The Sociology of Humanist, Spiritual, and Religious Practice in Prison

The Sociology of Humanist, Spiritual, and Religious Practice in Prison:

Supporting Responsivity and Desistance from Crime

Tom P. O’Connor*1, and Jeff B. Duncan2

1 Transforming Corrections, 1420 Court St. NE. Salem, Oregon 97301, USA

2 Oregon Department of Corrections, 2575 Center St. NE., Salem, OR 97301, USA

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Received: 20 September 2011 / Accepted: 24 October 2011 / Published: 2 November 2011

(This article belongs to the Special Issue Current Studies in the Sociology of Religion)

Abstract:

This paper presents evidence for why Corrections should take the humanist, spiritual, and religious self-identities of people in prison seriously, and do all it can to foster and support those self-identities, or ways of establishing meaning in life. Humanist, spiritual, and religious (H/S/R) pathways to meaning can be an essential part of the evidence-based responsivity principle of effective correctional programming, and the desistance process for men and women involved in crime. This paper describes the sociology of the H/S/R involvement of 349 women and 3,009 men during the first year of their incarceration in the Oregon prison system. Ninety-five percent of the women and 71% of the men voluntarily attended at least one H/S/R event during their first year of prison. H/S/R events were mostly led by diverse religious and spiritual traditions, such as Native American, Protestant, Islamic, Wiccan, Jewish, Jehovah Witness, Latter-day Saints/Mormon, Seventh Day Adventist, Buddhist, and Catholic, but, increasingly, events are secular or humanist in context, such as education, yoga, life-skills development, non-violent communication, and transcendental meditation groups. The men and women in prison had much higher rates of H/S/R involvement than the general population in Oregon. Mirroring gender-specific patterns of H/S/R involvement found in the community, women in prison were much more likely to attend H/S/R events than men.

Keywords:

- prison

- humanist

- spiritual

- religious

- responsivity

- desistance

- gender

- religion

- corrections

- treatment

Introduction:

Prisons, by nature, are dangerous places. Prisons concentrate large numbers of people in crowded conditions with little privacy and few positive social outlets. Prisons hold healthy people dealing with issues of loss, fear, shame, guilt and innocence, alongside people with mental illnesses, varying levels of maturity, sociopathic tendencies, and histories of impulsivity and violence. The sense of danger and the generally oppressive nature of prisons make it all the more remarkable that prisons can also be places of reflection, exploration, discovery, change and growth. St. Paul, Henry David Thoreau, Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, Aung San Suu Kyi, and countless men and women have all used their time in prison for good.

Malcolm X dropped out of school after eighth grade and gradually got involved in prostitution, burglary, drugs, and firearms. In 1946, when he was 21, Malcolm was sentenced to 8 to 10 years in the Massachusetts state prison system for larceny and breaking and entering. During his first year in prison Malcolm was disruptive and spent quite a bit of time in solitary confinement. “I preferred the solitary that this behavior brought me. I would pace for hours like a caged leopard, viciously cursing aloud to myself.” ([1], p. 156) Then, a self-educated and well regarded prisoner called Bimbi – “he was the first man I had ever seen command total respect…with his words” – inspired Malcolm to take up education, study and learning ([1], p. 157). Malcolm became more and more interested in religion and was advised by a religious leader to atone for his crimes, humbly bow in prayer to God and promise to give up his destructive behavior. After a week of internal struggle, Malcolm overcame what he describes as a sense of shame, guilt and embarrassment, and submitted himself in prayer to God and became a member of the Nation of Islam. It was a turning point, the kind of ‘quantum change’ described by William Miller in Quantum Change: When Epiphanies and Sudden Insights Transform Ordinary Lives [2]. “I still marvel at how swiftly my previous life’s thinking pattern slid away from me, like snow off a roof. It is as though someone else I knew of had lived by hustling and crime.” “Months passed by without my even thinking about being imprisoned. In fact, up to then, I had never been so truly free in my life.” ([1], p. 173) This jail-house religious conversion experience set the direction for Malcolm X’s lifelong journey of self, religious, racial, political, class and cultural discovery, and his profound influence on American life, which continues to be a topic of immense importance and debate to this day [3].

