Home For Good in Oregon

A Community, Faith, and State Re-entry Partnership to Increase Restorative Justice

By Thomas P. O’Connor, Tim Cayton, Scott Taylor, Rick McKenna and Norm Monroe

Originally published Corrections Today, October 2004

Faith-based prison initiatives, from the White House Several years ago, the Oregon DOC articulated and down, are the subject of considerable public attention and heated debate. Some people truly believe, others are skeptical and some are just curious about the potential power of faith-based programs to change lives. Still others are deeply concerned that such programs will lead to an unconstitutional blurring of church and state boundaries or to the establishment of religion (i.e., favoring religious people over nonreligious people or those of one faith over another).1 And while the debate rages on, 650,000 inmates are being released each year back to America’s communities.

Historically, religion has played an important but changing role in the criminal justice system and is undergoing yet another period of evaluation and adjustment as the corrections field responds to several new religious and cultural trends in the United States.2 These trends include: an emerging differentiation of spirituality from religion, an increasing diversity of religious practice in the United States, a growing body of research into the impact of religion on offenders3 and a political openness to an increased role for faith-based programs in government efforts to solve social and budget problems. Recognizing the reality of these religious and social developments, Religious Services, which is based in the Transitional Services Division of the Oregon Department of Corrections, set out to develop a statewide community and faith-based re-entry program that would appropriately address constitutional concerns by not favoring any particular religion and by valuing the unique and distinct roles of church and state in preventing crime and fostering justice. The result is the Home for Good project.

Several years ago, the Oregon DOC articulated and began to implement a six-part model of best correctional practices called the Oregon Accountability Model (OAM) which emphasizes:

- The systematic assessment of criminogenic risk, need and responsivity factors, and the development of a correctional plan to address those factors for all inmates entering Oregon’s prison system;

- Positive staff-inmate interactions at all levels of the incarceration/release process that enhance offender motivation for change and role-model pro-social behaviors;

- A system of evidence-based work and treatment programs that make an individual’s incarceration experience both meaningful and corrective;

- The importance of working with the children and families of inmates in order to break the intergenerational cycle of crime;

- Re-entry preparation and planning from the first day of incarceration; and

- A seamless transition of inmates to the DOC’s community corrections partners in each of Oregon’s 36 counties, which enables offenders to continue working on their correctional plans and be successful in the community.

The Religious Services team of 26 full-time chaplains, volunteer program staff and support staff worked to support and foster OAM. However, the team knew that inmates needed help to continue developing their spirituality beyond the period of incarceration, and they knew that the churches, synagogues, mosques, etc., of Oregon would help in that process. As a result, Religious Services shifted one of its chaplain positions from a focus on the prisons to a focus on the community, and hired Oregon’s first full-time re-entry chaplain. During the past 18 months, this chaplain’s work in the community has allowed the Religious Services team to realize a long-term dream — the creation of a statewide community and faith-based re-entry project that provides a new focus on the re-entry component of OAM.

The Starting Point: Religion And Spirituality in Oregon’s Prisons

Paid state chaplains, and volunteer and support staff, along with more than 1,300 volunteers from a wide variety of religious traditions, facilitate an array of faith-based, in-prison services in a manner that has consistently been upheld by both state and federal courts to be constitutional. By definition, professional chaplains are trained to work with all faith groups, as well as people who do not belong to any religious group. A minister, pastor or rabbi is responsible for the members of his or her own religious tradition, but chaplains, who tend to work in the armed services, hospitals, hospice programs and prisons, serve all people regardless of their religious tradition. If this model of chaplaincy could work in the prisons, the Oregon DOC and Religious Services reasoned that a similar model could work in the community.

Fifty-two percent (8,646 out of 16,365 inmates in the system during a one-year period) of Oregon’s state prison population is active in religious and spiritual practices across a wide variety of religious faith traditions (Protestant, Catholic, Native American, Mormon, Buddhist, Earth-based, Jewish, Muslim and Jehovah’s Witness, among others). In addition to this involvement, many of the inmates who are not formally involved in a particular religious service have an active spiritual and prayer life or have direct contact with the chaplains through services such as grief counseling, serious illness/death notifications and hospice care. Further evidence of the pervasive role of spirituality in the lives of inmates comes from a Correctional Service Canada survey that found that 91 percent of male inmates and 87 percent of female inmates said they

would like to avail themselves of faith-based help in the community during their re-entry process.4 The task, therefore, was to facilitate the continuation of this broad-based, in-prison religious and spiritual involvement upon release, in a way that would help offenders further their spiritual growth, desist from crime and make the public safer.

