Combining Officer Supervision Skills

Bogue, B., Diebel, J. & O’Connor, T. (2008) Combining Officer Supervision Skills: A New Model for Increasing Success in Community Corrections. Perspectives: the Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association, 32, 31-45.

Bogue, B., Diebel, J. & O’Connor, T. (2008) Combining Officer Supervision Skills: A New Model for Increasing Success in Community Corrections. Perspectives: the Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association, 32, 31-45.

Bogue, B., Diebel, J. & O’Connor, T. (2008) Combining Officer Supervision; Skills A New Model for Increasing Success in Community Corrections. Perspectives: the Journal of the American Probation and Parole Association, 32, 31-45.

Combining Officer Supervision Skills:

A New Model for Increasing Success in Community Corrections.

John Augustus (1784-1850) gave birth to the entire field of community corrections when he successfully launched the first prototype for the supervision of offenders in the community at the beginning of the nineteenth century.[1]

Almost two hundred years later, however, community corrections lacks a clearly articulated and tested model that can empirically justify and give practical guidance for the daily contact of officers with offenders and the most beneficial allocation of agency resources. Rather, probation and parole systems have gone back and forth between two vague and ill defined officer approaches for reducing recidivism and improving offender outcomes: the so-called law enforcement and case work models.[2]

We argue that both the law enforcement and caseworker approaches have a crucial contribution to make to reducing recidivism. Unfortunately, the positive contributions of both approaches are not clearly articulated or understood and both approaches also contain key elements that contribute to negative outcomes such as increased alienation from society and recidivism. Only a very small number of recently conducted empirical analyses can link offender outcomes to the particular approaches, tasks and skills that officers and agencies use in their daily work.[3-5]

John Augustus’ notes about his work provide us with a glimpse of the underlying model he used to help offenders successfully desist from crime. Many of Augustus’ original strategies such as building a working relationship with offenders, helping them to establish better social networks and using punishments strategically are central elements in community corrections models that increase offender success. If a model for community corrections is to be helpful, it must be meaningful to officers and offenders on an emotional level, easily understood and logical and practical for officers to carry out in the midst of large, challenging caseloads within agencies that are constantly struggling to secure enough resources. Since the 1990’s, the “What Works” research literature has provided our field with an ever deepening understanding of core principles that agencies and officers can use to increase the connections between their work and successful outcomes for offenders.6 These general risk, need and responsivity principles provide some necessary guidelines for the construction of an evidence-based framework for community corrections. However, the principles of risk, need and responsivity do not give officers specific guidance about what to say and do as they meet with offenders on a daily basis. For such guidance, we need to show how these principles can influence officers’ work. We also need to combine the practical implications from the What Works literature with those from other literatures about behavior change to create a model for officers that will be emotionally and intellectually satisfying to them. Such an emotionally intelligent and logical model will concretely describe the causal relationships between officers’ actions and resulting offender outcomes.

Our model for the community supervision of offenders relates the findings from four different bodies of research to the concrete daily work of probation and parole officers. It shows why officers’ work along these lines should lead to the results that most officers, offenders, politicians and members of the community desire: improved safety and quality of life for community members, fewer victims and offenders that become ex-offenders. Finally, it links together four different skill sets that have been tested in research and practice to such a degree that they considered to be “evidence-based practices” (EBP) or strongly associated with EBP for community corrections.

CONSTRUCTING A MODEL FOR OFFICER SUPERVISION FROM FOUR RESEARCH LITERATURES

The field of corrections can now refer to four bodies of evidence or literatures to help determine how field supervision should function if it is to produce sustained and meaningful reductions in recidivism. The four areas of research include:

General Factor research on agent-client relationships;

Contingency Management research on the ways punishments and rewards change behavior;

What Works research on the overall effectiveness of interventions; and

Desistence research on how offenders mature out of crime.

We will begin by summarizing the main findings from these literatures that can help field officers achieve successful supervision outcomes. Then, we will combine the key “take aways” or things to apply from the four literatures into our model for successful supervision strategies.[1]

GENERAL FACTOR RESEARCH AND AGENT-CLIENT RELATIONSHIPS

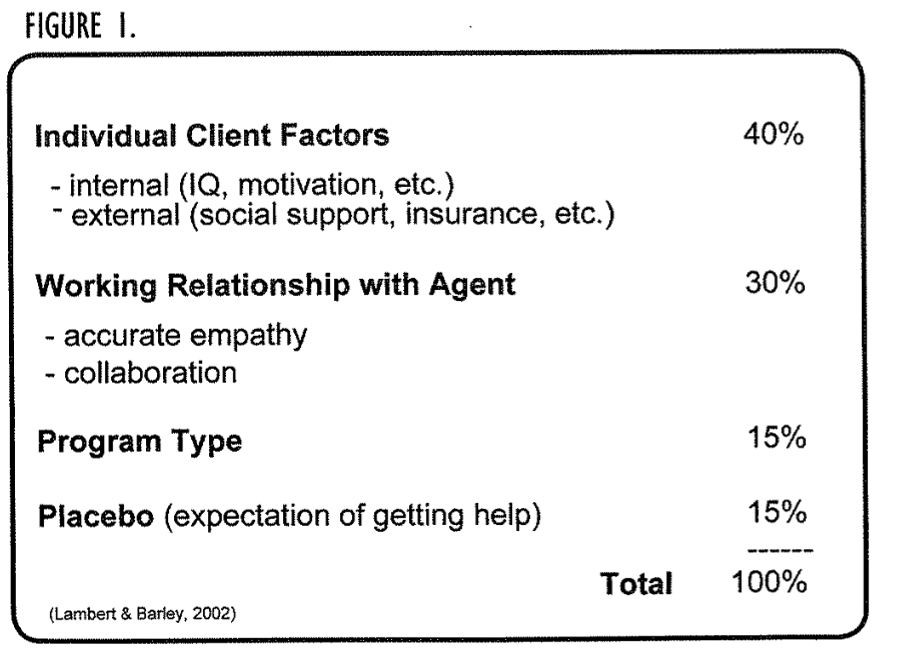

General factor research looks for the mechanisms of change that are common to a whole range of different programs, interventions, modalities and psychological orientations such as substance abuse programs, cognitive programs, employment interventions and the different types of psychological therapies. This research in Figure 1 suggests that the quality of the relationship between the change agents and offenders has twice the impact on positive outcomes (30 percent) as the type of intervention the agents used (15 percent).

In other words, the most important variable under agent control is not the particular kind of intervention they use with their clients, but the quality of the working relationship they have with them. The What Works literature also provides considerable support for this view that relationship-building or working relationships are a key factor6 in fostering offender change.”” The quality of working relationships that probation and parole officers establish with offenders is a variable that can be controlled by community corrections staff and it is not really dependent on procuring significant additional financial resources for the agency. ” Working relationships can begin when staff realize that on average, 40 percent of positive behavior change comes from the offenders internal resources and external support systems. Seeing offenders as potential partners in the change process helps officers to use accurate empathy in interactions with them and keep in mind the goal of creating a working alliance—a relationship in which both people collaborate to establish and negotiate change goals, with a mutual willingness to be flexible and explore a variety of options when necessary to meet those goals and to maintain an effective working relationship.[24, 25] Accurate empathy and a working alliance are key elements of agent-client dynamics that maximize offender potential for positive change.

Moving from general research to specific applications, Motivational Interviewing (MI) provides an approach to agent-client relationship building that has proven extremely successful in 20 years of rigorous research. MI is a counselor-directed, client-centered style of communication that helps people resolve their ambivalence about changing problem behaviors, including alcohol dependence, cocaine addiction, obesity. Officers using this approach engage people in purposeful interactions through reflective listening skills—open questions, affirmations, reflections and summaries—that allow clients do °hear” themselves think and adjust their beliefs and attitudes according to the new clarity that emerges. As people work through their ambivalence, they are more likely to pursue and maintain positive behavior change. Over two hundred randomized clinical trials show that MI produces significant direct effects or benefits for clients, as compared to interventions that to not use MI. A number of quality meta-analyses summarize this research and document the relative effect sizes or impact on clients across different populations.[67-70]

Because of the strength of the General Factor research on the importance of building working relationships with clients and the specific research supporting the use of MI in this process, we recommend MI as the first of four key officer strategies in this new model of Community Corrections.

CONTINGENCY MANAGEMENT RESEARCH AND THE EFFECTIVE USE OF PUNISHMENTS AND REWARDS

According to social learning theory, many human behaviors are instigated, shaped and maintained by the rewards and costs that result either directly or indirectly from behaviors[26][49-56]. A wide array of research literature suggests that human behavior can be effectively shaped or influenced by behavioral reinforcements: the systematic linking of rewards to desired behaviors and punishments to undesired behaviors[49-56]. The law-promoting influence that these kinds of reinforcements have on criminal and non-criminal behavior can be found throughout basic criminology literature.[87-91] What Works literature provides additional empirical support for general and specific applications of reinforcement interventions[26}[92][93] to domestic violence,[94] sex offending,[95] substance abuse[85; 96] and cognitive skill-building.[97-99] The consensus from these literatures is that the delivery of specific systematic reinforcements for select behaviors is successful in shaping outcomes to the degree that each of the following three conditions are met:[57]

- Consistency-the selected behavior is accurately identified and consistently reinforced;

- Immediacy-the selected behavior is reinforced more or less immediately; and

- Magnitude-the reinforcement—either reward or punishment/cost—is sufficiently tangible and meaningful to the person who receives the reinforcement.

