Prison Religion in Action and its Influence on Offender Rehabilitation

O’Connor, T. P., & Perreyclear, M. (2002). Prison Religion in Action and its Influence on Offender Rehabilitation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, Volume 35(3/4), 11-33.

© 2002 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved

Prison Religion in Action and Its Influence on Offender Rehabilitation

THOMAS P. O’CONNOR

Oregon Department of, Corrections

MICHAEL PERREYCLEAR

Center for Social Research, Silver Spring, Maryland

SUMMARY

A theory of religious conversion, social attachment, and social learning guides this study of prison religion and its influence on the rehabilitation of adult male offenders. The study found the religious involvement of inmates in a large medium/maximum security prison in South Carolina was extremely varied and extensive. During a one-year period 49% of the incarcerated men (779 out of 1,579) attended at least one religious service or program. Over 800 religious services or meetings, across many different denominations and religious groups, were held during the year. Two prison chaplains, four in-mate religious clerks and 232 volunteers who donated about 21,316 hours of work to the prison (the equivalent of 11 full-time paid positions) made this high level of programming possible. The estimated yearly cost of these religious services was inexpensive at between $150 to $250 per inmate served; in contrast, other effective correctional programs cost around $14,000 per person. Controlling for a number of demographic and criminal history risk factors, logistic regression found an inverse relationship between intensity of religious involvement and the presence or absence of in-prison infractions. As religious involvement increased the number of inmates with infractions decreased. The findings of the study provide greater insight into the nature of religion in prison setting and support the view that religion can be an important factor in the process of offender rehabilitation.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-HAWORTH. E-mail address: <getinfo@haworthpressinc.com>Website: <hapillwww.HaworthPress.corn> © 2002 by The Haworth Press, Inc. All rights reserved.]

KEYWORDS

Religious conversion, social attachment, social learning, prison religion, offender rehabilitation

There is a deeply held belief among many in the ‘U.S. that religion plays a profound and necessary role in the creation and maintenance of a moral and law-abiding community. Indeed this kind of belief in the social effects of religious practice has inspired a great deal of religiously motivated social action aimed at rehabilitating criminals in the U.S. and was influential in the very creation of the U.S. prison system (Colson, 1979; Colson & Van Ness, 1988; McKelvey, 1977; O’Connor & Parikh, 1998; Skotnicki, 1992). This study takes that belief in the efficacy of religion seriously and examines the influence of prison religion on the rehabilitation of adult prison inmates. Is there, in fact, a relationship between religion and the rehabilitation of prisoners and what is the nature of that relationship?

There is no doubt that religion is widely practiced among the nearly two million prisoners in the U.S. Almost every prison has a chaplain who presides over the constitutional right of incarcerated people to practice their religion, and a 1991 survey found that about one out of every three inmates (32%) participate in worship services, Bible study groups and other religious activities, making religious involvement one of the most common forms of “programming ” in U.S. state prisons (U.S. Department of Justice, 1993). Despite the extensive historical influence and widespread practice of religion in prisons, very little research of good methodological quality has been done on the meaning and practice of religion in prison, or on whether that religious practice actually contributes to the rehabilitation of offenders. Reviews of the criminological literature point out that while a substantive body of work has been published on the influence of religion on the level of crime in the general population, especially among juveniles, there has been little published that directly concerns the influence of religion on the rehabilitation of inmates or ex-offenders, especially among adults (Clear et al., 1992; Gartner et al., 1990; Johnson, 1984; Sumter & Clear, 1998).

In general, the reviews of the broader literature on religion and the prevalence of crime in the general community conclude that while most studies have found a significant inverse relationship between religious involvement and crime, the methodological weaknesses of these studies tend to make their findings somewhat inconclusive (Baier, 2001; Ellis. 1985; Evans, Cullen, Dunaway, & Burton, 1995; Gartner, Larson, & Allen, 1991; Knudten & Knudten, 1971; Sloane & Potvin, 1986; Tittle & Welch, 1983). For example, Sumter (1998, 30) found that 18 of 23 studies published since 1985 produced evidence of an inverse relationship between different measures of religiosity and various indicators of deviance but summarized her findings in the following way:

Although associations have been detected, the studies have not been successful in establishing evidence of causal relations between these measures which primarily results from two inherent problems (research design and measurement error) and other methodological flaws in studying religiosity and deviance.

The few studies that have looked directly at the influence of religion on adult offender rehabilitation tend to follow the same pattern as the wider body of literature—some evidence of a significant relationship between religious involvement and rehabilitation, accompanied by methodological weaknesses that leave unanswered questions and inconclusive findings. These studies of the influence of religion on adult offender re-habilitation all tended to use either in-prison infractions or recidivism as their measure of rehabilitation. Three studies have provided evidence of a positive relationship between religion and offender rehabilitation, two studies failed to find evidence of such a relationship, and one yielded mixed evidence.

RELATED STUDIES

Johnson (1984) found neither a significant correlation nor relationship in a path analysis between self-reported religiosity, church attendance, or prison chaplain’s rating of inmate religiosity and amount of time spent in confinement for disciplinary infractions (controlling for race, age, offense type, maximum sentence, denomination, and religious conversion) among 782 men in a minimum security prison who were serving their first term of incarceration. Young et al., however, did find a significant long-term impact of a Federal prison ministry program known as the Washington, DC Discipleship Seminars on adult criminal recidivism. These Seminars were sponsored and run by Prison Fellowship Ministries (PFM) which was founded in 1975 by Charles W. Colson, a former presidential aide to Richard M. Nixon, following his own incarceration in Federal prison on a conviction of obstructing justice. Young et al. identified 180 men and women who had participated in the seminars and used a stratified pro-portional probability sampling method to select a matched control group of 185 Federal inmates from a cohort of 2,289 inmates who were released around the same time as the PFM inmates. The two groups were carefully matched on age, race, gender, and Salient Factor Score (a risk index that is predictive of recidivism). The study examined the re-arrest patterns of the two groups over a period of eight to 14 years after each person’s release from prison. Logistic regression analyses with recidivism (yes or no) as the dependent variable, controlling for race, gender, age at release, risk level, and time on the street, showed that the PFM group had a significantly lower rate of recidivism.