Religious Services rooted the project in a theory that believes there is a unique role that community organizations, churches, synagogues, mosques, etc., can play in an evidenced-based correctional process that augments the role of criminal justice agencies. Each faith and community group has its own unique language, tradition, teaching, set of pro-social attitudes, beliefs and values, and an already established sense of community, and it can bring these resources to augment, partner with and enhance U.S. correctional systems. On the other hand, faith-based organizations, by definition, are neither prepared nor equipped to do the specialized work of holding offenders accountable and preventing recidivism upon release. This means a structured partnership with the justice system is necessary if they are to be of help. Four principles have helped this partnership to flourish.

Focus on the Community, Not the Offender.

The community is the real “client” of the Home for Good project. While more traditional approaches to reintegrating released offenders focus on the offenders and their needs, the goal of Religious Services is to increase the capacity of Oregon’s communities to address issues of justice and safety within their own neighborhoods, including the reintegration of offenders. In other words, a community justice rather than an individual needs-based approach5 is taken.

During 2002

Use Asset-Based Community Development.

While important aspects of a successful return to the community from prison are helping ex-inmates meet their employment, medical, mental health, substance abuse, housing, clothing, food and other needs, a more long-term and community-based response to the growing number of releasing offenders is to build the social and spiritual capacity of local communities to welcome, accept and reintegrate these returnees into the formal and informal structures of the community. Drawing on the work of professors John Kretzmann and John McKnight6 of Northwestern University, this project uses asset-based community development to help recognize and further develop the networking, community, and resource knowledge and strengths that churches, synagogues, mosques and community organizations bring to the task of helping ex-inmates reintegrate themselves back into their communities.

Know the Community.

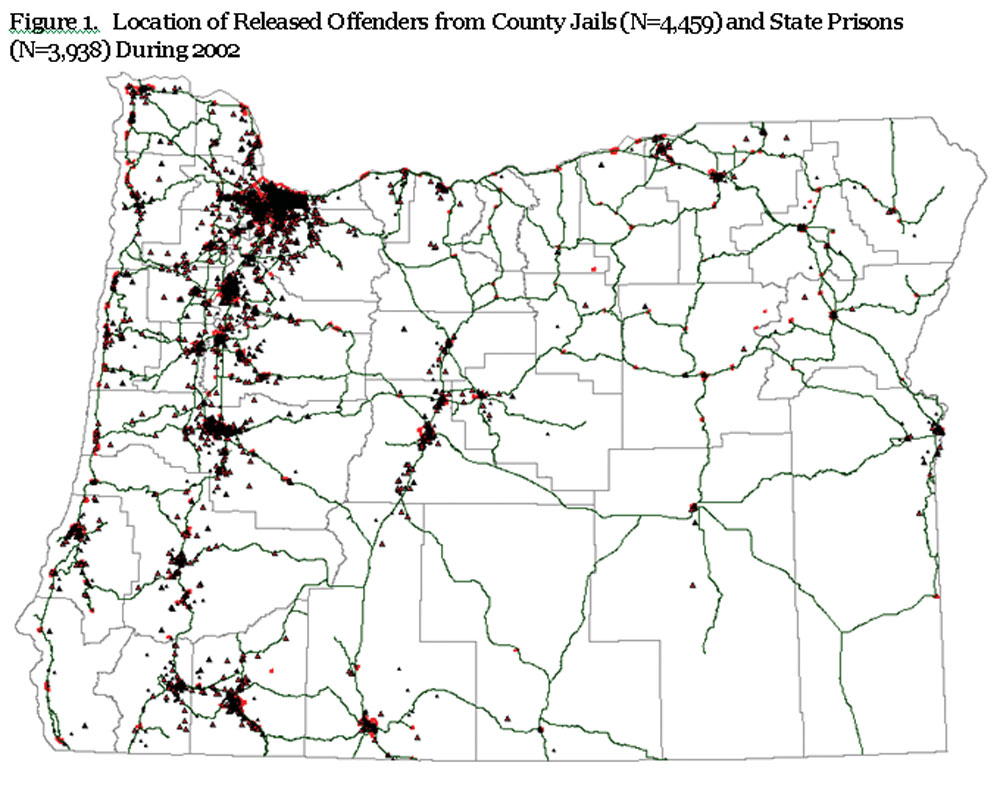

To assess the extent to which communities in Oregon were affected by issues of crime and community justice, Geographical Information Systems technology was used to map the neighborhood release location for all offenders returning from state prisons and county jails. Figure 1 shows the statewide pattern of releases for the year 2002.