Program and intervention approaches that are designed to shift the balance of net rewards and costs for particular behaviors (e.g., drug use, treatment compliance, job searches, community service, restitution, sanctions) through the systematic application of reinforcements or punishments are called Contingency Management programs or CM. Officers can make creative use of the three CM principles – consistency, immediacy and magnitude –as they apply and manage the terms and conditions for their clients. In CM, a specific set of rewards (vouchers, reduced supervision time, etc.) and a specific sec of costs (house arrest, increased breathalyzers, etc.) are made contingent upon specific behavioral performances (submitting clean urines, treatment group adherence, completion of a quota of job interviews, supervision compliance, etc.). While both reinforcement and punishment are typically employed in Contingency Management interventions, staff and clients typically prefer the use of reinforcements.[56]

These interventions have been used with a variety of problem behaviors and treatment compliance issues.[84-86] Clinical trials of these applications have demonstrated such significant reductions in the abuse of opiates,[100-103] cocaine,[104-106] marijuana[107-110] and alcohol[96][111-113] that meta-analyses support the use of CM as an evidence-based practice for substance abuse interventions.[101-103] CM is also effective in improving treatment compliance,[111][115][116] helping people secure employment[17-119] and reducing drug use and violations for correctional populations in drug and other specialty courts.[115][120-122] Because of this strong research support for the use of CM for a variety of problem behaviors,[123] it is the second key supervision strategy in the model.

WHAT WORKS RESEARCH AND THE EFFECTIVENESS OF INTERVENTIONS FOR OFFENDERS

Now including over 40 meta-analyses on offender interventions or rehabilitation programs, the ‘What Works research consistently supports three foundational principles:[4-7]

- The Risk Principle urges officers to apply more intensive treatment and services to higher risk offenders, because this produces a greater overall improvement in recidivism than treating lower risk offenders.

- The Need Principle recommends that agencies focus their interventions on the “central eight” criminogenic need areas for offender rehabilitation because this will improve recidivism outcomes more reliably than focusing on other change targets.

- The Responsivity Principle teaches that offender outcomes are generally improved by Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment (CBT) interventions that focus less on didactic explanation and demonstration, and focus more on skill rehearsals, simulations and role plays to correct the specific skill deficits that lead to criminal behavior.

At first glance, it may seem chat the title of the third principle is at odds with its recommendation. “Responsivity” implies sensitivity to each offender’s particular characteristics and needs, while the recommendation is that most offenders receive better rates of desistance over time[32][33][46-48]

- Learning to see one’s self as an active “agent” in one’s own life, capable of and responsible for making changes;

- Developing a personal identity that extends beyond crimes committed;

- Shifting one’s associates from antisocial to prosocial people;[28-42] and

- Changing from antisocial to prosocial roles, such as stable employment and satisfying intimate relationships.[43-45]

These changes in self-identity and social support networks and roles frequently translate to changes in behavior and vice versa. Within stable networks such as family or close community, changes in how and what kinds of support arc exchanged also coincide with changes in behavior. “Good company” appears more influential on behavior than will power, especially for offenders who struggle with low self-control.

Understanding that these particular changes correspond to better rates of maturation out of crime, officers may help offenders make these changes by assisting them in making prosocial shifts in their networks and roles. Network shifting capitalizes on the potential for offenders’ social support networks to model and reinforce either prosocial or pro-criminal behavior and attitudes. As offenders participate in new networks including AA, faith-based groups, martial arts, their informal controls are enhanced by the behavioral reinforcement of new significant prosocial others in their lives who inadvertently provide “alternative supervision” by discouraging criminal behavior.

This supervision strategy of Social Network Enhancement (SNE) was a key element John Augustus’ work in the 1800’s to help offenders re-establish ties with their families, move to new neighborhoods and form new prosocial networks. Currently, it is a core element of the National Institute of Corrections (NIC) model for reducing recidivism, affirming the need to assist offenders in engaging on-going support in their natural communities.[83] The skills involved in facilitating network changes include:

- Exploring the possibilities for clients to engage with new prosocial networks (hiking clubs, churches, mosques, tribes, YMCA, etc.);

- Introducing clients to vetted social-supporting others (SSO’s) or coaching existing members of the client’s network to become more supportive of the prosocial changes the client is working on;

- Offering clients a menu of new support options based on an awareness of the formal and informal organizations that support community in their local neighborhoods; and

- Using MI to explore the client’s ambivalence and low sense of self-efficacy around engaging current and other possible social networks in a prosocial way.

Among the variety of prosocial networks that are available to support offenders, 12-Step programs like Alcoholics Anonymous have proven to be particularly effective. Beginning with research findings from Project MATCH,[78] the evidence supporting the efficacy of 12-Step programs has rapidly expanded and increased in quality. In the past ten years, over 30 studies have demonstrated the direct and significant effects of AA on reductions in days of drug/alcohol use. Two of the significant causal elements for AA include: program involvement or participation – working through the steps with a sponsor, service work and 12-Step work – and frequency of contact and interaction with others in the recovery affiliation. Researchers in Europe have recently succeeded in testing interventions that mimic AA’s network-shifting abilities without the 12-Step ideology and found similar efficacy in reducing drug use.[38-40] The combined evidence for 12-Step programs such as AA, NA, CA has elevated this type of treatment to advanced evidence-based treatment status in the addictions treatment field.[28][79-82]

Combining the Desistance literature support for the effectiveness of network shifting in helping offenders mature out of crime with the research on 12-Step networks’ effectiveness in reducing addictive behaviors, we recommend Social Network Enhancement as the fourth strategy of our new model. Twelve-step programs should be a key element of prosocial network shifting whenever this kind of treatment is applicable to client needs.

In summary, these four bodies of research—General Factor, Contingency Management, What Works and Desistence—provide both general guiding principles and resulting specific evidence-based applications for our model. The evidence from these literatures strongly recommends four probation officer skill strategies that will improve officer satisfaction and offender outcomes:

- Using accurate empathy skills to form collaborative working relationships that help clients to build their own internal motivation for change;

- Applying cognitive-behavior treatment interventions to particular client need areas, especially for clients who are at high-risk for future crime;

- Systematically rewarding prosocial behavior and punishing anti-social behavior; and

- Supporting clients in building an internal sense of agency, developing their identity as prosocial community members and expanding their prosocial reinforcement from existing and new prosocial networks.

TRANSLATING THE MODEL INTO PRACTICE

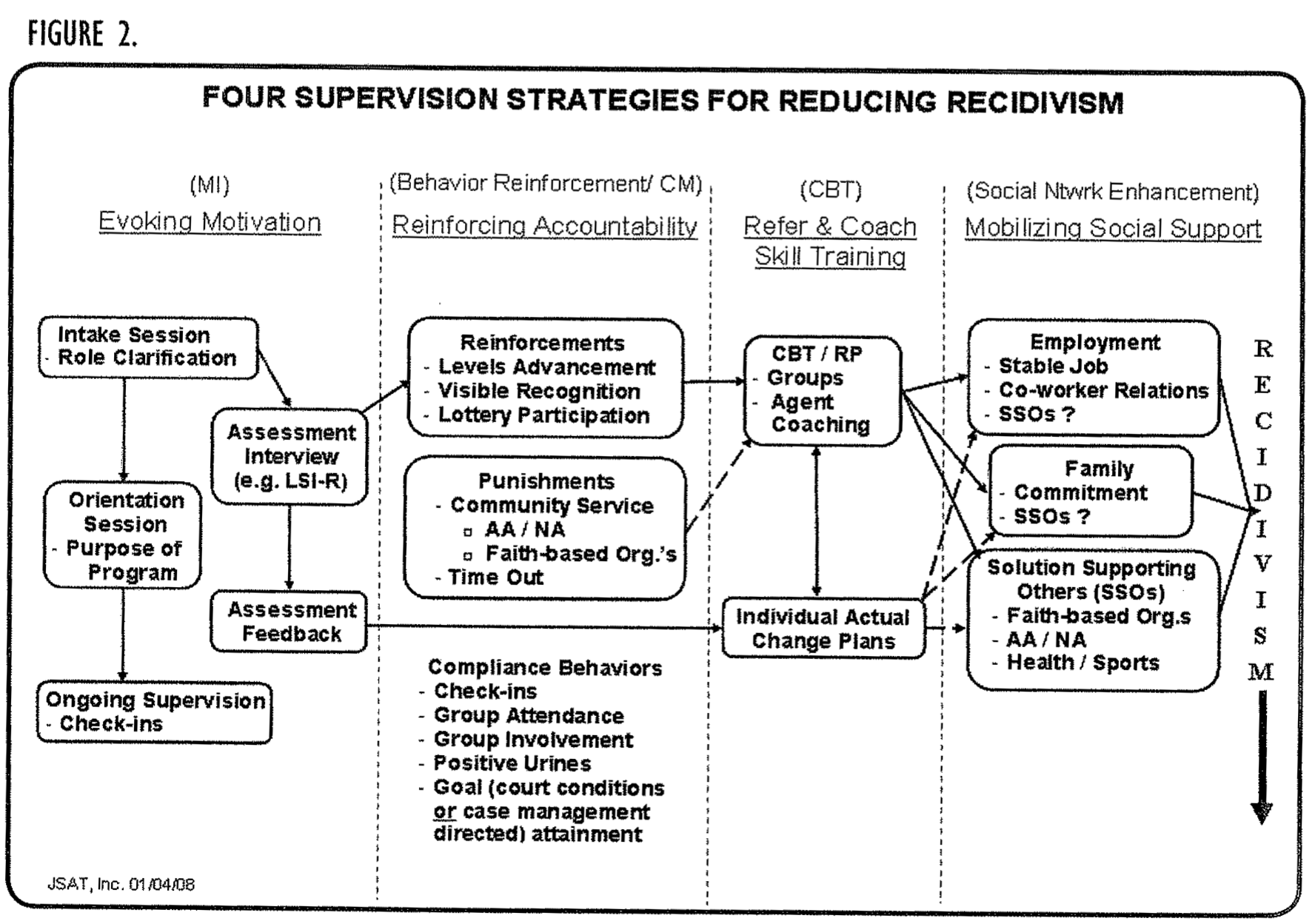

In the following model, we set out the four officer strategies outlined above with attention to the order in which they are most likely to occur and be most effective. The very first thing officers do is create and set the tone for the working relationship they will have with their clients. Then, officers set up the way in which terms and conditions of supervision will be applied. Influencing the cognitive behavioral development of clients requires more time than the first two. Finally, even more time is usually required before officers can help clients, especially those who are moderate and high-risk, to enhance their social networks. If each of these stages in the collaborative journey of client and agent combine and weave together in a synergistic way, outcomes that are satisfying for both the client and the officer are likely to result. Figure 2 lays out the connections between these four skill sets and shows their chronological progression. Following figure 2, we take a closer look at what it means to work with these four sets of officer activities or skills in a combined manner.