Survival analysis also showed that the PFM group who did recidivate took significantly longer to recidivate compared to the comparison group recidivists. Further analyses revealed that most of the program effects were concentrated in PFM women (white and black) and in white PFM men who were in the low risk of recidivism category. Compared to their respective controls religious women had much lower rates of re-arrest than the religious men. No impact of the program could be discerned among white men in the high risk category or among black men across all risk categories. These findings indicate the importance of controlling for gender, race and risk factors when examining the influence of religion on offender rehabilitation. Beside the issue of self-selection or self-motivation, which affects all the studies on this topic because of the inability to randomly assign subjects to religious and non-religious groups, an important methodological weakness of this study lay in the fact that the subjects in the religious program group were selected for participation according to strict criteria. This meant that the PFM group could have succeeded because the basis on which they were selected rendered them prone to succeed rather than because of their participation in the program. However, the essence of the selection criteria was that the subjects be heavily involved in religious participation prior to the program. Thus the subjects in this study were highly involved in religious activity and it may be that the intensity of their religious involvement combined with the program was responsible for their success.

Clear and his co-investigators (1992, 1995) also found a significant relationship between religiosity and rehabilitation. Clear’s study used in-prison adjustment (a psychological measure of how well an inmate was able to cope with the deprivations and difficulties of prison life) and in-prison infractions as its measure of rehabilitation. Clear and his associates studied 769 men in 20 prisons across 12 states in the U.S. chosen to represent different regions of the country as well as different security levels of prisons. This was a non-random sample of subjects as each subject volunteered to be in the study. Clear et al. reasoned that religion might interact with other personal and situational variables within the prison context to affect in-prison adjustment as well as in-prison infractions. Religiosity was measured using a self-report instrument that included 33 questions from the Hunt and King scale (a measure of religious beliefs through assessing symbolic religious commitment) and a set of 12 questions about what the inmates would do in different prison situations of conflict. The subjects also answered questions on depression, self-mastery, self-esteem, demographics and criminal histories. In-prison adjustment was measured using the Wright (1985) adjustment scale. Infractions were measured by the self-reported number of disciplinary infractions. Although adjustment and infractions scores were significantly correlated with each other, analysis showed that these two variables were measuring different constructs.

Clear et al. found strong significant correlations between high religiosity and both adjustment and infractions at a bivariate level. Controlling for demographic and criminal history variables ordinary least squares regression revealed that high religiosity directly predicted fewer infractions and indirectly predicted better adjustment. Religiosity was one of the strongest predictors of the number of infractions along with variables like number of priors and age. Religiosity fell out of the regression equation on adjustment when the control variables were introduced, but was indirectly related to better adjustment through depression. Of particular interest is that the study findings were “prison specific”—the religious effects on adjustment and infractions were found in some but not all of the prisons. Furthermore, the two effects were not found together, but depending on the prison there was either a religious effect on adjustment or on infractions. Religious factors, therefore, can interact with other variables and produce different results. This means that context is a vitally important variable for the study of the relationship between religion and rehabilitation. A second study by Sumter (1999) using some of the data from the Clear et al. (1992) study found that a religious vs. non-religious dichotomy did not predict post-release success for the subjects. However, this study did find that the more motivated offenders were involved in religious activities in prison and the more they believed in a transcendent God, the less likely they were to be rearrested after release to the community.

A study by O’Connor, Yang, Ryan, Wright, and Parikh (1996) found that religious involvement had no relationship to the presence or absence of in-prison misconducts but had some relationship to recidivism. This study controlled for self-selection bias by using a multivariate matched sampling procedure to draw a one-to-one matched control group from over 40,000 inmates from the general population based on their propensity to self-select into the religious program. Over 200 men who had participated in a religious ministry program in four New York prisons did not differ from the matched comparison group on whether or not they had a prison misconduct. This study also compared the prison ministry and comparison groups on recidivism and found no overall difference between the two groups on whether or not they were rearrested or on time to rearrest. The study did, however, find some significant differences in recidivism, when it compared those who had high rates of ministry participation to those who had low or no ministry participation and controlled for level of risk of recidivism. A weakness in this study was the relatively small amount of information presented on the overall religious participation of the program group and the complete absence of information on the religious participation of the comparison groups. Because the study had no way of telling for sure that the comparison group was not involved in religious activities the study may even have been comparing religiously involved inmates to other religiously involved inmates.

A secondary analysis of the data from the O’Connor et al. study by Johnson, Larson, and Pitts (1997) was essentially confirmatory and also found no evidence of a significant overall difference between Prison Fellowship participants and “non-religious ” controls on either in-prison in-fraction or rearrest within one year. The Johnson group did find some evidence of a significant relationship between high program attendance and lower rates of recidivism.

Pass (1999) did not find any influence of self-reported religiosity on in-prison infractions among 345 randomly selected inmates from the prison population at Eastern Correctional Facility in New York. Subjects were asked about their agreement or disagreement with three statements: (1) Religion is important; (2) Religion gives people special privileges; and (3) Some people in religious groups joined for protection. Pass also used a 10-item “Intrinsic Religious Motivation Scale” (Hoge, 1972) to measure religious motivations. The motivation scale seeks to measure how much a person’s religiosity is motivated by internal reasons (using religion to find meaning in life) or external reasons (using religion to develop social relationships) (Hoge, 1972). Pass hypothesized that only internalized religion would lead to a reduction of in-prison infractions.