The mapping reveals that the more densely populated Western Willamette Valley region, particularly the Northwestern Portland-Metropolitan area, accounts for the majority of releases. In Oregon, offenders are required to return to the county in which they lived at the time of their conviction, so the dark areas on the map are also the highest crime and arresting areas. Several of the neighborhoods in these highly populated areas show a far higher than average per capita rate of people returning from the jails and prisons to those communities. Preliminary analysis of crime rates in neighborhoods with very high rates of coercive mobility (a constant flux of removing and returning people to the community because of incarceration) suggest that these high rates of removal and return may contribute to social disorganization by disrupting the economic, social and cultural fabric of the community, thereby raising rather than lowering rates of crime in those communities.7 This map indicates that project staff need to work with different communities in different ways because their strengths and needs differ.

Use Evidence-Based Approaches to Preventing Recidivism.

Because two of the biggest risk factors for recidivism are a person’s antisocial associates and antisocial set of attitudes, beliefs and values, Home for Good has focused on creating community and faith-based partnerships that encourage releasing offenders to connect with and learn from the pro-social associates and the sets of pro-social attitudes, beliefs and values that are already successfully role modeled in the various faith traditions and communities the re-entry program is partnering with. Partners are encouraged and trained to understand the criminogenic risks and needs of returning offenders, and use the language and practices of their particular tradition to role model pro-social skills and attitudes in the area of work, family, education and citizenship. The re-entry program helps people realize that giving offenders a chance to witness, learn from and practice these skills and attitudes is crucial for preventing recidivism, even more crucial perhaps than giving people food, clothing, shelter, education and work. In other words, learning how to interact in a pro-social way with pro-social people and communities enables offenders to access the employment, housing, family and sobriety resources of that community in a more self-motivated, real, efficacious and concrete way. With these four principles in mind, a six-part structure for the Home for Good project was developed, which allows for the implementation of the statewide re-entry project in a systematic way.

Organizational Structure

A steering committee of 30 to 35 members with representation from all regions of the state was formed. The committee has among its leadership a former state representative, a former high-level manager of community corrections (probation and parole), a former staff member of the board of commissioners of Oregon’s most populated county, representatives of various state departments, recognized community and faith-based leaders, and representatives of community and faith-based organizations. The committee meets monthly, through video technology, at three major sites throughout the state as well as through phone links to more remote locations. This allows individuals from all parts of the state to have a voice in determining Home for Good’s direction.

The statewide steering committee has allowed the reentry program to develop a wide range of formal and informal partnerships with local community and faith-based groups. In some instances, staff help to mobilize the faith groups, while in other instances, their conversation centers on how Home for Good can support and enhance the work around justice issues already under way in local communities. Critical to this effort is the building of close and appropriate working relationships with county community corrections (probation and parole). In Oregon, each county runs its own community corrections department, which is responsible for the supervision of offenders on probation, parole and post-prison in their communities.

Fundamental to the organizational structure of Home for Good is a growing network of community chaplains and organizations representing each local community. Drawing from the experience of Correctional Service Canada, where more than 52 percent of all offender chaplaincy services are based in the community through a network of paid community chaplains, it was decided that a network of community chaplains and organizations (most of whom are volunteers) be built. The goal is to have one or more community chaplains for each of Oregon’s 36 counties.

The community chaplain makes links between all of the community and faith-based organizations in his or her area that are willing to work on issues of community justice and offender re-entry, provides them with training and promotes the coordination of their efforts.

As part of OAM’s focus on re-entry, seven of Oregon’s 13 prisons are now designated as “releasing institutions.” Home for Good is identifying volunteer re-entry coordinators to work in these re-entry prisons. The re-entry coordinators, under the supervision of the institutional chaplain, meet with inmates prior to release and help them develop the community and faith-based aspects of their release plans. Re-entry coordinators know or have access to the resources in the community, through the community chaplains in each county, and they work cooperatively with transition counselors in the institutions and probation and parole officers to help individuals prepare for their reintegration with family and community.