ESTABLISHING A WORKING RELATIONSHIP AND EVOKING MOTIVATION

From an MI perspective, establishing an effective working relationship with a client and evoking their inner motivation for change is largely a function of accurate empathy, good listening and the use of skills that help to direct conversations toward exploration of the changes clients want to make in their lives. When a good working relationship has been established, these kinds of conversations can take place whenever clients get stuck or stalled in ambivalence about making changes. MI techniques can help clients to get started in a new direction, discovering their own solutions to overcoming the problems in their lives.[139] Because developing a working relationship is key for the effectiveness of MI, it is essential to begin the process of establishing a working relationship and evoking motivation right from the very beginning of the case management process. This is the time when the kind of relationship and the respective roles between the officer and client will be established, so it is important for officers and agencies to do everything in their power to enhance the likelihood that this process of establishing working relationships and increasing motivation will be successful from the very beginning.

The process for making appointments, the way in which the staff at the front desk greet clients and the very first appointment with an officer all provide opportunities for staff to use active listening skills that will decrease the defensiveness of clients and improve client expectations for success. These initial contacts arc prime opportunities for setting the tone of supervision, clarifying officer and client roles and improving the expectations clients have for supervision. Because of this, many agencies are now using MI approaches for conducting risk, need and responsibility assessments with offenders; for setting the terms and conditions of supervision; and for “feedback sessions” that follow upon assessments such as the Level of Service Inventory or the COMPAS and give the client objective feedback from their assessment results.[147;148] Using MI in this fashion improves officers’ knowledge of their cases and increases clients’ openness and motivation to participate in their own change processes. Deeper knowledge about the client’s criminogenic needs and the motivational factors that they most resonate with, can be extremely helpful to an officer who will have to monitor client compliance with terms and conditions. An MI feedback session following assessment can really help clients to identify and reinforce any personal change goals that they might be harboring. This is the point where a real working alliance begins.

The literature on motivation clearly indicates that intrinsic motivation to change is far more durable and effective than motivation from the outside.[136-138] Among the over 200 randomly controlled trials on MI[69][70][140] are dismantling studies that investigate what its mediating or causal ingredient(s) are. An important causal mechanism for MI is the elicitation of frequent and stronger intensity “change talk” from clients—statements that move from expressions of desire to change or capacity to change to commitment to do so.[71-73][141][142] Consequently, it makes sense to define the output for the motivational component of this model as frequent and/or intense change talk the offender’s particular criminogenic needs as directly as possible at a level that is appropriate to the offender’s risk level.

There are two primary ways to’do this. First, the agent can expedite the treatment process through an assertive referral technique in which the officer shares responsibility with the offender for:

conducting a timely and valid assessment of the client’s risk, need and responsivity factors;

assigning the client to the most appropriate kind and dose of treatment available;

getting the client started in treatment expeditiously;

briefing the treatment practitioner on the exact nature of the client’s risks and criminogenic needs;

using supervision contacts to review and affirm the skill goals and progress of their clients.

In combination with building a working alliance with MI and executing CM with fidelity, these strategies will ensure that the client’s “dose” of CBT is optimized in terms of formal treatment.

Second, to the degree that agents are successful in building a working alliance with clients, they can intermittently provide brief CBT coaching sessions to clients within the context of supervision contacts.[149] Many agents are quite familiar with various cognitive-skill building techniques and can apply these during supervision. In addition, agents can draw on the help of lay persons and paraprofessionals who can apply CBT approaches once they have been trained.[147][150][151] Several skill-building curricula and books have been designed to facilitate this process for agents.[15][152] The research on CBT implementation[153][154][155] indicates that coaching beyond the formal training setting for CBT is essential if CBT is to be considered an EBP. If officers can coach a client for five to ten minutes on some aspect of problem-solving, they can enhance public safety and save themselves from many of the problems and time consuming activities that are associated with the proceedings for client technical violations.

Results from CBT depend on the adequacy of any formal treatment the client is referred to in terms of the actual amount of time clients are in treatment, the amount of assigned CBT homework completed and the number of informal CBT coaching sessions the client received from the agent to complement formal CBT treatment delivery. Increases in any of the above should affect the client’s self-control skills, work-related skills and social efficacy.

SUPPORTING THE EXPANSION OF PROSOCIAL IDENTITY AND SOCIAL SUPPORT

Because of their deep knowledge of local networks and formal and informal organizations, many officers arc well-positioned to support the growth of offenders’ prosocial identity and the expansion of their social support. The skills commonly used for helping others to make shifts in their social roles and networks are similar to those required for promoting networking abilities. Agents can establish contingencies that “bribe” or “nudge” the client into an expanded prosocial networks and social participation (e.g., “If you attend 90 AA meetings in 90 days or play in a local basketball league for the next three months, I will reduce your supervision period by six months.”).

Another strategy is directly introducing clients to vetted social supporting others commonly known as SSO’s who are prepared to mentor or support offenders within the context of the socially rich networks that they belong to (e.g., faith-based organizations, martial arts schools, 12-Step groups, political parties and leisure oriented groups such as bowling or basketball leagues). If officers have good working relationships with their clients, they can match clients’ particular needs and characteristics to the most appropriate kinds of social networks. Officers can use MI skills to help their clients explore the costs and benefits of failing to make appropriate shifts in their social support networks. Because the issue of social support networks is tremendously important in the desistence process, officers should begin investigating each client’s social support network during the assessment phase of their working relationship and then reinforce any positive changes in this area during supervision. When a person’s network or social context changes, their thinking and their behavior changes:[41] context conditions consciousness.

Measures for social support include the size of an individual’s social network, the frequency of contacts they have with prosocial others and the frequency of prosocial modeling and vicarious reinforcement that occurs through mentor-like relationships such as with 12-Step program sponsors. Once again, higher elevations on these measures will contribute directly or indirectly to better outcomes for work performance, self-control and general prosocial support.

SHIFTING THE FOCUS OF SUPERVISION FROM TERMS AND CONDITIONS TO CRIMINOGENIC NEEDS

Research on officers in the field suggests that most agencies and officers put the majority of their time and resources into managing the terms and conditions of their clients and focus only peripherally on addressing the primary criminogenic needs of offenders.[3-5][143-146] For many reasons, this is not surprising. The terms and conditions of supervision have legal standing and so it is natural for agents to give them some priority. The public expects offenders to be held accountable to their terms and conditions and wants correctional agencies to be held accountable.

However, the terms and conditions of supervision are often formulated by judges and parole board members whose experience and formal training have little to do with the psychology of criminal conduct and the process of facilitating desistence from crime. Furthermore, judges and board members frequently lack access to reliable assessment information about the offenders who come before them. When they do have accurate assessment information, judges and board members are often unable to interpret the information and correctly identify the major criminogenic needs of the offender. In some instances, officers do not have access to accurate assessment information either and may also lack training in how to interpret and apply the results of assessment. Many officers have high caseloads and few resources to meet the considerable needs of many of their clients. As a result, officers often feel that they are lucky if they can even manage to focus on just the terms and conditions of supervision. Other officers feel convinced that a strong focus on terms and conditions is the best approach to reducing recidivism.

All of this means that agencies and officers face significant challenges in the effort to add additional areas of focus. Terms and conditions are usually established in the initial phases of the encounter between an officer and their client. As we said above, this means that the first few encounters between an agent and an offender sets a course for most of the subsequent supervision process. Despite the fact that many officers are well-qualified to the play the role of establishing working relationships with their clients, helping them to identify and prioritize the criminogenic needs of their clients, recent research indicates that officers are generally not performing such roles and responsibilities. Perhaps what is missing is a clear agency mandate and roadmap for how to perform this function.

The model we have described posits that community supervision necessarily requires a focus on terms and conditions. However, we argue that this focus on terms and conditions should be subsumed into a systematic approach to identifying and addressing the criminogenic needs of offenders through a collaborative working relationship with their supervisors, other treatment providers and solution supporting others. Agent MI skills help to awaken and deepen the offender’s motivation to actively participate in their own change process. A systematic approach to applying terms and conditions in a way that is faithful to the principles of contingency management helps offenders to stay with their assigned obligations and treatment requirements long enough for their dose” of CBT skills to kick-in and help them make progress with their criminogenic needs. When agents expedite referrals to cognitive-behavioral treatment and provide informal CBT coaching for offenders that helps offenders to build stronger self-regulation, thinking and social skills that enable them to reclaim more prosocial roles and lifestyles within their communities. By supporting the naturally occurring shift that clients are then able to make toward more prosocial communities, officers can help offenders to engage with the most appropriate communities-of-practice within their neighborhoods where they can practice and receive reinforcement for their fledgling new prosocial skills. In many supervision relationships, therefore, the burden and responsibility for much of the change work will be shouldered by the offender in a way that is satisfying to both the offender and the officer.