There are many similar prison stories of conversion leading to successful desistance from crime and a generous life of giving to one’s culture, community, and country [4]. In their article “Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars: Prison Conversions and the Crisis of Self-Narrative”, Maruna, Wilson and Curran (2006) make two important points. Their first point is the lack of social science knowledge about religion and spirituality in this unique context of incarceration. “The jail cell conversion from “sinner” to true believer may be one of the best examples of a “second chance” in modern life, yet the process receives far more attention from the popular media than from social science research.” Their second point is that the discipline of “narrative psychology” can provide explanatory insight into the phenomenon of religious and spiritual conversion in prison. Prisoner conversions, they argue, are a narrative that “creates a new social identity to replace the label of prisoner or criminal, imbues the experience of imprisonment with purpose and meaning, empowers the largely powerless prisoner by turning him into an agent of God, provides the prisoner with a language and framework for forgiveness, and allows a sense of control over an unknown future.” [5]

Todd Clear and a group of colleagues, such as Harry Dammer and Melvina Sumpter, explored the meaning and impact of religious practice in prisons throughout the US in a series of ethnographic and empirical studies. They found this practice helped people to psychologically adjust to prison life in a healthy way [6,7], and to derive motivation, direction and meaning in life, hope for the future, peace of mind, and make a shift in their lifestyle or behaviors [8,9]. High levels of religious practice and belief in a transcendent being were also related to positive post-prison adjustment in the community upon release [10]. Interestingly, Clear et al. argue that the main role of religion and spirituality in prison is not to reduce recidivism but to prevent, or at least ameliorate, the process of dehumanization that prison contexts in the U.S. tend to foster. Religion and spirituality in prison help to humanize a dehumanizing situation by assisting prisoners in coping with being a social outcast in a context that is fraught with loss, deprivation, and survival challenges [11]. Along these lines, Cullen et al. argue that criminologists must be more willing to help discover and support ways in which correctional institutions can be administered more humanely and effectively [12]. The practice of religion and spirituality in prison is one way to foster humanity and support desistance in a social context that can be inherently inhumane.

The Washington State Institute for Public Policy (WSIPP) meta-analysis of the impact of rehabilitation programs on recidivism included six ‘faith-based’ or ‘faith-informed’ studies that met their standards for methodological quality or rigor, and concluded that the findings on the impact of faith-based interventions on recidivism were “inconclusive and in need of further research”. Interestingly, four of the six studies in the meta-analysis failed to find an overall program effect on reducing recidivism, but two found a positive effect, one of which was also the study with the highest effect size (−0.388) for reducing recidivism, among the 291 evaluations that met the rigorous methodological criteria for acceptance in the meta-analysis. The study with the highest effect size was a study of a faith-informed program for very high-risk sex offenders in Canada called Circles of Support and Accountability or CoSA [13]. Additional research conducted by CoSA since the meta-analysis confirmed the strong effect size findings for the CoSA program. [14] Johnson’s review of the broad literature on religion and delinquency/crime in the community and after prison is very helpful because it examines a wide range of outcomes for a wide range of religious variables, and includes a large number (272) of studies of varying methodological rigor. Johnson’s conclusion, however, that “clear and compelling empirical evidence exists that religiosity is linked to reductions in crime” is not fully supported by the WSIPP meta-analytic findings about the impact of faith-based programs/religion on reducing crime for ex-prisoners [15, p. 172]. O’Connor et al. discuss the six studies included in the WSIPP meta-analysis along with some additional studies, and expand on the generally encouraging but inconclusive state of the research findings on recidivism from the corrections literature [16]. Dodson et al. also review some of the literature in this area of recidivism but do not include all of the relevant studies in their review [17].

Important new findings from a series of eight meta-analytic studies commissioned by the American Psychological Association (APA) are very relevant to this question of the connection between religion and corrections. These eight studies looked at whether or not it ‘works’ to adapt or match psychotherapy to eight individual client characteristics. In correctional terms, this APA research relates to the third of the three main principles of the Risk-Need-Responsivity Model of rehabilitation, namely the principle of responsivity [18]. The evidence-based principle of responsivity in corrections has two aspects to it. First, ‘general responsivity’ states that correctional interventions should use cognitive-behavioral modes of intervention as offenders respond best to this style of programming. Second, ‘specific responsivity’ states that interventions need to be tailored to the specific ways in which individual clients respond to treatment; a very shy person will not do well in groups, an illiterate person will not do well in programs that require a lot of writing etc. Responsivity is about adapting treatment to the particular ways in which the offender population in general, and individual offenders in particular, respond to treatment. The APA studies concluded that it was “demonstrably effective in adapting psychotherapy” to four of the eight factors studied: (1) reactance/resistance; (2) client preferences; (3) culture; and (4) religion and spirituality (R/S). The APA now counsels all of its members to incorporate a person’s religion and/or spirituality into their treatment (regardless of the therapist’s religion and/or spirituality), because doing so produces better treatment outcomes. “Patients in R/S psychotherapies showed greater improvement than those in the alternate secular psychotherapies both on psychological (d = 0.26) and spiritual (d = 0.41) outcomes.” [19].