Applying the criminal risk principle to re-entry means developing different approaches to helping high-, medium- and low-risk offenders successfully reintegrate themselves and avoid recidivism. The “what works” research has shown that intensive programming for low-risk returnees increases rather than decreases their level of recidivism, while appropriately intensive programming for high-risk offenders reduces their rates of recidivism by 30 percent or more.8 To help address the demands high-risk offenders make on all correctional and justice systems, project staff are experimenting with a program called COSA (Circles of Support and Accountability).

Correctional Service Canada developed COSA and has had great success with it during the past 10 years. COSA comprises five to seven highly trained community volunteers who provide transitional support and behavioral accountability to high-risk offenders who voluntarily agree to be the core member of a COSA circle in their community. The circle members meet once a week with the offender, and one member of the circle calls or meets with the core member each day for the critical first year following release. The circle members are trained in the dynamics of criminality and how to provide a system of support and accountability that differs from, but augments, any correctional treatment or supervision provided by corrections professionals.

The project has developed several critical databases to support the work such as a list of faith-based resources that range from a congregation willing to welcome a released offender to faith-based transitional housing and drug and alcohol programs. Another database contains information on the criminogenic risks and needs and the correctional plan that a releasing offender can consent to share with his or her re-entry coordinators and community chaplains. An information system for voluntarily tracking the participation of returnees in the community and faith-based programs is also being developed. The goal is to use this data to evaluate Home for Good and determine whether the various components of the project have helped releasing offenders stay home for good.

Continued Success

Because of the early success and overwhelming positive response of the community to this project, the Oregon DOC believes the project has enormous potential to contribute to the capacity of communities to increase justice, reintegrate offenders and reduce recidivism. To date, the greatest challenge has been keeping up with the momentum and energy of the project with the very small staff and financial resources that have been devoted to the project.

There are dangers to this project, however. Involving community and faith-based volunteers with releasing offenders raises issues of manipulation, safety and security. Therefore, it is critical to provide proper training, support and information to volunteers. Another danger is that of favoring one religion over another or favoring religious over nonreligious individuals in a way that violates constitutional standards. Religious Services intends to avoid those dangers, however, by ensuring that the community and faith-based partners are closely connected with the Oregon DOC and community corrections and that their work is appropriately integrated into the evidence-based principles of effective correctional practices.

ENDNOTES

- Cooperman, A. 2004. An infusion of religious funds in Florida prison: Church outreach seeks to rehabilitate inmates. Washington Post, 25 April, page A1.

- O’Connor, T.P. 2003. A sociological and hermeneutical study of the influence of religion on the rehabilitation of inmates. Unpublished manuscript.

- O’Connor, T.P. and N. Pallone (eds.). 2003. Religion, the community, and the rehabilitation of criminal offenders. Binghamton, N.Y.: Haworth Press.

- Correctional Service Canada. 2003. National chaplaincy evaluation: Pastoral care draft report. Ottawa.

- Karp, D.R and T.R. Clear (eds.). 2002. What is community justice: Case studies of restorative justice and community supervision. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Sage Publications.

- Kretzmann, J.P. and J.L. McKnight. 1993. Building communities from the inside out: A path toward finding and mobilizing a community’s assets. Chicago: ACTA Publications.

- Clear, T.R., D.R. Rose, E. Waring and K. Scully. 2003. Coercive mobility and crime: A preliminary examination of concentrated incarceration and social disorganization. Justice Quarterly, 20(1):33-64.

- Andrews, D.A., I. Zinger, R.D. Hoge, J. Bonta, P. Gendreau and F.T. Cullen. 1990. Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28(3):369-404.

- McGuire, J. 2002. Evidence-based programming today. Paper presented at the International Community Corrections Association Annual Conference, 5 Nov., Boston.

About the Authors

Thomas P. O’Connor, Ph.D., is administrator of Religious Services for the Oregon Department of Corrections. The Rev. Tim Cayton, D.Min., is chaplain, Religious Services, Oregon Department of Corrections. Scott Taylor is chief, Community Corrections, Oregon Department of Corrections. Rick McKenna is a consultant for Correctional Service Inc. and a steering committee volunteer. Norm Monroe is vice president for community development, Cascadia Drug and Alcohol Treatment Program, and a steering committee volunteer.