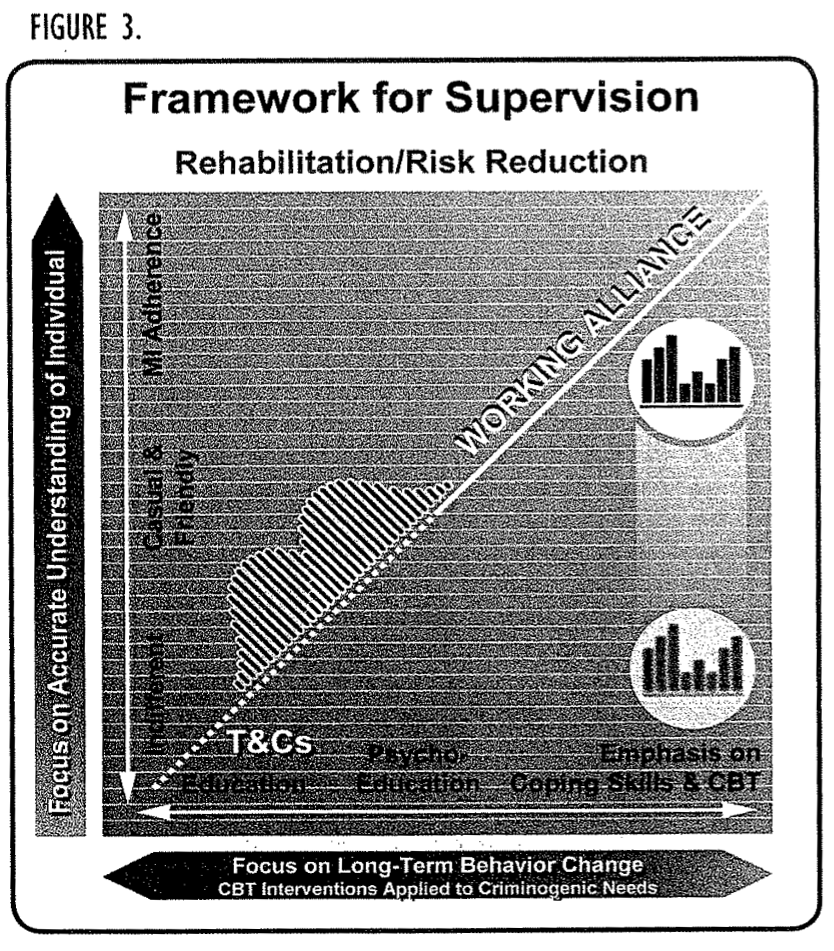

When this occurs, officers will then be able to shift their work from a primary focus on terms and conditions to criminogenic needs to the extent that they have two core competencies: the ability to get better acquainted with clients’ sources of motivation and the underlying criminogenic conditions of their life situations and the skill to apply CBT interventions and direct CBT coaching to clients. Figure 3 shows how development of these competencies interact, resulting in progressively less work for officers. These competencies can provide a natural momentum for the officer-client working relationship that results in reduced recidivism.

The vertical axis of Figure 3 represents the degree to which the practitioner has an accurate, current understanding of the client. The horizontal axis portrays the practitioner’s direct involvement and ability to apply CBT skills that address offenders’ criminogenic needs. The vertical axis, depicting an accurate understanding of the client, ranges from a nominal, limited knowledge of the case, to a direct, personal and broad understanding of the person and their motivations, attitudes and skills as related to criminogenic factors. We have seen above that MI skills generally facilitate such broad and deep understanding. At the upper end of the continuum, the practitioner has the ability to connect meaningfully with individuals through training in both MI and forensic psychology (e.g., knowledge of criminogenic needs).

The horizontal axis represents the ability of the officer to engage the offender in cognitive-behavioral techniques and strategies. On the low end of the horizontal axis, the officer places little or no emphasis on selecting interventions for the client that are faithful to CBT principles and strategies. At the high end, the officer strongly emphasizes and facilitates such interventions. In between the low and high ends of the horizontal axis, the various types of treatment range from simple educational or awareness classes, to psycho-educational groups, to experiential eclectic groups and therapies. to CBT. The goals for CBT-type treatments are assumed to be criminogenic factors (e.g., dysfunctional family relations, anti-social peer relations, alcohol and other drug problems, poor job skills, poor time management, low self-control, anti-social values and anti-social personality features). Officers can only apply CBT correctly when they also have an accurate understanding of their clients’ particular constellation of criminogenic needs.

Together. the horizontal and vertical dimensions meet at a place that establishes a framework for building a strong working alliance between officer and client, allowing them both to move beyond the mere enforcement of terms and conditions to effective change strategies. When either of the two dimensions is ignored, the supervision process is neither efficient nor effective. When officers have little understanding of clients’ motivation and criminogenic needs, but gets clients into a good CBT program, some of their criminogenic issues may be addressed, but others are likely to be ignored. Even when the CBT program does address pertinent offender needs, the offender will suffer from the lack of personal engagement in the referral and the imprecise fit that is common to pre-packaged intervention programs delivered at the group level.

On the other hand, if officers emphasize accurate understanding of clients, but overlook CBT skill development, this will likely foster reactive supervision. Tending to day-to-day client crises will assume unnecessary priority over proactive and strategic goals aimed at the root causes of criminal behavior, rather than the daily “symptoms.” In this scenario, officers will experience the familiar exhausting cycle of endless trouble-shooting that results in short-term behavioral change at best. In contrast, the model we describe has a logical, testable relationship to reductions in recidivism and is proactive in nature. For this reason, the model is likely to result in a much more emotionally satisfying process for both the officer and the client.

FOUR STRATEGIC COMPONENTS OF A LOGIC MODEL FOR COMMUNITY SUPERVISION

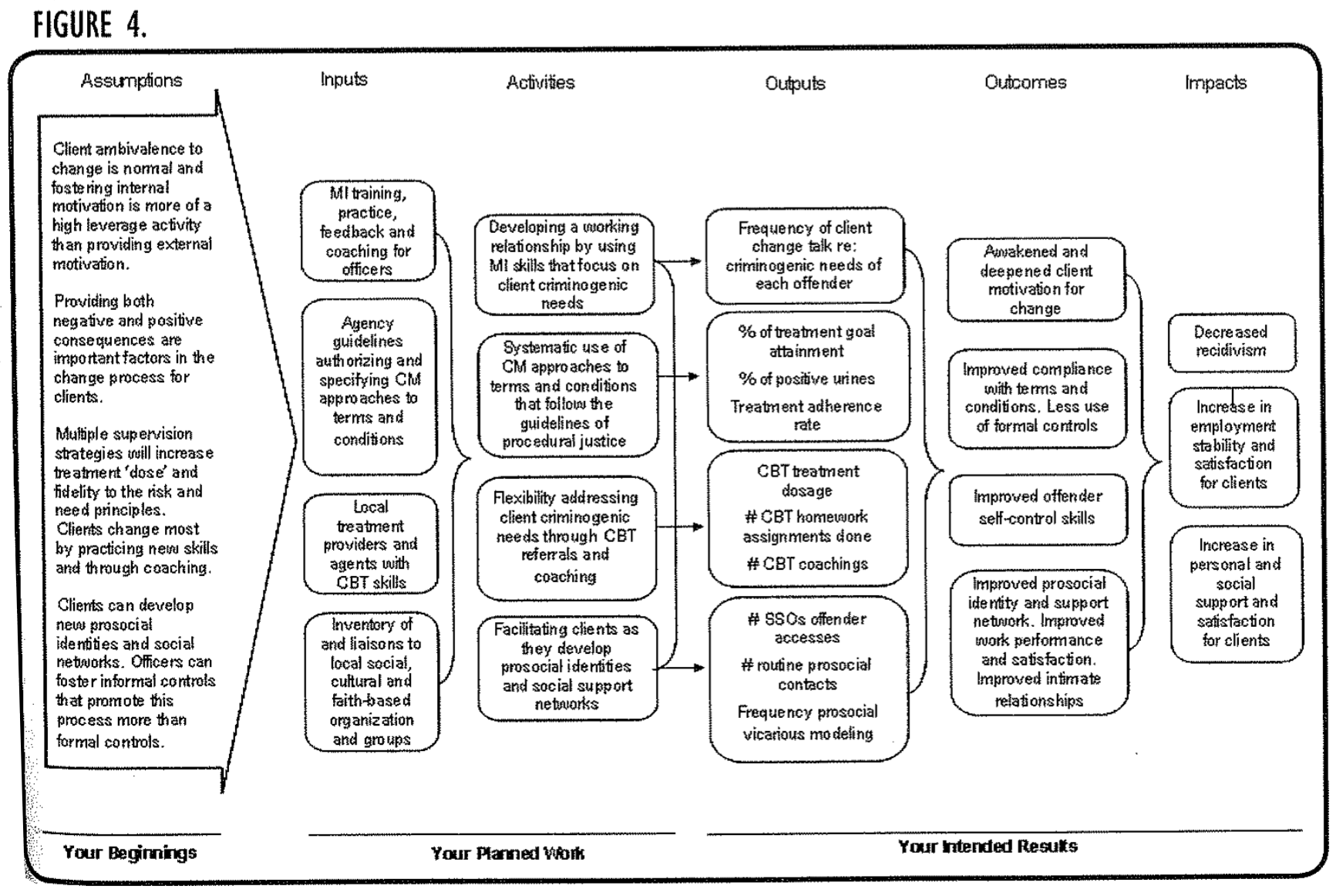

The scope of this article does not permit us to fully explore the causal or logical relationships between the various components of the model we have described. But a brief description of the logic of the underlying relationships behind our model may prove helpful. A “logic model” graphically depicts the core components of a human service or business program and shows the causal relationships between the components of the model and the anticipated outcomes from implementing the model .124 Tie model should convey the underlying reasoning behind why and how a given program is likely to produce a particular effect or impact. Logic models help government agencies to clarify the specific objectives of a program and establish how the program fits into the overall mission of the agency.[125]