The APA meta-analytic study on the outcomes of adapting psychotherapy to a patient’s particular religious and spiritual outlook categorized these R/S outlooks into four different types of spirituality based on the type of object a person feels a sense of closeness or connection to: (1) humanistic spirituality; (2) nature spirituality; (3) cosmic spirituality; and (4) religious spirituality [20]. Many humanists, secularists and atheists etc., however, do not like to use word “spiritual” to describe their perspective on life, so we prefer to collapse this fourfold categorization into a threefold classification based on a person’s way of making ultimate meaning in the world and their affective connection to the world and the transcendent: (1) humanist; (2) spiritual (includes both nature and cosmic spirituality); and (3) religious. Humanists tend to find meaning in human life itself and do not relate to a transcendent being or spirituality beyond human life. Sometimes referred to as secularists or ‘Nones’ (no stated religious preference, atheists, agnostics), this group of people is growing and now accounts for 15% of the US public [21]. On the other hand, people who are spiritual and/or religious, (many people say they are both spiritual and religious) [22], find meaning in life precisely by relating to some being or force that transcends human life. However one categorizes the different types, it is important for Corrections to take note that the APA has recommended that all psychologists and counselors should integrate humanism, spirituality, and religion into their work in a way that matches each client’s particular way of establishing ultimate meaning in life or feeling connected to something that is vitally important in their lives [19,20].

A new federal law, passed in 2000, called the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA), has dramatically reduced the ability of prisons and jails to restrict humanist, spiritual or religious (H/S/R) accommodations because of security or practical concerns. Just as prisons and jails must provide inmates with access to health care, they must now provide inmates with the ability to express and practice their belief and meaning systems, unless there is a compelling government reason not to do so. The Supreme Court has consistently ruled that people do not lose their First Amendment constitutional rights to practice their religion, spirituality, or way of life, when they are incarcerated. Before RLUIPA, prisons had fairly wide scope as to what they would and would not accommodate. RLUIPA and a series of other US cultural and legal developments, have meant that the “topic of religion and the criminal justice system is now clearly on the national criminological agenda” [23]. These First Amendment rights and responsibilities extend beyond spirituality and religion into humanism. In 2005, the US Court of Appeal did not declare that atheism was a religion, but did decide that atheism was afforded the same protection as religion under the First Amendment, and ordered a prison in Wisconsin to allow an inmate to form a study group for atheists alongside the religious study groups they already allowed [24].

In his acclaimed book, A Secular Age, Charles Taylor describes what it means to live in a modern secular democracy and a secular age. For Taylor, every person can now choose how they will create a sense of ultimate meaning for their life, and relate to the big questions of health, justice, suffering, evil, death and the purpose of life. The more traditional choice derives meaning from a diverse range of religious and spiritual traditions, which posit a transcendent source or ground of meaning, usually called God or the Divine. Now that we live in a secular age, people can and do choose to make meaning in a way that makes no reference to a transcendent God/Divinity, but only to human life and the human condition. This purely secular or humanistic way of making meaning is new; historically, this choice has never been available on a broad societal level. Nowadays, people take this choice for granted [25]. Prison chaplains have a unique potential, by way of their training, prison roles, skills and interests, to work with all three ways of making meaning – humanist, spiritual and religious [16]. Working effectively with all three paths, however, is a challenge for some prison chaplains and prison chaplaincies. The legislative hearings for the RLUIPA act (above) in the US make it clear that RLUIPA was enacted, in large part, because various prison systems and chaplains were not equally or fairly accommodating the wide variety of humanist, spiritual and religious traditions and meaning-making represented in their prisons. Similarly, Beckford and Gilliat, devote a whole book to making the point that structural and sociological issues make it difficult for English and Welsh prison chaplains to provide “equal rights in a multi-faith society”. The English and Welsh prison chaplains function in a social system that gives a privileged position to the Church of England, often referred to as the “national church”. This meant that, until recently, a very large majority of the prison chaplains were from the Church of England/Anglican tradition. The dominant position of the Church of England chaplains increasingly caused problems of equal access and opportunity for a variety of non-Christian faiths as English and Welsh society became more multi-faith [26]. “The reason for highlighting the structural setting of religion in prison rather than the beliefs and actions of individuals was to expose the social, organizational and cultural factors which shape the opportunities for prisoners to receive religious and pastoral care.”