Pass found that a higher number of people reported a religious affiliation since prison than before prison and fully one-third of the sample reported a change of affiliation once in prison. Using ANOVA, Pass also found that religious motivation scores differed significantly among the religious groups. Muslims were the most internally religiously motivated, followed by Protestants, Other religionists, Catholics, and those with No religion. Logistic regression revealed that levels of internal motivation were not significantly related to the presence or absence of infractions within a three-month period prior to the survey when religious affiliation, importance of religion, views on protection and privilege, race, age, educational level, and first offender versus multiple offender status were controlled for.

Each of the foregoing studies has strengths and weaknesses. As a group, the studies have helped us to understand more about the nature and impact of prison religion. Prison religion varies in its meaning and practice across individuals, prisons, and different religious groups. Intensity of involvement (or “dosage ” in treatment jargon) seems to be a crucial factor in whether or not it has an impact on offender rehabilitation. Furthermore, other variables such as gender, race, risk level for recidivism, and prison context influence both the kind and depth of impact that religion may have on rehabilitation. Certain things are needed to make these intimations of how religion “works” more conclusive: future studies need to be more informed by theoretical considerations, become more precise in their measurements of religion, and model the impact of religion on rehabilitation using better research designs and statistical methods.

The present study seeks to build upon the knowledge gained in previous studies of religion and offender rehabilitation by overcoming many of the methodological difficulties that rendered their findings somewhat inconclusive. The study sought to determine whether level of religious involvement influenced rehabilitation as measured by in-prison infraction. The setting was Lieber Correctional Institution (Lieber), a large medium/maximum security prison for men in South Carolina. During 1996, we worked with the South Carolina Department of Corrections (SCDC) Research division, the Pastoral Care division, and the chaplain’s office at Lieber Correctional Institute (LCI) to collect sign-up sheets for every religious activity that occurred in the prison. The chaplains and their clerks at Lieber prison entered this data into a computerized system that maintained a count of times each person attended any religious program by month. In addition, they recorded what activities were held on what dates of every month. (There may be some minor errors in the data, because inmates did not always sign in when they attended programs, and occasionally volunteer program leaders failed to turn in sign-in sheets. But chaplains and their clerks made every effort to monitor the data, and we feel satisfied that the data adequately represent the actual attendance of inmates at religious programming.)

The SCDC Division for Resource and Information Management then provided us with additional demographic, criminal history and infraction data on all 1597 inmates who spent any part of 1996 in LCI. (Many who do not attend services may nonetheless be “religious” persons; hence, this study is not a study of religiousness per se but instead of religious involvement.) This was the entire population of inmates at Lieber in 1996 and included both those inmates who had and who had not attended religious programs Confidentiality was maintained by using the data in aggregate form only. This design for collecting data meant that there was no “selection bias” in our data, since participation was voluntary. Selection, after inmates had volunteered, proceeded without specific criteria. Because there was nothing resembling either “random selection” or “random assignment” into “religious” or “non-religious” groups once inmates had volunteered to participate, we nonetheless need to recognize the likely link between self-selection and motivation.

GUIDING THEORY

The theory underlying the study is based on a theological understanding of religious conversion and faith development (Fowler, 1981; Lonergan, 1972) and a criminological understanding of how rehabilitation comes about through a process of social attachment (Sampson & Laub, 1993) and social learning (Andrews, 1995; Bandura, 1977). The theory of religious conversion holds that we are spiritual beings as well as physical, emotional, social, and intellectual beings. Our spiritual nature means that we are capable and desirous of having an ultimate and meaningful sense of connectedness or relationship with other people, our world, and God. The extent to which we have not fully achieved this connection or union is the extent to which we are in need of religious conversion or development. Saint Paul gives us a Christian understanding of the source of religious conversion when he says “The love of God has been poured out in our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us” (Rm:5:5). Just as a parent’s love awakens life within a child, God’s free gift of love is constantly awakening and deepening life within us. From this perspective spirituality is the integrative principle of our lives. One inmate at Lieber prison involved in religious programming seems to be referring to this sense of spiritual conversion or awakening when he says: “Before [prison], it was all me. Now I know life is also about relationships. I have to think of others and God. If you’re serious about God, you have to take on the nature of God, and God cares about other people too.” The lack of a spirituality was expressed by another inmate who was not religiously involved when he insisted: “Life is dog eat dog, and I will do anything I have to—lie, cheat, steal, or kill—to stay out of here [prison} when I get out.” Religious faith and belief can free up a part of who we are, and these inner resources can lead to changed attitudes and behaviors.

Social attachment theory holds that the more attached a person is to the major social institutions of life (family, education, work, politics and religion), the less likely he or she is to commit crime, for he or she has something of value to lose by committing crime. Social learning theory believes that criminal behaviors are learned behaviors in a given social and cultural context. Because criminal behaviors are learned behaviors, offenders are capable of learning noncriminal behaviors should their given context change. Both of these processes—increased social attachment and new social learning—are likely to be accelerated when an inmate becomes immersed in the religious milieu of a prison, for this milieu places an inmate among chaplains and volunteers who are very attached to the major social institutions of life and who are very committed to pro-social learned behaviors. A national study of correctional chaplains found that 79% had a Master’s degree or higher. In addition, prison chaplains had an average of 10 years of correctional experience and believed strongly in a philosophy of rehabilitation. The chaplains spent most of their time counseling inmates and used methods of counseling that treatment studies have found to be effective in reducing recidivism. The chaplains were highly-skilled role models and advocates for inmates, and they were also responsible for coordinating the work of the thousands of religiously motivated volunteers who work in prisons (Sundt & Cullen, 1998).