Currently, there are no published examples of logic models for community supervision in the field of community corrections. If we assume that the right combination of the four officer strategies or skill sets and their evidence based principles discussed above will contribute to sustained reductions in recidivism, we can begin to build a generic logic model for how community supervision is apt to improve public safety. Figure 4 organizes the main components of our model into a chronological or temporal order, conventionally either moving left to right or top to bottom. In this fashion, the model builds on an “if.. then” set of assumptions about how the model works.[124] A close reading of the four sets of general assumptions, agency inputs, officer/offender activities, outputs, outcomes and impacts should reveal the relationships and logical flow across these differentiated components of the model. Future papers will unpack these relationships in a more extended fashion.

CONCLUDING COMMENTS AND POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF THE NEW MODEL

The major policy implications for this model include a shift to an “ecological perspective” to promote a more efficient use of supervision resources and development of staff and agencies in ways that cohere with the model and with EBP in general.

ECOLOGICAL EFFICIENCIES

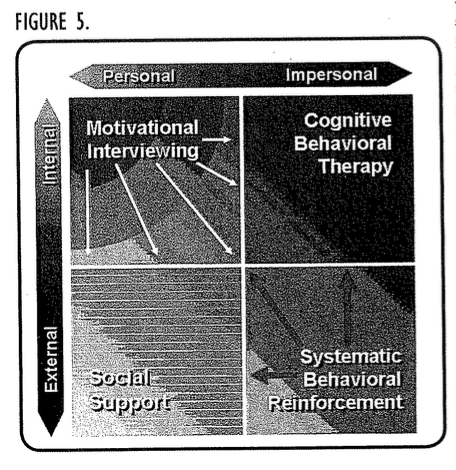

This model can help policy makers in community corrections to develop an “ecological perspective” that can enhance the general framework for community supervision. The model gives rise to an opportunity for agencies to clarify what the highest leverage activities might be for supervision and then to adjust their policies accordingly so that agents are no longer caught up in unrewarding and low leverage tasks. All of the four strategic activities in this model are mutually reinforcing. Progress in any one area has an impact on the other three areas. For example, if a clients’ social support declines, that will decrease their opportunities to practice and be reinforced for their new cognitive-behavioral (CB) skills. Conversely, if clients’ CB skills improve, they will be more likely to comply with their terms and conditions and navigate new social support networks. Each of the four strategies also make a unique contribution to desirable outcomes, either directly or through their effects on other strategies. MI can unleash motivation in a positive new direction for a client and thereby decrease their need for external reinforcements (CM). Significant improvements in social support may alleviate the need for CBT interventions because of the ability of the new social support to model CB skills.

The principle emerging here relates to parsimony: the combination of supervision strategies that produce the most cost effective long-term change. Provisionally, it appears that the more officers can engage their clients in an internal, personal level the more their clients will have energy for change. On the other hand, the more officers engage their clients with impersonal and external methods of control, the greater will be the demand for agency resources. If this analysis is correct, there should be a premium placed on the quality of officer-client working relationships. Presently, the capacity for relationship-building toward a common work goal does not factor large in how agencies recruit, train, and reinforce their agents.[25][149]

STAFF AND AGENCY DEVELOPMENT

The foundational skills within this logic model present agencies with challenges in two areas including: developing the skills among the staff and developing the people who are learning the skills. The majority of the skills that officers need to supervise clients in accordance with this logic model are teachable skills, but some are harder to learn than others. For example, learning to assess offenders’ risk levels and criminogenic needs or learning to use software that can find the CBT programs in an offender’s area are easier skills to learn than those required for engaging in relationships characterized by MI Spirit. Learning MI often requires a fundamental shift in officer beliefs about how people change and in how officers approach interpersonal interactions. More difficult skills require more extensive training with particular attention to post-training practice strategies. Meta-analyses on training indicate that translating skills into practice requires not only a one or two-day workshop, but also follow-up feedback and coaching, using performance measures that can reinforce officer competency development. Such officer development also requires an organizational climate within the agency that supports the shifts in practice recommended by the training.[153][156]

Learning these kinds of MI skills also requires officers to be willing to grow emotionally and socially and to doggedly practice the new skills until they achieve competency in them. Individual cognitive and emotional limitations may combine with unsupportive organizational climates to produce burnout and frustration. While some individual and organizational limitations may be overcome through changes in policies, case load size, added performance measures that reinforce skill acquisition and individual coaching for those who most strongly resist learning, some changes will still not occur as a result of these measures. Therefore, intentional recruiting and hiring of staff with new capacities and attitudes toward supervision may be the best way to bring about gradual changes in organizational climate and to increase the overall skill level of officers.

The skills required for MI—accurate empathy, ability to support client autonomy, collaboration and evocation of internal motivation to change—arc typically the hardest for people to learn if they have a habit of approaching people from authoritarian, rigid or punitive stances. Screening new hires to ensure that they already have the belief that most offenders want to and can change, as well as the interpersonal capacities required for effective MI work, will go a long way toward shifting organizational climates and facilitating the acquisition of EBP skills. By doing so, agencies will bring their supervision models and daily supervision process more in line with a combination of EBP approaches that truly help offenders to desist from crime and thus increase public safety.

ENDNOTES

- Augustus, J. (1984).4 Report of robe latbon ofJohn Ansurtnr. Boston. MA: American Probe• don and Parole Association.

- Paersilia. J. (1998). Probation in the United States – part 1. Antillean Probation and Parole Arsodation(Spring 1998). 30-41.

- Sonia, J. Roger, T., Sedo, B.. & Coles. R. (2004). Cox Mane:mum- in Manitoba Probation 2004.01.Rctrieved. from.

- Sonia.), Rogge, T., Scat. T., Howson, C.. & Yessinc. A. (2007). Eaploring rhe Nark Box of Conn:unity Supervillon: Manitoba Department of Justice (Cocrections).

- Boger. B, Vanderbilt, R.. & Ehret. B. (2007). Contratiart CSSD Recidivism Report 11fee. Samples Year 1 and Year 2 (Juvenile °Arden). Wethersfield. CT: Connecticut Judicial Branch. Come Support Services Division.

- Bonta.)..& Andrews. D. A. (2007). Risk•Need•Rasponriviry Model for °Ander Autrunorr and Rehabilitation: Public Safety Canada, Carleton University.

- Andrews, D. A., Zinger. L. Hoge, R. D.. Bona. J.. Gendreau. P.. & Cullen, F. t (1990). Does Correctional Treatment Work?: A Clinically Relevant and Psychologically Informed Meta•Analy. sit. Criminology, 28(3).369.387.

- Lambert, & Barley. D. E. (2002). Research Summary on the Therapeutic Relationship and Psychotherapy Outcome. In). Norcross (Ed.). Prythorbenspy Refariotublin Dar Wont: Thancpirr Connibtaion r and Revonsittenem ro Patient, (pp. 17-28). London: Oxford University Press

- Bottler, L., Malik, M., Alimohamed, S. Harwood, T., Taktri, H., Noble. S.. et J. (Eds.). (2004). Tbentpist Variables (5th ed. ed.). New ‘ado Wiley.

- Carroll, K. M., Nich. C., & Rounsavale, B.J. (1997). Contribution of the Iherapeaude Alliance to Outcorne in Active Versus Control PsychotherapiesJournottetonsufring & Clinical 1,,,ehologl, 65(3). 510-314.

- Engle, D. E, & /Vicomte, H. (2006). Ambiusleneeia Povitothempy (I ed.). New York. London: The Guilford Press.

- Norcross.). C.. Bender. L. E.. & Levant, R. F. (2006). Hoirlexcalased Nude., in Mental Heald, (First ed.). Washington: American Psychological Association.

- Castonguay. L. G.. & Constantino, M.J. (2006). The Working Alliance: Where are we and Where should we go? Potholing,: Amy. Ramo& Post. Traininc, 43(3). 271.279.

- Palmer. T. (1991). The effectiveness of intervention. recent trends and current issues. CM. Delicaptotry. 37(3). 330-346. 01T

- Palmer. T. (1992). The is.orropme icersivnend rues-nun.. Newbury Park. CA: Sage Publications, In

- Palmer. T. (1984). Treatment and the rob of classification. Crime & Dampineo, 30. 245.267.

- Palmer. T. (1995). Programmatic and non provammoic aspects to successful intervention, New directions for research. Ober 0. Drisafreary. 419).100.131-

- Palma. T. (1995). Posoesorato e eat 14e.Pograrronetie Asp., efSarrenfat hatimention, New Dins.. fire Roeerch.

- Palma, T.. & Nero:wino. A. (2003). The ‘Erfehmentss8 Agency .. 2713). 228.266.

