing crime, justice, and, other issues of social concern’ (www.insideoutcenter.org/home.html).

As we have seen, a large proportion of volunteers who engage with corrections are from religious or spiritual traditions. This means that we have to address separation of religion and state issues. O’Connor et al. (2006) devote a whole paper to the shape of an authentic dialogue between religion and corrections. The authors make one major point about how to have a legally and culturally appropriate engagement between religion and corrections. Our own authenticity, or appropriateness for a government-backed agency such as Connections means that we must engage equally with all of the humanistic, spiritual and religious ways of making meaning that take place among our clients and the communities we partner with. Especially in so far as these ways of making meaning relate to the desistance process.

In his highly acclaimed book A Secular Age, Charles Taylor (2007) gives a fascinating account of what it means to live in our modern secular democracies and a secular age. For Taylor, it means that every person has a choice about how they will create a sense of ultimate meaning for their life. Ultimate meaning usually refers to working with questions about the purpose of life, health, justice, suffering, evil and death. The more traditional choice that derives a sense of meaning from a diverse range of religious and spiritual traditions. All of these different religious and spiritual traditions posit a transcendent source or ground of meaning, usually called God or the Divine. But now we live in a secular age, and there is another choice: to make meaning in a way that makes no reference to God or the Divine, but only to human life and the human condition’. This purely secular, or humanistic, way of making meaning is new. Never before in history has this choice been available on a broad societal level. Nowadays people take this choice for granted (Taylor 2007).

Historical, philosophical, political and cultural forces have established the right of people to follow any faith tradition of their choice without interference from the state. These developments have -also established the right of people ‘not to believe’, or rather, to put their faith and belief in human life. See, for example, the work of Greg M. Epstein, who is a humanist chaplain at Harvard University and author of Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe (2009). State officials who work with and serve the public must be prepared to engage equally with all three ways of making ultimate meaning: humanist, spiritual and religious. For many years professional staff and state employees followed their training and stayed away from questions of religion, spirituality and meaning with their clients. People were fearful of crossing professional and religion/state boundaries, and wanted to respect the autonomy of their clients in matters of faith and religion. The desistance literature, however, has taught us that a particular client’s self narrative or way of making meaning and deriving agency in their life is crucial to their desistance process as they mature, develop social bonds and create a new ‘redemption’ (Maruna 2001). McNeill argues that ‘offender management services need to think of themselves less as providers of -correctional treatment (that belongs to the expert), and more as supporters of desistance processes (that belong to the desister)’ (McNeill 2006: 46) There are three major sources of ultimate meaning that belong to desisters and their communities: humanistic, spiritual and religious.

Probation and parole officers who learn how to support all three sources of meaning among their clients can help support desistance. Probation Sand parole officers are comfortable asking clients about their education, their drug and alcohol use, their families, their criminal histories, and even their sexual histories and fantasies. Probation and parole officers can also learn to become comfortable asking their clients how they make meaning in life. Adapting the work of Puchalslci (1999), we recommend four simple questions as part of the regular process of building rapport with and accessing a client’s risk, need, responsivity and protective factors:

- I wonder if religion or spirituality plays a role in your life or if meaning for you comes more from a human point of view?

- How important is that way of looking at life for you?

- Are you part of any community or group of people that shares your views on life?

- How would you like to bring this part of your life into our work together and your plans for being successful without crime?

Using motivational interviewing approaches and the responsivity principle, officers can discover and support the particular meaning story that is active in each of their clients. One simple way to support this meaning is to help match clients up with the right volunteer and community supports. We know that many of the men and women who are in prison, jails and under community supervision respond in a very positive manner to volunteers from each of the religious, spiritual and humanist milieus. In responsivity terms, different people are open and willing to work with each group of volunteers because they find a match with their own way of being in the world. The more attributes and shared background between the volunteers and the people they support, the stronger the potential for positive social support effects. For example, consider the outreach potential of groups like successful ex-offenders or veterans. There are 12 million veterans in the US alone. Veterans share a number of attributes – majority male, familiar with violence, high prevalence rates of PTSD – with those under community supervision and so can establish empathic working relationships with them. any veterans also bring leadership training and experience, skills for recovering from drugs and alcohol, and pro-social commitments to family, work, education and community. With training, these veterans can appropriately apply all of their skills to a correctional and desistance context. No doubt, veterans also have a diverse mix of humanist; spiritual and religious orientations, and additional matching on these variables will increase the potential for forming legitimate working relationships and positive social support effects that promote desistance.