An exploratory study in South Carolina surveyed 82 ministry volunteers and found they were moved to work in the prison system by two major motivations: (1) to act on their faith and (2) to make a difference. When the study compared these volunteers to the general population of the Southeast region, it found that the volunteers had the same gender and ethnicity demographics as the general population, but tended to be older. The volunteers were also more involved than the general population with the major social institutions of life. For example, the volunteers earned more, were more likely to be married (80% versus 54%), had more education (57% versus 23% had some college education), were more involved in politics (86% voted versus 64%), and 90% of the volunteers compared to 30% of the general population went to church once a week or more. The volunteers were also happier than the general population-47% versus 31% “very happy” (O’Connor, Parikh, & Ryan, 1997). In other words, the volunteers were a group of people who had learned how to successfully negotiate and derive satisfaction from the different worlds of work, family, education, politics, and religion. In contrast, offenders tend to have trouble negotiating these areas of life, and we know that problems in these areas are predictive of crime and recidivism. One inmate explained how the modeling of religious volunteers (some of whom were successful ex-offenders) provided him with hope by their example of overcoming adversity:

I have to come to my own place of healing… I’ve seen myself do some things, or think some things, or say some things, or act in a manner that I know was inappropriate. And still it makes me unhappy. And so, the question still comes to me, why did I do that? So what do they [the volunteers] do? The hope, the hope says that these people [the volunteers] have changed their lives, and if they can do that so can I. The chaplains and volunteers are a tremendous resource as role models and teachers of the very skills and lifestyles that many offenders lack but desire. It seems natural and theoretically valid from a “what works ” correctional treatment point of view to hypothesize that the social attachment and learning which takes place between the chaplains, volunteers and offenders in each area of life, not only in the religious domain, is likely to aid the process of offender rehabilitation. Awakening the religious or spiritual domain in a person brings additional inner hope, motivation, and resources for learning how to address the domains of work, family, education, church and politics in a pro-social manner. Thus our hypothesis for the study was: The greater the level of religious involvement, the greater the influence of religion on the rehabilitation of adult offenders as measured by in-prison infractions.

NATURE AND PRACTICE OF PRISON RELIGION AT LIEBER

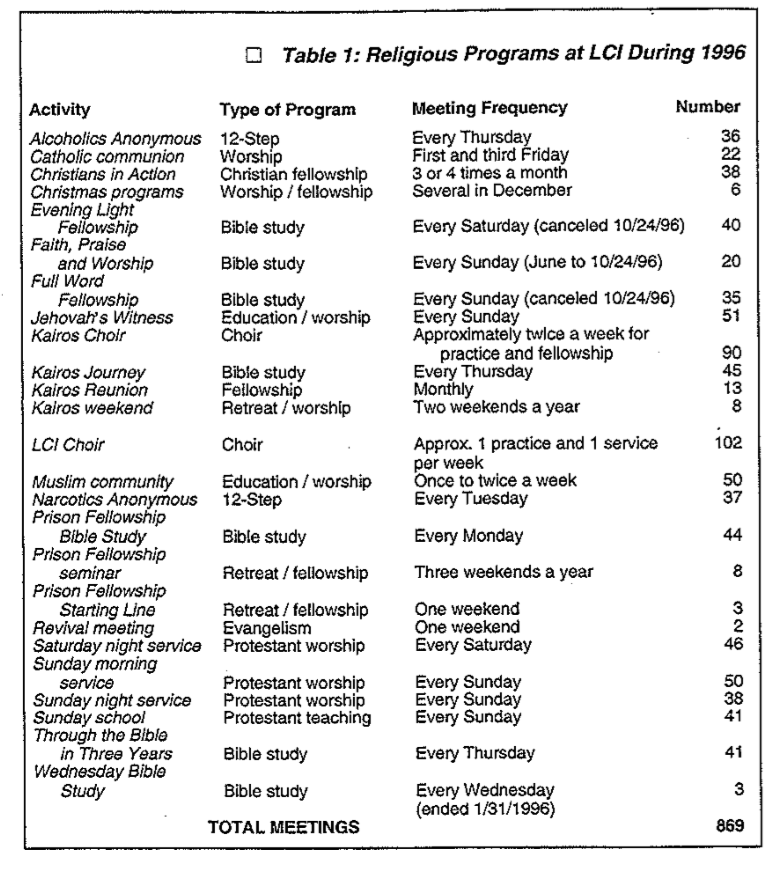

During the course of 1996 the chaplain’s office recorded 23 different kinds of religious programming at LCI, most of them offered on a weekly basis. These programs include worship services, Bible studies, religious seminars and retreats, alcoholics and narcotics anonymous, and fellowship gatherings. The religious services are offered by many different denominations or church groups such as Catholics, Protestants, and Muslims. Volunteers from outside the prison lead the majority of the programs, while a few are run by the chaplain’s office or by inmates themselves. There is a religious program of some kind offered every day of the week. Table 1 lists these religious activities, their general type, the frequency of their meetings, and the total number of meetings held in 1996.

Many of these religious programs attract a similar group of attendees, while a few are notably distinct. Using data from the month of July, those who attended Alcoholics Anonymous were highly likely to also attend Narcotics Anonymous, but both groups were less likely to attend any other religious programming. The Muslim community also tended to be a separate group unto themselves, as did the Jehovah’s Witness attendees and Catholics.

During the year, 779 of the 1,597 inmates-49%–attended at least one religious program or service. This is a very high level of religious involvement given that the estimated average attendance at religious services in state prisons throughout the country is only 32% (U.S. Department of Justice, 1993). The fact that Lieber prison is located in the “Bible Belt,” a highly churched region of the U.S., probably helps to explain this high level of inmate attendance, together with the fact that the religious program at Lieber seems to be well organized.