To summarize many people, like Malcolm X, undergo profound conversion experiences in prison that brings about a quantum change in the trajectory of their life; the practice of H/S/R in prisons and jails is constitutionally protected; and this practice has been found to help people adjust, psychologically and behaviorally, to prison life and develop personal narratives and identities that support desistance from crime. Further research will determine whether or not, and how, this practice is related to reductions in recidivism. Evidence from the field of psychology on the evidence-based responsivity principle of effective correctional programming, strongly suggests that treatment and correctional staffs in prisons, jails, probation and parole should incorporate a person’s H/S/R into their correctional treatment and supervision practices. It is increasingly important, therefore, to have an accurate understanding of how H/S/R functions in a correctional setting and how to foster H/S/R in these unique contexts.

Understanding Humanism, Spirituality, and Religion in a Prison Setting

There are a few excellent ethnographic studies that seek to understand the meaning and role of H/S/R in the lives of prisoners [7,8, 27], but to our knowledge, there is not a single systematic or comprehensive description of H/S/R practice in prison. Maruna argues that researchers and practitioners who study correctional interventions often ask the question “What works?” but fail to ask the equally important question “How does it work?” [28]. O’Connor et al. review the literature on H/S/R in prisons and community corrections, and much of this literature is focused on the question of whether it works, rather than how it works [16,29,30,]. Most of the literature is also focused on organized religion but, as we have argued above, this conceptual approach needs to make a shift to include all three ways of making ultimate meaning: humanism, spirituality and religion. In this paper, we describe the sociology of H/S/R in a correctional system, specifically the Oregon state prison system, and leave the question of H/S/R content and outcomes to future papers [31]. An important first step to answering the “how does it work” question is to describe and understand the phenomenon we are questioning. To put it simply: What does H/S/R look like in a prison context?

The Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC) has a computerized scheduling system that helps organize and track the work and program involvement (education, cognitive, drug and alcohol treatment etc.) of the approximately 14,000 men and women who are incarcerated in 14 prisons around the state. Beginning in 2000, the department’s Religious Services Unit began to add all of the events and services it organized to the scheduling system in each of the prisons. Gradually, the accuracy and completeness of the H/S/R data entry improved in each prison, and by 2004 the data was of sufficient quality to initiate the present study.

The Oregon Department of Corrections organizes what it calls the Religious Services unit in a different way than many other state prison chaplaincy systems. Chaplains in many U.S. state prison systems are hired by the prison where they will work, and are supervised by a deputy warden/superintendent or the head of prison programming. In Oregon, the Religious Services unit is part of a centralized Transitional Services Division that has responsibility for overseeing the intake assessment/classification center, and the education, drug and alcohol, H/S/R, and reentry services for all of the prisons. So the Religious Services unit has its own centrally-based senior manager or Administrator who sets the direction for the statewide H/S/R services at each of the prisons, and oversees the budget, goals/policies, and hiring, training and supervision of the chaplains and other staff in the Religious Services Unit. Tom O’Connor, one of the authors on this paper, held the Administrator of Religious Services position with the Oregon Department of Corrections from 2000 to 2008. Currently, there are 22 full-time chaplains, two half-time chaplains, and seven other staff members in the Religious Services unit [32]. The staff members in the unit serve the H/S/R needs of all inmates, and they come from several different faith backgrounds including: Zen Buddhist, Sunni Muslim, Presbyterian, Unitarian, Baptist, Foursquare Christianity, Lutheran, Shambhala Buddhist, Latter-day Saints, Methodist, Missouri Synod Lutheran, Greek Orthodox etc. When we collected the data for this study (2004 to 2005), the Religious Services staff makeup was basically similar to the current makeup, though slightly smaller and less religiously diverse.