Creating a volunteer and community development system

The financial costs of collaborating with volunteers and community organisations are small, and the return on investment is potentially large. Volunteers donate an estimated 25,000 hours of service each year to the Oregon Department of Corrections (O’Connor and Duncan 2008). This is the equivalent in hours of 121 full-time staff positions, or over $5 million in value if one uses the Independent Sector (2008) figure of $20.25 per volunteer hour to estimate the value of their services. Three full-time volunteer programme staff members in the department recruit, train, card, manage, thank and assist these volunteers to work with every unit in the department. Staff members in each unit supervise the volunteers and guide their work. So volunteers are inexpensive, but they are not free. It takes dedicated time and skill on the part of staff, to build a system of training and collaboration with them. This is especially so if we expect volunteers to be effective arid safe. Because of their training and natural inclination, professional chaplains, who work out of a variety of humanist, spiritual and religious perspectives, are often excellent at collaborating with community resources and working with and training volunteers (O’Connor et al. 2006). Many prisons currently have professional chaplains on staff, but few, probation and parole agencies do. Perhaps it is time for probation and parole agencies to consider hiring dedicated chaplain staff for creating a volunteer and community development system for their agencies.

In a recent paper we outlined a logic model that combined four different sets of skills for probation and parole officers in their work with people under community supervision. We set out a general framework and strategy for community supervision by articulating what four different sets of literatures have taught us about the evidence-based effectiveness of our work (Bogue et al. 2008). First, general factor research into the central role of an empathic working relationship between an officer (or any change agent) and their client led us to recommend motivational interviewing approaches for officers as they build rapport and evoke motivation for change with their clients. Second, the contingency management literature shows how important it is for officers to be skillful in using rewards and punishments appropriately to reinforce accountability. Third, the cognitive behavioural treatment literature provides officers with a guide for when, and how to refer to cognitive behavioural treatment. This literature also helps officers know how to coach, reinforce and skill train their clients in their new cognitive behaviours such as relapse planning. Fourth, the desistance literature points to the role of officers in supporting social network enhancement for their clients and mobilising community support.

Volunteers have their own sets of skills and unique roles in the correctional process. Volunteers are not miniature probation and parole officers, and we should not try to mould them in this way. However, they are willing and, with training, are able to collaborate with probation and parole officers in a targeted manner that enhances each of the four vital skill sets (above) or approaches to working with offenders. For example, COSA trains its volunteers to support the relapse prevention plans of their core members. AA and NA sponsors are often adept at helping people enhance their social networks. A faith-informed statewide re-entry programme called Home for Good in Oregon trains its volunteers to use motivational interviewing approaches to support moderate and high risk people as they develop pro-social attitudes, values and beliefs and establish a pro-social network of friends and acquaintances (O’Connor et al. 2004), Given such volunteer and community development systems, we are more than willing to concur with the findings of Wilson et al., in the 2009 COSA evaluation: there is ‘evidence for the position that trained and guided community volunteers can and do assist in markedly improving offenders’ chances for successful reintegration’. Corrections can engage and collaborate with the Harry Nighs and their communities in a way that builds social clapacity, makes meaning and supports desistance. Such an external strategy will significantly enhance the ability of corrections to move from. traditional supervision policies and practices and become fully evidence-based.

References

Aos, S., Miller, M. and Drake, E. (2006) Evidence-Based Adult Corrections Programs: What Works and What Does Not. Olympia: Washington State Institute For Public Policy.

Bogue, B., Diebel, J. and O’Connor, T. (2008) ‘Combining officer supervision skills: a new model for increasing success in community corrections’, Perspectives: the Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association, 32: 31-45.

Cameron, K. (2008) Positive Leadership: Strategies for extraordinary Performance. San Francisco: Barrett-Koehler Publishers.

Cobbs Fletcher, R., Sherk, J. and Jucov, L. (2009) Mentoring Former Prisoners: A Guide for Reentry Programs. Philadelphia Public/Private Ventures.

Correctional Service of Canada (2002) Circles of Support and Accountability: A Guide to Training Potential Volunteers. Correctional Service of Canada.

Crime and Justice Institute (2009) Implementing Evidence-Based Policy and Practice in Community Corrections, 2nd edn. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections.

Dowden, C. and Andrews, D.A. (2004) ‘The importance of staff practices in delivering effective correctional treatment a meta-analytic review of core correctional practice’, International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 48: 449-76.

Epstein, G.M. (2009) Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe. New York: HarperCollins.

Green, D.A. (2006) ‘Public opinion versus public judgment about crime: correcting the “comedy of errors”‘, British Journal of Criminology, 46: 131-54.

Independent Sector (2008) Value of Volunteer lime. Online at: www.indepentientsectonorgiprograms/researchivolunteer_time.html (accessed 15 December 2009).

Kretzman, J. and McKnight, J. (1993) Building Communities from the Inside Out: A Path Toward Finding and Mobilizing a Co1mmunity’s Assets. Asset-Based Community Development Institute.

Lonergan, B. (1972) Method in Theology. Minneapolis Seabury Press.

Manza, J. and Uggen, C. (2006) Locked Out: Felon Disenfranchisement and American Democracy. Oxford University Press.

Maruna, S. (2001) Making Good: How Ex-Convicts Reform and Rebuild Their Lives. Washington, DC: Psychological Association.