Of the total 779 inmates who attended any religious programming, 12% participated mostly in non-Protestant programs, while 88% participated mostly in the Protestant programs. Attendees at any of the Protestant worship services or Bible studies were likely to also attend other Protestant worship services or Bible studies. Using a cut-off correlation of .30 as an indication of a meaningful relationship, the weekend worship services showed relationships with the largest number of other programs and were most highly correlated to each other. That is, inmates who attended one worship service were likely to attend other worship services and also a Bible study or two during the week.

On average, those who went to religious services in Lieber went to about six meetings every month. (Since some of the men entered LCI after January 1996 and some left before December of the same year, not everyone had the same numeric opportunity to attend.) In all there were 23 different kinds of religious services or programs operating in the prison. Amazingly, there were more than two religious meetings every single day of the year (a total of 869 meetings). The fact that prison becomes almost like a monastic setting for some inmates can be discerned in a comment from Shawn, one of the inmates at Lieber:

I guess when I was out in the world… I was raised where I went to church, was in the church. The difference is out there I didn’t have the time to stop, think, study, get a chance to know who Jesus was, and what He was about. Whereas back here you got nothing but time.

The type of spiritual reflection taking place here seems to be about personal transformation or spirituality and not just rote religious attendance.

The religious activities at Lieber were made possible through the services of two full-time prison chaplains, four inmate clerks to the chaplains, several inmate religious leaders, and approximately 232 volunteers from the community. The 232 volunteers donated about 21,316 hours of work to the prison: the equivalent of 11 full-time paid positions. The estimated yearly cost of these religious services could be considered a bargain at about $150 to $250 per inmate served. In contrast, Joan Petersilia estimates that effective correctional programs cost about $14,000 per inmate per year (Petersilia, 1995). Thus, some of the main findings of this study are that religious and spiritual involvement in prison is extremely varied and extensive, and costs the Department of Corrections very little.

FINDINGS ON THE IMPACT OF RELIGION ON INFRACTIONS

When we compared the religious attendees to the non-religious attendees on their demographics and criminal histories, we found some interesting similarities and differences. There were no significant differences between the two groups on marital status, having children, or race. Thirty-five percent of the inmates reported that they had been or were married, over half (60%) reported having at least one child, with a range of 0 to 18, and an average of one, and the majority (68%) were Black, with virtually all of the rest being White. Nor were there any differences on the number of prior sex or violent convictions, the number of current offenses, or the number of current offenses which involved alcohol or drugs.

The religious and non-religious attending groups did differ significantly on the following variables. The religious attenders tended to be younger than the non-religious attenders with an average age of 33 compared to 34, and to be a little more educated with an average of 11 years of education compared to 10 (p < 05). The “religious” inmates had an average of five prior convictions, compared to an average of four for the “non-religious,” and were more likely both to have a current sex offense (24% versus 15%) and a current violent offense (61% versus 52%). These differences mean that the religious inmates were probably more in need of rehabilitation that the non-religious inmates, as they have more serious criminal histories. In other words, the religious programs were not “creaming” the easiest inmates to work with.

For a variety of reasons, such as new incarcerations, completion of sentences, changes in custody level, lockup, administrative needs, court hearings and parole, inmates are moved in and out of LCI regularly. Therefore, most of the inmates in our study did not spend the entire 365 days of 1996 in LCI. They averaged 230 days, with a range of 0 (full days) to 365. The religious inmates had been in LCI for a significantly longer part of 1996, averaging 276 days, while the rest of the inmates averaged 186 days. This probably means that the longer a man is in a particular prison, the more likely he is to attend religious programming or services at that prison, at least once or twice.

To look at the impact of religious programming, we needed to calculate a rate of attendance at religious programs. We wanted to be able to distinguish between those religious inmates who were highly involved and those who were not so highly involved in religious programs or services. The movement of inmates in and out of LCI and the varying number of religious sessions per month complicated calculating a reasonably accurate rate of attendance at religious programs. The rate needed to reflect the actual number of meetings attended divided by the number that could have possibly been attended during the time that individual was in LCI.

In addition, to look at the impact of the religious programming, we narrowed the window of opportunity to only the time period the person was in LCI following their first appearance at a religious program in 1996. We wanted to be sure that we were only considering infractions that took place after the men had been involved in religious programs. The number of days spent in Lieber was corrected for the “religious” inmates to reflect only the days in the institution since they first attended a religious program. (The estimate of days spent in the institution may be underestimated, because the starting date was measured only to the level of months rather than days. Thus, when a month was subtracted to account for a difference in the beginning of a program, 30 days were lost, when the real number may have been something less than that. However, such an underestimate is consistent across cases and is never more than 30 days.) Therefore, the religious participation rate is the number of religious sessions attended by an individual in 1996 at LCI, divided by the number they personally could have attended since their first appearance at a religious activity in 1996. (We estimated the number of meetings an inmate could possibly attend by adding the number of religious sessions per month from the first month he appeared at a religious meeting through his last month in the prison. The procedure somewhat overestimates, since the person may have had some movement in and out of LCI between their first and last month that prevented attendance, other activities or restrictions may have sometimes prevented attendance, and the first and last month may not have been full months for that person. Overestimating this value means that the rates of attendance may be somewhat below the most accurate value.) By definition, the participation rate of the inmates who did not attend any religious sessions is always zero.

An infraction is any incident of breaking of institution rules for which the inmate is caught and found guilty. It could be anything from assaulting someone, to being caught in a restricted area, to having contraband in one’s possession, to escaping. The majority of LCI inmates (78%) had no infractions in 1996. The mean number of infractions is 0.43, with a range of zero to 16. No escape infractions were reported. Only 1% of the inmates incurred an infraction that was classified as violent.