- Palmer. T. B. (1973). Marching weaker and dime in corrections. &vie! Wok. 18(2). 95.103.

- Andrews. D. A. (2006). Enhancing Risk-Nced Rtsponsiaty: Making Cality a Matter of Policy. Croninslogyara Pub& Nag. S(3). 595-602.

- Dowden. C. & Andrews. D. (2003). Dom Family Intervention Work fa Delinquents? Results of a bleta•Analysii Cotedian loose! etriasiscalorr(45,3).

- Loose. E. Cullen. F.. & Cadman. P. (2002). Ekyond correctional quacery, Professional. ism and the possibility of effective eroannit fralord Prgartran.

- Horvath. A. O.. & Symonds. B. D.(1991). Rank* Benton Working Alliance and Out-come in Psychotherapy: A Meta•Analysialtoossal efCaosadttng ck anted PrIdaalers 38.139149.

- Deaden. C. & Andrews. D. (2004). The Importance of Staff Practice °divans Effective Correctional Trcarnwnt: A Maa•Analyee Review of Coo Coreccoosul Practice. Isomationel lomat! ijOfforder Therapy eS Conspentthe Crinniebre. 44(2).203-214.

- Ekon. D. (2001). Yinstk Voloort Repeat ItIcc Storm Booklet: Center for the Study and Prevention of Viola=

- Tonigan. J. S. & Miller. W. R. (2005). A 10.Year Seedy ed-AA Attendance ofTreortme. Seeking Individuals: How Effective k Twelve Seep Fonlication? Unpublished Poster. Center on Alcoholism. Substance Abuse. and Addictions (CASAA). Uairestary of Now Meseta

- Mom. R. H.. & Moos. B. 5. (2004). Long Tenn Infkmace of Doneion and Frequency of Participation in Akoholics Anonymous on Individuals With Alcohol Uat Disorders. Jorounf tf Considringend CGaird Proholov. 72(1). S1-90.

- Vaillanc, G. E. (2000). Adaptive Mooed Meckunimo, The* Role in a Positive Prathaogy. American Pothebesr, 550), 89.98.

- Vaillant, G. E. (1983). 77se Aincra /Amory “‘Alas.’s’s.. Iterereed Cambridge. Musschu. rens, Harvard University Press.

- Martina. S. & Inunarigeon. R. (2004). 46rt CmrardPaostdmeo Pedni.1 to Of Reintersties Portland. Oregon: Willan Publishing.

- Moron. S. (2001). Making Good: If. Ex-Caw. tr Re*. Ala R4-.d.d Mere Lam. Wash. ington. DC, American Pswhological Association.

- Martina. S. (1997. March 1999). Daises. e on I Derciapooto The Prishasoiref Prow of reins Smite:: Paper mama at the The British Crininoksy Co.acreson Belfast

- Denain, N. K. (1987). The Areasemng (Tdal. 2). Newbury Park. Bondy Hill. London. New Date Sage Publications.

- FamIL S. (2002). RM./row char reefs sire *dery Podrerioi, cord moat end doe-ranokon row. Campton: Willan.

- Farrell. S. (2004). Saial capital and agender teintegratiOn. nu.b.ng probation clesinance focused. In S. Mamma & IL Immarigeon (Eds.). Afire Ma. end psi-dames,: Redwys to gander ornoretort. Portland. OR: Wigan Publehing,

- Hughes, M. (1998). Turning pointy in the lives of you.% inner-city own forgoing destructive criminal behaviours: a Taira..< study. Serial KA Rtlearch, 22(3). 143-151.

- Copello. A.. Williamson, E. Orford,)- & Day. E (2006). bnpkmenting and evaluating Social fkiaccions and Network Therapy in dog trekriume presence in the UK: A freatarelrry nay. dridiaire Behavior. 31(5), 802.810.

- LM. M. D. (2003). The Design of Social Support Networks for Offenders in Outpatient Deng Memnon Foferal Probation, 67(2). 15-21.

- UKATT. (2005). Effecciveness of ttruseent for akohol probkom findinp of the randomised UK alcohol treatownt trial (U KATT). BHP drtruk Melecalf.”–4 331(7516). 541-544.

- Moos. R. H. (2003). Social Comes. Transcending Their Power and The Fragility. eimor-onsfoo. 1 acCentssimity15)sholev, 31(112).1.

- Moos. R. H. (2003). Addictive Distracts in Comm. Principkt and Poke of Effective Treatment and Recovr.ry. Awirelogyclildlictist fkbareesa /793, 3-12-

- Sampson.R..& Laub.). (1990). Crime and Deviance Over The Lde Course, Tr. Salience of Adult Social Bonds. Arnesicox Sociological Rojas, 55,609.627.

- Sampson. R.). a. L. J.H. (1993). Crime in the making- Pathways and Taman Points Through Life Carnbruisci Remus/ Clairsoriey Pral. 1-305.

- Sampson, R. J. & Laub). H. (2003). Life-Course Daiseers? of snow among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Crissiceiagy, 41(3).555.592-

- Maxima. 5. & Iunatigeon. R. (Eels.). (2004). After Crnse.s.d PeO reoys o 0.f,,,de’Rup.h.. (sr. .1). ora6. Publishing,

- Were M. (1998). Lifocoune transidons and desistance from crime. Criecieclogy, 36(2). 183.215.

- Uggen. C. (2000). Work as a turning point in the life course of criminals: a duration model of age, employment and recidivism. American Sociologital Review, 67.529.546.

- Azrin. N. H.. & Hole, W. C. (1966). Punishment. In W.K.Honig (Ed.), Operant behavor, Areal tfrtstard, and applteation (pp. 380.447). New York: Appleton•Cencury.Crofts.

- Bandana. A., Ross. D.. & Ross. S. A. (1963). A comparative test oldie status envy, social power, and secondary reinforcement theories of identificatory learningg. Journal ofabnormal and Social Psychology, 67(6), 527.534.

- Bandon. A. (1989). Human Agency in Social Cognitive Theory. American Plehologitt, 44, 1175.1184.

- Meithenbaum, D. A. (1977). CognitivaBehavior modification: An integnrtio e approach. New York: Plenum.

- Bigelow. G. E., & Silverman. K. (1999). Theoretical and empirical foundations of eontin• pricy management creatinenti (or drug abuse. In S. T. Higgins & K. Silverman (Us), Montuting behavior change arnangillkit.drug Abram &march On contingent), management intervention, (pp. 1541). Washington. D.C.: American Psychological Association.

- Elliott. D. S.. Apron, S. S., & Canter. R.J. (1979). An integrated theoretical perspective on delinquent behavior. fournebiRdrerrh in Crime and Delinquenty(january). 3.27.

- Elliott, D. S.. Hu lainga. D.. & Apron. S. S. (1985). Evplaining Delinquenry and Drug the. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Higgins. S. T.. Silverman. K.. & Heil. S. H. (2008). Contingenty Management in Subtrance Above Treatment New York: The Guilford Press.

- Morgenstern. J.. & Longabaugh. R. (2000). Cogn irive-behaviora I treatment for alcohol dependence: a review of evidence for its hypothesized mechanisms of action. Addiettort. 95(10), 1475.1490.

- Bogue, B.. Campbell, N.. Carey. M., Clawson. E.. Faust. D.. Florio. K., es al. (2004). Implementing Evidence-Based Practice in Community Corrections: The Principles of Effective Intervention (Electronic Version), 21. Retrieved April 30. 2004 from lurp://www.nicicmg/ pubs/2004/019342.pdf.

- Lipsey, M. W. (1992). The Effects of Trearmene on Juvenile Delinquents: Results from Meta•Analysis.

- McGuire, J. (2002). Evidence-Bored Programming Today. Boston. MA: International Cons. munity Corrections Association.

- Am. S., Miller, M.. & Drake, E. (2006). Evidence-Rated ask corrections propums: What workt and what dots not Washington Stare Institute for Nike Policy.

- Gottfredson, M. R., & Hirschi. T. (1990).4 Gemmel Theory efCrime. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Miller, W.A., Westerberg. V. S.. & Harris. R.J. (1996). What predicts relapse? Prospective taring of antecedent models. Addiction, 91(12).51554172.

- Hutchins, H.. & Burke, L. (2006). Has Relapse Prevention Received a Fair Shake! A Review and Implications for Future Transfer Research. Haman Remurre Development Bevies’, 5(1).8-24.

- Irvin.). E.. & Bowers. C. A. (1999). Efficacy of relapse prevention: A meta•analytie review. Journal fConarltingand Priebology, 67(4),563-570.

- Carroll, K. M. (1996). Relapse prevention as a psychosocial treatment: a review of mn. trolled clinical trials. Experimental /and Clinical keliopbarmtecology, 4(0,46-54.

- Burke. B. L., Adtowies, H. & Menchola, M. (2003). The Efficacy of Motivational Inter,riew• ing: A Meta.Analysis of Controlled Clinical Trial. Journal a/Counseling end Clinical Pryobology, 71(5).843.861.

- Hettema. J.. Sleek ). & Miller, W. R. (2005). Motivational Interviewing. Auroral Review ay. Clinital Poebology, 1(1).91.111.

- Rubak, S., Sandboek. A.. Laurier-en. T.. & Christensen, B. (2005). Motivational interview. ing: A systematic review and meta.analysis.BritishfourrtlefGrnerelPrarrien 55(513). 305.312.

- Vasilaki, E. I.. Hosier, 5.G.. & Cox, W. M. (2006). Tice Efficacy of Motivational Interview-ing as a BciefIntervention For Excessive Drinking: A Mera.Analytic Review. Alcohol Aleoholion, 4/(3).328.335.