The chaplains and other staff in the Religious Services unit are responsible for four kinds of programs or services: (1) the H/S/R services and programs in the 14 prisons; (2) a statewide faith and community-based reentry program called Home for Good in Oregon[33]; (3) a statewide volunteer program for about 2000 volunteers; and (4) a victim services program that includes the Victim Information and Notification Everyday (VINE) program and a facilitated dialogue program between victims of serious crime and their incarcerated offenders [32]. Almost all of the services and events organized by the ODOC chaplains are religious or spiritual in nature, however, the chaplains are increasingly involved in facilitating services that take place in a humanist or secular context, without any religious or spiritual overtones, such as non-violent communication classes, social study groups, victim-offender dialogues, restorative justice programs, third level educational programs such as Inside-Out, and non-religious meditation programs such as Transcendental Meditation [34]. The chaplains also do a great deal of direct counseling, informal interacting, and death/grief work with inmates who do not have any religious or spiritual background or practice.

The Oregon prison chaplains would not be able to meet the diverse and widespread H/S/R needs of the men and women in prison without the help of a substantial cadre of volunteers. These volunteers are an indispensible part of the sociology we are examining, and many voices such as the Director of the National Institute of Corrections are now arguing for an expanded role for volunteers in corrections [35]. In this paper, we give a brief overview of these volunteers; a forthcoming paper will examine the volunteer program in depth [36]. The largest group of volunteers is related in some way to religious faith traditions or spiritualties. Approximately 75% of the almost 2,000 men and women who currently volunteer for prison and/or reentry programs with the Oregon Department of Corrections, are religious or spiritual volunteers who come from a wide variety of faith and spiritual traditions such as Native American, Jewish, Protestant, Catholic, Hindu, Buddhist, Seventh Day Adventist, Latter Day Saints, Jehovah Witness, and Earth-Based or pagan such as Wicca. Ten percent of the prison volunteers work in the area of drug and alcohol recovery, primarily from the Alcoholics and Narcotics Anonymous (AA and NA) traditions, and tend to fall into the “spiritual” category, along with some Native Americans, Wiccans, and Buddhists etc., who prefer to think of themselves as spiritual but not necessarily religious. The AA and NA volunteers do not usually self-identify as ‘religious’ in the sense of belonging to an organized religion, but often consider themselves as spiritual because a “higher power” is a core part of their way of being and making meaning. McConnell recently did a series of ethnographic interviews with a diverse group of spiritually and religiously involved men in two of Oregon’s prisons (a maximum security prison with a population of about 2,400, and a medium security prison with a population of about 800). Tony, one of the men interviewed by McConnell, who had a Native American ethnic heritage but no previous exposure to Native American spiritual practices prior to being in prison, expresses this identification with spirituality and not religion:

The first sweat [sweat lodge ceremony] I went to, I still had a lot of the anger, and I went in, and I heard some of the stories that they told…. A lot of their history, combined with their – I wouldn’t call it a “religion” – but their beliefs. And then, a lot of their personal things that they were kinda lettin’ go of and what not. And I was able to just let go of a lot of my anger. And was reassured that things, you know, if you have a good heart, a good mind and what not, it doesn’t matter if it’s God or Great Spirit, but you will be rewarded in time. ([27], p. 255)

The final 15% of volunteers in Oregon tend to work out of a wide variety of humanist or secular contexts and help with high school and college education, cultural clubs, re-entry, communication skills, meditation, recreational activities, life-skills development and administrative tasks in the department. Some of these ‘humanist’ volunteers work out of the Religious Services unit, and some of them work out of other units such as Education and Activities. A good example of this humanist or secular group would be many of the volunteers in the Inside-Out Prison Exchange program. Trained Inside-Out professors teach accredited college courses inside a prison, but half of the students in the class are inmates and half are outside students from a local university. Inside-Out has held nearly 200 classes with over 6,000 students, and trained more than 200 instructors from over 100 colleges and universities in 35 US states and Canada. The Inside-Out Program ‘increases opportunities for men and women, inside and outside of prison, to have transformative learning experiences that emphasize collaboration and dialogue, inviting participants to take leadership in addressing crime, justice, and other issues of social concern.’[37]

These humanist, spiritual and religious volunteers are a huge resource for corrections and public safety; they are dedicated to making a difference in society and helping to lift people out of crime and into productive lives in the community.

The Sociology of Humanist, Spiritual and Religious Practice in a Prison Context

We turn now to describe the H/S/R background and involvement of people who spend at least one year in prison. The Oregon correctional system sends people to the state prison system when their sentence length is one year or longer. Those who are sentenced to less than a year serve their time in the county jail system. Not everyone who is sentenced to the state prison system, however, spends a full year in prison because their time in the County jail awaiting trial etc. is counted toward their sentence. The population for this longitudinal study was the 3,009 men (90%) and 349 women (10%) who entered the Oregon state prison system at any point during 2004 and who were still in the system one year later from their original 2004 date of intake into the system. We started collecting data on the H/S/R involvement of these men and women from their particular date of entry in 2004 and followed them all for a one-year period from that date.