To analyze the impact of religious programming on infractions we took a two-tiered approach. First of all we examined whether a wide variety of variables had any relationship to predicting infractions taking each variable one at a time. As far as possible, given the data we had to work with, we used the literature on infractions and recidivism to guide us in selecting those variables that are known to be in some way related to predicting infractions (Alexander & Chapman, 1981; Andrews et al., 1990; Bailey, 1966; Law, 1993; Motiuk, 1983). Our question was: Does the extent of involvement in religious programming help to predict in-fractions in addition to other variables that predict infractions? The following characteristics were statistically unrelated to infractions at a bi-variate level: race, self-reported highest level of education completed, count of prior convictions, count of violent prior convictions, use of alcohol or drugs during the commission of a crime, having a current conviction on a sex offense, and having a prior conviction on a sex offense.

Eight non-religious characteristics were significantly related to whether or not a person had infractions. Inmates who had a current conviction on a violent offense were more likely to have an infraction (24%, compared to 18%). The same was true for inmates with any prior violent crime convictions (27%, compared to 20.6%). In addition, the more current convictions an inmate had, the more likely he was to have an infraction. Those who were either currently married or had been at one time were less likely to have an infraction than those who had never been married (13%, compared to 26%). The familial tie of having children was also important. Those with no children were more likely to have an infraction than those who had at least one child (26%, compared to 19%). Age had an inverse relationship with infractions—the older an inmate was, the less likely he was to have had an infraction. Also, the higher maximum sentence length an inmate had and the more days he spent in LCI in 1996, the more likely he was to have an infraction.

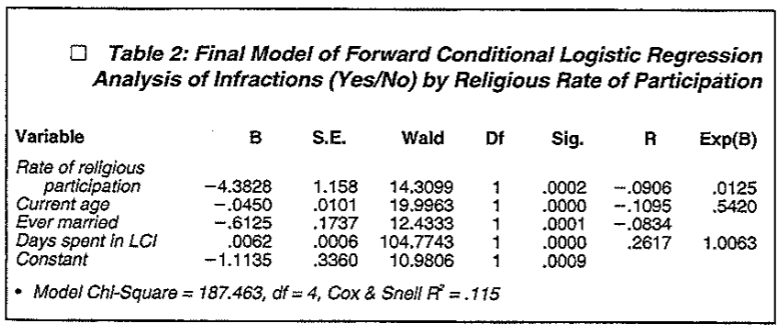

Finally, a bivariate analysis of religious involvement and infractions found two things. First, when religious inmates were compared to non-religious inmates, there was no difference in the propensity to have infractions. Secondly, when we looked at rates of participation in religious programming, higher rates were always associated with less chance of infractions. The more religious programming sessions an in-mate attended, the less his chance of having infractions. This gave us a clue to the fact that religious involvement had an impact on infractions. However, these results might be an artifact of the religious inmate’s different amounts of time in LCI than the non-religious inmates or to the fact that religious inmates were different from non-religious inmates in certain ways, as pointed out above. We needed to include these non-religious demographic and criminal history variables as controls for religious participation in a multivariate analysis. All items mentioned above, regardless of whether or not they were individually related to the presence of infractions, were included as possible controls in forward conditional logistic regression. We were particularly aware that we needed to control for the time spent in LCI in 1996, since there was a significant difference between the religious and non-religious groups on this important variable.

When we did this and compared all religiously involved inmates who attended any type of religious program to the non-religiously involved inmates, the independent variable did not reach statistical significance to enter the final logistic regression model. That is, there was no difference between the religious and non-religious groups in their likelihood of having an infraction.

However, we did find that the more religious sessions an inmate attended, the less likely he was to have an infraction. Thus, the findings supported our hypothesis. As previous studies have found, the intensity of religious programming seems to help reduce infractions. The impact of religious programming derives not from the fact of attending religious programs but from going to religious programs more often. In Table 2, the final logistic regression model shows that an inmate’s chance of committing an infraction goes down as his rate of attendance at any religious program goes up, within categories of current age, ever married, and days spent in LCI. What Table 2 tells us is that the more religious sessions the men attended the better the chance that they had no infractions.

Logistic regression enables one to say whether or not a variable of interest is related to a dichotomous dependent variable. However, logistic regression is not very helpful when it comes to interpreting the meaning of that relationship. To help us get a glimpse of what it means to say that the more often inmates attended religious programs the less infractions they had, we looked at the percentage of inmates who had little or no religious involvement and found that 21% of them had infractions during the study period. By way of contrast only 11% of those inmates who had a medium or a high level of involvement with religious programs had infractions during the study period. One must exercise caution in interpreting the meaning of these differences, for the model indicates that such a difference may be attributable to a number of variables, including rate of religious participation.

DISCUSSION

The two main findings of the present study are (1) religious practice in the Lieber prison setting was extensive, varied, and inexpensive to conduct; and (2) when a number of demographic and criminal history variables are controlled for, the intensity of religious practice was inversely related to the presence of in-prison infractions.

These findings expand the literature on religion in corrections by providing the first detailed empirical description of the actual practice of religion in a prison setting, and by deepening our understanding of the influence of religion on rehabilitation. Religious practice in prison can be very extensive with about 50% of inmates attending religious services an average of six times per month. Religious practices spread themselves across more spiritually-based programs such as AA and NA, and more formal religious programs such as worship and Jumuah services that are Protestant, Catholic and Muslim. Because of the heavy involvement of hundreds of volunteers in running these programs they cost as little as $150 to $250 per inmate per year to run. The presence of so many volunteers who gave over 21,000 hours of programming to the prison also means that religious programming is a major source of pro-social role modeling in the prison setting, for these volunteers appear to be very attached to and involved with the major social institutions of life—family, work, education, church and politics. The work of the chaplains, volunteers and religiously involved inmates insures that the life of faith or the spiritual dimension of life is brought into being in the prison setting. Religion may help to bring into the correctional setting the much-needed element of hope and motivation to change, and introduce important ethical and religious ideas of forgiveness and the love of one’s neighbor. The involvement of members of the “outside” community also helps to normalize the prison experience and ameliorates the sense of isolation from the community that incarceration brings. Isolating people from the community can actually cut off offenders from the pro-social sources of behavior and support they need to learn how to live without crime, and such a practice of isolation is directly contrary to most theologies which emphasize the importance of active participation in a faith community in helping people live a good life. The pro-social benefits of this human interaction between volunteers and offenders in a prison setting ought not to be underestimated.