- Amrhein, Miller. W. ft„.. Yahne. C. E.., Palmer, M, & Far. !cher. L (2003). Client Com-mitment Language During Motivational Interviewing Predicts Drug Use Outcomes./carnal of Come/ring and Clinkal Psychology, 71(5). 862-378.

- Carley. D.. Harris. K.J. Mayo. M. S.. Hall. S.. Okuyerni. K. S. Boardman. T.. a al. (2006). Adherence to Principles of Motivational Interviewing and Client Within•Sitition Behavior. Ikkao-ioured er Cognitive Prydrotherapy, 43.56.

- Moyers.T. B., Martin, T. Manuel). K. Hendrickson. S.. & Miller, W. R. (2005). Awning competence in the use of motivational intetvicwing.loarnal a/9;46,461w Aux Treatment, 28(1). 19.26.

- Miller. W. A., & Mount. K. A. (2001). A small study of training in motivational interview-ing: Does one workshop change clinician and them behavior ?Behaviosoul & Cognitive Prycho• therapy, 29(4).457.471.

- Corbett. G. (2006). What the Research says…About 341 Training. MINT Bulletin, 13(1), 12.14.

- Miller, W. R., Yahne. C E, Moyets.T. B.. Martinez. J.. & Pirritanno. M. (2004). A Ran-domized Trial of Methods to Help Clinicians Learn Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Comdr. ing and Clinical P9ehology, 72(6). 10501062.

- Yalme. C. E.. Millet. W. R.. Mores. T. B. & Puritanno. M. (2004). Teaching Motivational Intemiewing to Clinicians: A Randomized Tnal of Training Methods. Center on ideoholism. Substance Abuse and Addictiotu (CASAA).

- Tonigut. J. S. (2001). Benefits of Alcoholics Anonymous Attendance: Replication of Find. ins Between Clinkal Research Sites in Project MATCH. Artaboluak Toronentr&narterl,, 19(1). 67.77.

- Tonlpn.). S.. Owen. P. L. Shyrnakee. McCracy. B. S. Epee,. E E.. Kaskutas. L. A. a al. (2003). Participation in Akoholics Anorrpnows. Intended and Unintended Change Meeks. nitrite Alcoholism: anion! wed Eapeoustons .1 Round 27(3).524.

- McCrady. B. S.. Epuein. E. E. & Kahirt. C. W. (2004). Akoholies Anonymous and Maple Prevention as Maintenance Strategies Afier Conjoint Brtuvioral Akohol Treatment for Men :18. Month Outcomes.Jewnsel tf Consulring nerl Clamed Pneholegy, 72(5). 870878.

- Moos. R. H.. & Moos. B. S. (2004). The interplay between help-seeking and alcohol-related outcomes: divergent menses fix professional treatment and .elf-help groups. Ong & Aleolool Deponienot, 75(2). 155-164.

- Morgenstern.), Laboirrie. E.. McCrady. B. S. KaMa. C. W. & Frey. R. M. (1997). Affiliation With Akoholia Anonymous Aker Treatment A Study of to Tlwrapeutic Effects and Mechanisms of Action. /annul el Censiski ng end CfockefPneirargy 65 (5).768-777.

- Bogue. B.. Campbell. N.. Clawson. E. Faint. D. Sono. K- joplirt, 1- a d. (2004). Implementing Evidence-band Practice in Communtry Corrosion: catkoracion for Systemic Change in the Criminal Justice System (Electronic Vertson). 9. Retrimed June 14. 2007 from hap://w++.

nkkorg/pubs/2003/019343.pdf - Higgins. S. T.. & Silverman. K. (Ed.) (1999). AbrttunngStf.a4, Ohne:, 4.m6 Of”‘ Aug Chem Raeorch on Contingent, Aloongenront bnersnnosoar (Ftry <4.). WashIngton DC: American Psychological Association.

- Meyers. P- ).. & Smith.). E (1995). artsice/ Gant in Aland Tonannosat: an Cowman”, Annfononon: Approach. New York Goilfeed Press.

- Meyers. ft_ J. & Smith.). E. (1997). Getting off the fence: Proadures m engage treatment. resift211( &tokens. Josonsof eSa&onnet Ann’ Toronr,nt, 14(5).447,472

- Aker, R. L (1985). anion Mum, A *int awning smoroac4 (NA ed.). Belmont. CA: Wadsworth.

- Bandon. A. (1996). Medunisms of Moral Disenagemene in the Earteise of Moral Agency. J 7/(2). 364-374.

- Andrews. D. Bona.). 6c Hoge, R. (2003). Classification Ear Effective Rehabiliation: Rediscovering Psychology. ConnOtel Justice end &how; 17(1). 19-53.

- Gcnd tea°. P. & Coggin. C. (2000). the Effects of Coinuatuniry Sanctions and Incarceration on Recidivism. Drpernienst iPsychrilcry. Calesrot 1.&,ronigy.

- Gentkeau. P.. Paparomi. M.. Little. & Goddard. M. (1993). Dom -Pnnishmg Smart.’Work? An Assessment of the New Crtherataon of Akernatrte Sanctions in Probation. Foram On Conornon, &awn& 5.31-34.

- Gendreau. P. & Coggin. C. (1995) Primapito tylifeetiso Corms:ono! Progrownsing sorb Ofenden. University of New Brunswick. New Brunswick.

- Andrews. D. A. (1994). A Saul Lennain g rod Cognitive Appondo to Orme and Cm-arrow: Corr Element, of.Ernionte4Insed Corroononal horeroension (Training Protocol). Ottawa: Carleton Univertary • Department of Psychology.

- Dutton. D. C. (1995). Tee domestic Angola grows: Itn6olorerl And vonssoljostior porn:notion (2nd ed.). Boston: Allyn & Baca,

- Hanson. R. K.. Gordon, A.. Harris. A. J. R.. Marques.). K_ Murphy. W.. (insey, V. L. et a1.(2002). Fine report oldie Collaborarive Ouccanc Dart Project on the effertive-iess of pathological treatment for sex offenders. Solana Alms e. .4 Jamul e “Resocro6 And Trenonsent, 14(2). 167-192.

- Mein. N. H.. Sisson. R. W. Meyers. R_ & Godley. M. (1982). Alcoholism Treatment By Disulfiram and Common icy Reinforce:twee Theirapylotentef cfSrbo.ord 714nql ono’ Pqdrintry. 13(2). 105.112.

- Busks.). (1995). Teaching sdfsisk managernat to ride= ortemkes_ LI J. McGuire (Ed.). WIont 14441: Efichar Inabwir lo r don reaffenting (pp. 139-154). Susses. England: Wiky.

- Sabers. K. W. & Milkman. H. B. (1998). Grinned Condoc• Sobannet Anse Tom, onent.lhousand Oak,: Sage Publications. la<

- Ross. R. R.. & Fabian. E. A. (1985). Tose to Thank: A rognanx model eVe4nquenry prom, tom and ernder rclatitihrerten.Joh.tion City. TN: Inuituce of Social Sciences and Arts

- Preston. K. L. Umbricht. A.. 8c Epstein. D. H. (2002). Abstinence 112116RCITC In trainee. name contingerey and one-yet fellow-up. Dm: d•AlndwIDtpasdence. 67(2).125-137.

- Griffith.). D.. Rowan.Stal. G A_ Roark. R. R. & Simpson. D. D. (2000). Contingency management in outputent methadone create:km: A eneu-analysis. Drug ch .4keitol Dependence. 58(1.2). 55.66.

- Griffith. H. W. (2000). CompInn God r u Pr preenold Novrenripnon Dons (Fat cd.). New York: A Pertga Book.

- bodes. J. P, Heil. S. H.. Manton.). A.. Sedges. G. J, & Higgieu. S. T. (2006). A mere. analysis of yak:her-baud reinforcement therapy foe substance tat disorders. Addicnon. 101(Z). 192.203.

- Petry. N.M. Peirce.). M.. Science. M. L. Blaine. J.. Roil) M.. Cohen a- et al. (2005). Effect of prise.baud incentives on outcomes in stimulant abusers in outpatient psyehol•social treatment programs: A national drug abuse treatment Clinical Trials Network study. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(10), 1148.1156.

- Rawson. R. A.. McCann, M.. Flanunino. E. Shopeaw, S.. Miorto. K.. Reit)… C.. et al. (2006). A comparison of contingency management and cognitive-behavioral approaches for stimulant-dependent individuals. Addiction, 101(2). 267.274.

- Silverman, K.. Wong, C. J., Umbricht.Schneiter, A.. Montoya. I. D.. Schuster. C. R.. & Preston. K. L. (1998). Broad beneficial eifecgs of cocaine abstinence reinforcement among methadone patients. low., of*Comulting & Clinical Psychology, 66(5). 811.824.

- Sigrnon. S. C.. & Higgins. S. T. (2006). Voche r•based contingent reinforcement of marijuana abstinence among individuals with serious mental illness. Journal of SubstanceAbwr Moment, 30(4). 291.295.

- Calsyn. D. A., & Saxon, A. J. (1999). An innovative approach to reducing cannabis use in a subset of methadone clients. Drag & AfrobolDependencr, 53. 167.169.

- Budney. A. J.. Moore, B. A.. Higgins. S. T.. & Rocha. H. L. (2006). Clinical trial of abstincencobased vouchers and cognitive-behavioral therapy for cannabis dependence pinwale/ Coludting d Ginicul Psychology, 74,307-316.