If inmates are to benefit from this human interaction and communal experience, it seems they must become involved at a certain level of intensity. Mere attendance at the odd worship service, Bible study, or Jumuah prayer simply is not enough to bring about change or development. As with other correctional programs, religion is not a panacea, A-.S• rather religion works for some people in some circumstances. One of these circumstances seems to be a certain level of attendance at the religious programs.

The findings suggest that correctional theory and practice ought to include active religious participation among those factors that are predictive of in-prison infractions such as age, criminal history and other risk factors like attachment to work and family. And because research is finding that the factors that are predictive of in-prison infractions also predict recidivism, the findings also suggest that religious participation may be an important variable in predicting recidivism. In short, the study supports the widely held view that religious involvement is positive as an influence on the rehabilitation of adult offenders.

As is usual, there are methodological limitations to this study, which means that we must interpret its findings carefully. The major threat to the validity of these findings arises from what is called self-selection bias or specification error and the fact that the subjects in our two groups—religious and non-religious attenders—were not randomly assigned, in the experimental fashion, to those two groups. This means that we may have failed to measure both groups on some crucial variable that relates to reduced levels of infractions, such as motivation to change, and so have a spurious effect with regard to religious participation and reduced levels of infractions.

Following Heckman, we believe that the lack of random assignment is not a critical methodological limitation. “Selection bias arises because of missing data on the common factors affecting participation and outcomes. The most convincing way to solve the selection problem is to collect better data. This option has never been discussed in the recent debates over the merits of experimental and econometric approaches and has only recently been exercised” (Heckman, 1979). Collecting better data is precisely what we did in this study. We were able to account for the religious participation level of a very large number of inmates-1,597 over a one-year period—in a setting or context that was the same for each of the subjects over that one-year period. Unlike previous studies, which either relied on self-reported religiosity or very incomplete measures of participation in religious programming, we tied our measure of religiosity to a concrete behavioral measure and gained a complete picture of the in-prison religious programming involved for each of the subjects in our study. In addition, we collected as much information as possible on the demographics and criminal history risk factors of our subjects to control for all the factors that might influence participation and outcomes.

One important variable that we were not able to collect information on was involvement in other programming during the study period. The lack of other program involvement data is a weakness in the design of our study. Such involvement could be related to participation in religious programs and to our outcome variable of infractions. Unfortu-

nately, this data was simply not available. However, this lack of information is not crucial in this study because, due to budget cutbacks, Lieber had very little programming available beyond basic work assignments. Given the foregoing limitations, our research design was methodologically sound. Our study was guided by a theory, collected thorough data, used a quasi-experimental design that included a longitudinal element so as to look at the issue of causality, and used multivariate statistical measures and controls. In summary, the research design strengthens the findings of the study.

The study looked at religion from a global perspective and did not make any distinction between different types of religious programming among different religious groups. We suspect the influence of different types of religious programming on rehabilitation is not uniform. Undoubtedly, based on such factors as training, style, content, frequency and quality of leaders or presenters, there will be different effects of various religious programs on the rehabilitation process of offenders. We leave the question of the differential impact of different kinds of religious programs to future studies. What is valuable about this study is that we were able to discern patterns of a global religious impact on reducing infractions. In this way, the study supports the widely held cultural belief in the U.S. that religion plays a role in the creation and maintenance of a law-abiding community, and argues that the religious variable is an important one that must be considered in the mix of variables and “best correctional practices” related to offender rehabilitation.

The theology of redemption essentially examines the process of turning evil into good or transforming a bad situation into a good situation. Rehabilitation is often thought of as the movement of a person from committing infractions or crime to not committing infractions or crime. But of course, such a purely functional definition of rehabilitation does not do justice to the profound change that can take place in a person’s life or situation as he or she turns from crime. Ultimately religion in a correctional setting seeks to influence offenders not only to desist from crime but also to grow in living well and justly. That such a transformation from selfishness to self-giving may be taking place among the religiously-involved men incarcerated at Lieber can be discerned in the findings of this study and the words of one of the subjects:

Before [being in prison], it was all me. Now I know life is also about relationships. I have to think of others and God. If you’re serious about God, you have to take on the nature of God, and God cares about other people too.

REFERENCES

Alexander, J., & Chapman, W. It (1981). Adjustments to prison: A review of innate characteristics associated with misconducts, victimization, and self-injury in confinement. (Classification Improvement Project, Working paper 10, 1986. Prison Crowding: Search for Functional Correlations): State of New York Department of Correctional Services.

Andrews, D. A. (1995). The psychology of criminal conduct and effective treatment. In J. McGuire (Ed.), What Works: Reducing Criminal Reoffending (pp. 35-62). New York: John Wiley.

Andrews, D. A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F. T. (1990). Does correctional treatment work? A clinically relevant and psychologically informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28, 369-404.

Baier, C. (2001). If you love me, teach my commandments: A meta-analysis of the effect of religion on crime. Research in Crime & Delinquency, 38 (1), 3-21.

Bailey, W. C. (1966). Correctional outcome: An evaluation of 100 reports. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, 57, 153-160.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Clear, T., & Myhre, M. (1995). A study of religion in prison. JARCA Journal on Community Corrections, 6 (6), 20-25.

Clear, T., Stout, B., Dammer, H., Kelly, L, Hardyman, P., & Shapiro, C. (1992). Prisoners, Prisons, and Religion: Final Report. Newark, NJ: School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University.

Colson, C. (1979). Life Sentence. Richmond, VA: Chosen Books.

Colson, C. 8c Van Ness, D. (1988). Convicted: New Hope of Ending America’s Crime Crisis. Westchester, IL: Crossway Books.

Ellis, L (1985). Religiosity and criminality: Evidence and explanations surrounding complex relationships. Sociological Perspectives, 28, 501-520.

Evans, T. D, Cullen, F. T., Dunaway, R. G., & Burton, V. S. (1995). Religion and crime reexamined: The impact of religion, secular controls, and social ecology on adult criminiology. Criminology, 21, 29-40.

Fowler, J. (1981). Stages of Faith: The Psychology of Human Development and the Quest for Meaning. San Francisco: Harper & Row.

Gartner, J., Larson, D. B., & Allen, G. D. (1991). Religious commitment and mental health: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19(1),6-25.

Gartner, J., O’Connor, T., Larson; D., Young, M., Wright, K., & Rosen, B. (1990). Rehabilitation, Recidivism and Religion: A Systematic Literature Review. Baltimore, MD: Loyola College in Maryland.

Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. EconOtnetrica, 47(1), 153-161.

Hoge, D. R. (1972). A validated intrinsic motivation scale. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 11, 369-376. v.:

Johnson, B. R. (1984). Hellfire and Corrections: A Quantitative Study of Florida 4t Prison Inmates. Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Florida State University.

Johnson, B. It, Larson, D. B., & Pitts, T. C. (1997). Religious programs, institutional adjustment, and recidivism among former inmates in prison fellowship programs. Justice Quarterly, 14(1), 501-521.

Knudten, R. D., & Knudten, M. S. (1971). Juvenile delinquency, crime, and religion. Review of Religious Research, 12, 130-152.

Law, M. A. (1993), Predicting Prison Misconduct. St. John, NB: University of New Brunswick.

Lonergan, B. (1972). Method in Theology. New York: Seabury Press.

McKelvey, B. (1977). American Prisons: A History of Good Intentions. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith.

Motiuk, L. (1983). Antecedents and Consequences of Prison Adjustment: A Systematic Assessment and Reassessment Approach. Ottawa: Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Carleton University.

O’Connor, T. (1995). The impact of religious programming on recidivism, the community and prisons. IARCA Journal on Community Corrections, 6(6), 13-19.

O’Connor, T., & Parikh, C. (1998). Best practices for ethics and religion in community corrections. ICCA Journal on Community Corrections, 8(4), 26-32.

O’Connor, T. P., Parikh, C., & Ryan, P. (1997). The South Carolina Initiative Against Crime Project: 1996 Volunteer Survey (Evaluation). Silver Spring, MD: Center for Social Research, Inc.

O’Connor, T., Ryan, P., Yang, F.; Wright, K., & Parikh, C. (1996, August). Religion and Prisons: Do Volunteer Religious Programs Reduce Recidivism? Paper presented at the American Sociological Association Convention, New York.

Pass, M. G. (1999). Religious orientation and self-reported role violations in a maximum security prison. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 28 (3/4), 19-134.

Petersilia, J. (1995). A crime control rationale for reinvesting in community corrections. The Prison Journal, 75(4), 479-496.

Prison, F. (1991). Beyond Crime and Punishment. Washington, DC: Prison Fellowship.

Sampson, R. J., & Laub, J. H. (1993). Crime in the Making: Pathways and Turning Points Through Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Skotnicki, A. (1992). Religion and the Development of the American Penal System. Berkeley, CA: Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation, Graduate Theological Union.

Sloane, D., & Potvin, R. (1986). Religion and delinquency: Cutting through the maze. Social Forces, 65, 87-105.

Sumter, M. T. (1999). Religiousness and Post-Release Community Adjustment. Tallahassee, FL: Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Florida State University.

Sumter, M. T., & Clear, T. (1998, March 14). An empirical assessment of literature examining the relationship between religiosity and deviance since 1985. Paper presented at the Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences Conference, Albuquerque.

Sundt, J., & Cullen, F. T. (1998). The role of the contemporary prison chaplain. Prison Journal, 78(3), 271-298.

Tittle, C. R., & Welch, M. (1983). Religiosity and deviance: Toward a contingency theory of constraining effects. Social Forces, 61(653-682).

U.S. Department of Justice (1993). Survey of State Prisoners, 1991. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Government Printing Office.

Wright, K. N. (1985). Developing the prison environment inventory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 22(3), 257-277.

AUTHORS’ NOTES

Tom O’Connor is the administrator of religious services for the Oregon Department of Corrections and the president of the Center for Social Research headquartered in Silver Spring, Maryland. Michael Perreyclear is a research associate, Center for Social Research. Active in prison ministry for a decade, he is currently studying pastoral ministry with the Independent Study Institute, Southern Baptist Convention, Nashville, Tennessee. Financial and other support for this research was provided by the Center for Social Research, the South Carolina Department of Corrections, Prison Fellowship Ministries, and the Oregon Department of Corrections. The authors would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following to the study: Director Michael Moore, Chaplains Terry Brooks, Robert Shaver, James Brown, and Richard Tamer and their clerks (Michael, Stacy, and Kamathaii), Dr. Lorraine Fowler, Ms. Meesirn Lee, Ms. Mei-chu Tang, Ms. Barbara Simon, and Ms. Deanne Williams, South Carolina Department of Corrections; Dr. Karen Strong, Mr. Fred Kensler, and Mr. Jimmy Stewart, Prison Fellowship Ministries; and Ms. Patricia Ryan and Dr. Crystal Parikh, Center for Social Research. Address correspondence to Thomas P. O’Connor, Administrator, Religious Services, Oregon Department of Corrections, 2575 Center Street NE, Salem, OR 97310 (E-mail: tom.p.oconnor@doc.state.or.us).