- Budney, A. J., Higgins. S. T., Radonovich, K. J.. & Novy. P. L. (2000). Adding voucher. bared incentives to coping skills and motivational enhancement improves outcomes during treatment for marijuana dependence.fountel efConnthing dr Chnical Povhology, 68. 1051.1061.

- Petry. N. M., Martin. B.. Cooney.). L. & Kander. Ff. R. (2000). Give them prizes. and they will come: Contingency management for treatment of akohol dependence/crime/ a/Cenral. log& Chninel Ptychology, 68, 250.257.

- Miller. P M. (1975). A behavioral intervention program for chronic public drunkenness offenders. Archives eGlentnel Prythistry, 32.915.918.

- Liebson, I. A.. Tommasello, A.. & Bigelow, G.E. (1978). A behavioral treatment of alcoholic methadone patients. Annuls of hamlet Medicine, 89.342.344.

- Carroll. K. M.. & Oaken. L. S. (2005). Behavioral Therapies for drug abuse. American Journal ePurbiorry, 162. 1452.1460.

- Sinha. R.. Easton. C.. Renee-Aubin• L., & Carroll. K. M. (2003). Engaging young probation-referred madjuana•abusing individuals in treatment: A pilot trial. American foarnat on Addictions, 12, 314323.

- Peniscon. E. G. (1988). Evaluation of longterm thenpeutk efficacy of behavior modifica• don program with chronic male psychiatric inpatients.Jourruloprhevier 7heropy one 1 Erpevimental Prydnony, 19.95.101.

- Aztin, N. H.. F/ores. T.. & Kaplan, S. J. (1975). Job.finding dub: A group-assisted program for obtaining employment. Behavior Research and Therapy, 13, 17.27.

- Aadn, N. H.. & Beale’, V. A. (1980). Job club countelori monad Austin. TX: Pro.Ed.

- Milby, J. B.. Schumacher.). E., Wallace. D. Freedman. M.).

- Prendergast. M. L. Hall. E. A.. & Roll.). M. (2005). Judicial mPervidonand contingency management In treating thug.abusingoffindcrs: Preliminary outcomes. Poster presentation at the 67th annual scientific meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence.

- Messina. N.. Farabee.D- & Rawson. R. (2003). Treatment responsivity of cocaine. dependent patients with anitsocial petsonalitydisonier to cognitive-behavioral and contingency management intmentions. formal of Comulting & Clinical P9rholor I, 71. 320.329.

- Harrell. A.. Cavanagh. S.. & Roman, J. (1990. Final report: Finding,front the Enelmation of the District g(Colanold.S.ptrior Court Drug Intervention Program. Washington D.C.: Urban Institute.

- Hs…ken A.. & Kleiman. M. A. (2007). H.O.P.E. for Reform: What a novel prob.. don program in Hawaii might teach other states. 2007. from hup://ww•.peospectorgies/artklesIattkkuhope_for_reform

- Foundation. W. K. K. (2004). Logic Made/ Development Guide: thing Logic Models to Bring Torthe Plonning, Boo/nation, and/knon.Unpublished manuscript. Battle Creek.

- Petersilia. J. (2007). Personal Communication.

- Tittle. C. R., Ward. D. A.. & Grasmick. H. G. (2003). Self Control and Crime/Deviance: Cognitive vs. Behavioral Measutes.fountelof,tuunrinenve Criminology, 19(4). 333-365.

- Sampson. R. J., & Laub.). H. (2005).A Life•Course View of the Development of Crime. The Amok of the American Academy 4.Politieol &SaeidSnrrct 602(November). 12-45.

- Andrews. D. A. (1980). Some Experimental Investigations of the Principles of Differential Association Through Deliberate Manipulations of the Structure of Set vice Systems. 411k77(4A Sociological Review, 45.448462.

- Elliott. D. S. (1994). Serious Violent Offenders: Onset Developmental Course. and Tarnination • The American Society of Criminology 1993 Presidential Address. Crimindav, 32(1).

- Elliott. D. S.. Mound. S.. Rankin. B.. Elliott. A.. Wilson. W.J.. & Huizinga. D. (2006). Good Kids from Bad Neighborhoods: Sucteofid Deodopment in Social Corttext. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Moffitt. T. E. (1993). Adokscenu.limieed and life•course.persistem anuari.l behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychology Revino. /00.674-701.

- Tatman. F. S. (2004). Nan cud Beta e PCS, Prawn.. Consmunty Supenmen. Retrieved. from.

- MacKenx.y. D. L (2006). What :Oakum Carman r: Redwing eln Crmi,.dAmxtia qr ‘hind and Dr/immenn. Cambridge: Cambridge Universiry Press.

- Petemilia, J. (2003). Wlsen bunters Come Hem, Parole esel P,i1HOT Rerun] (First ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cullen. F. & Genclimu. P. (2000). Assessing correctional rehabilitation: Policy. practice and proipems. In J Haney (Ed.). Criminal Amite DM: Voinme 3. Polk.. Preemie. and Decision, esfrhe &ionised isomer System . Washington. DC: Department °flair:cc. National [mum. of Justice.

- Ryan. R. M.. & Dui, E. L (2000). Self.ekterminanon theory and the facilitation of intrin. sic motivation. social development. and well-being. American Psyeinsfelgut. 55(1). 68.78.

- MeMurran. M. & Vim. T. (2004). Motivuing offenders to change in therapy: An orga. nixing framework. Legal Cr C.riminelegseal Psychology, 9(2), 295.311.

- Vallerand. & BUY:innate. R. (1992). Intrinsic. Extrinak. and Aremeivamonal Styles asPredictors of Behavior: A Prospective Sandy. ;mowed ego…sulky. 60(3). 599-620

- Millet, W. R, & Rollie!, S. (2002). Meer…enema! Intessommeg • Prepanys Propir Omer (2 ed.). New York. NY: Guilford Press.

- Burke. B. L. Dunn. C. W. Atkins. D. Cr.& Phelps.). S. R004y The Emerging Evidence Batt for Motivational Interviewing: A Meta.Analytic and Ii…mheative Inquiry journal of Copious Psychotharapy, 19(4).309-322.

- Moyers. T. B.. & Martin. T. (2006). Therapist Maumee on client language during moron. tional interviewing =nom. Jamul seSnismace Bee. Truniscu. 30(3). 245.251

- Anarhein. P. C. (2004). How Does Mocineional Internening Work Whin Client Talk Fan,III-Jas:’,./4.C41.49a4Pn.h.h…rA 13(4).323-316.

- Rua& B.. & Bogue. B. (2006). dodder Probation Offleer Tnensing Needs Analyka & COM. SINES CW1i014(.1,1 pair RICONINSMIALliM Causedfrom Agency Takt Kranwidgc. Boulder. CO: Justice System Assessment & Training.

- Turnan. F. S. (1999). Unraveling ‘What Works- for offenders in substance abaft unto mem services. Notional Drag Conn Inkinat Renew. 2(2).93-134.

- Tuman. F. S. (1999). Proactity Supervision: Supervision as Crime Prevention The Jamul ofOffender Monitoring(Spring).

- Timm C (1995). The !Input of Differen. Supervision Practices in Community Correa. tiona: Cause for Optimism. Aastralian And Nen Zminne foamed eCrinsneelov. 29. 2946.

- Bogue. B.. Vanderbilt. R.. & Ehmt. B. (2006). Canon:Mem CSSD RenUomn Report 11 for Sampler Year I ar.d Yem 2 (AsisslaWesin. .&ld. CT: Connection judicial &and,. Court Support Services Division.

- Walters. S. T.. Clark M. D. Gingerick. IL& Malcom M. L (2007). Almilarmg Offordem or Menges A Guidelo ‘Probation and Paran National lrattinue of Corrections Infonnaton Center.

- Burrell. W. D. (2008). Cognitive Behavioral Tactic. The Near Phase for E.-Atm.-8mA Practices. Commonly Cemeemont Report. 13(2).

- Williams. C. & Garland. A. (2002). Identifying and Challenging unhdpful dsinkiny A Menem in Psydnamie Treatment, 8.377.386

- Williams. C. & Garand. A. (2002). A cognitive.behrettual therapy assessment model for use in everyday clinical practice. Advancer in Pookacric Truancy:. 8(3). 172-179.

- Bogue. B. M.. Nandi. A.. &Rivera. A. E (2003). The Pn4thaY aniPa,41: Tmmest Planner. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sore, Inc.

- Ram D.. Naoom. S. F. Blase. K. A- Friedman. R. M.. & Wallace. F. (2005). higdonneor.non Ramreln Synthesis .fthe Litman, Tampa. FL: University ofBouth Florida. Lours 4C la Putt Florida Mental Health Bunny, The National Implementation Research Network (FM HI Publication Y231).

- Joe. G. W.. Broome. K. M.. Simpson. D- & Rowan-5:4G. A. (2007). Counselor perceptions of organisational fumes and OIDOntiOrtS training =penances. Jeanne( 4 &dn.’, Awe Treatment, 33(2).171.182.

- Rua& B.. Bogue. B. M.. & Diebel. J. (2007. Training & Coaching: In for a Penny. In for a Pound Offender Prognosis Report, 10(6).2.

- Joyce. B.. & Shower, B. (2002). Sondem Achievement Arne SesiDendepnens (3rd ed.). Alexandria. VA: Assulation for Supervision lad CO7i1:611111Devekfment.

Brad Bogue is the President of JSAT, Inc., a criminal justice consulting firm in Boulder, Colorado.

Jennifer Diebel is the Business Manager at JSAT, Inc. in Boulder, Colorado.

Tom O’Connor is the Administrator of Religious Services with the Oregon Department of Corrections