Table 1 shows the basic demographics for both the men and the women. Compared to men, the women were more likely to be White, and Native American and less likely to be Asian, African American and Hispanic. Men were much more likely to be a gang member and to have committed a sexual offence than women. The average age of the men and women, however, was the same. So, demographically, the men in our study differ significantly to the women.

Demographics of Study Population (N = 3009 males and 349 females).

Oregon has one central intake or receiving center for men and women who enter prison. The intake center is located on the grounds of the only women’s prison in Oregon. The women and men are held in separate parts of the intake center for about three weeks and then moved to the only women’s prison in Oregon or one of 13 male prisons for the remainder of their sentence. The men might be moved several times between these 13 prisons prior to their release. The women can only move between the medium and minimum sections of the women’s prison which are located in separate buildings on the same grounds as the intake center. During intake, the ODOC conducts a battery of criminogenic risk, need, and responsivity assessments, including security, education, drug and alcohol, health, dental and psychological assessments.

The department does not keep any data on the H/S/R self-identity or affiliation of the men and women in the state prison system, and generally permits anyone to attend whatever H/S/R service or activity might be of interest to them, regardless of their self-identity. In 2004, the Religious Services staff made a voluntary H/S/R self-report assessment available to each person coming through intake, and 684 out of the 3009 men (23%) and 124 of the 349 women (36%) took the H/S/R assessment.

The first question in the survey was “Choose one statement that describes you the best.” with four possible answers: (1) I am spiritual and religious; (2) I am spiritual but not religious; (3) I am religious but not spiritual; and (4) I am neither spiritual nor religious. The men and the women answered this question in a very similar fashion: 60% of the men and 66% of the women said they were ‘spiritual and religious’; 23% of the men and the women said they were ‘spiritual but not religious’; 9% of the men and 7% of the women said they were ‘religious but not spiritual’; and 8% of the men and 4% of the women said they were ‘neither spiritual nor religious’. So, most inmates consider themselves to be ‘both spiritual and religious.’ Almost a quarter, however, consider themselves to be ‘spiritual but not religious’, and relatively small percentages consider themselves to be either ‘religious but not spiritual’, or ‘neither spiritual nor religious’. This is roughly the same pattern that has been found in the general community, although people entering prison in Oregon may be different than the general population of Oregon in how they answer this question. One study with a general community sample from another state found that 74% were ‘spiritual and religious’, 19% were ‘spiritual but not religious’, 4% were ‘religious but not spiritual’, and 3% were ‘neither religious nor spiritual’ [22]. The neither ‘spiritual nor religious’ group probably equates in some way to a humanist group that tends to find meaning within the boundaries of human life (and not in relationship to a transcendent realm or object). Obviously, more research needs to be done before we can make clear distinctions between these H/S/R categories, but these figures give us a good starting point.

Humanist, Spiritual and Religious Affiliation at Prison Intake (N = 998).

Figure 1 shows the self-reported H/S/R affiliation for the 648 men and 124 women who voluntarily took the H/S/R assessment in 2004. Respondents could check multiple answers, and because 180 (23%) of the men and women did so, we tallied all of the responses for a total N of 998. So if a person listed one preference we counted that as one, and if a person listed 2, 3, or 4 preferences, we counted that as 2, 3, or 4 etc. Although these numbers are not representative of the entire intake population, they are the best estimate we have of the incoming H/S/R affiliation of the study population. Later in the paper we will see that the decision to voluntarily take the H/S/R assessment at intake was a predictor of who would attend H/S/R events in prison, so our sample is biased toward people who are more actively engaged in H/S/R. The majority (48%) say they are Christian/Protestant, followed by 7% Catholic, 7% Native American, 7% Don’t Know, 7% No Preference, 4% Other, 3% Latter Day Saint, 3% Earth Based, 3% Christian Scientist, 2% Jehovah Witness, 2% Seventh Day Adventist, 2% Buddhist and the remainder (6%) made up of very small numbers of Islamic, Agnostic, Jewish, Atheist, Hindu, Scientology, New Age, Confucian, Eastern Orthodox, and Hare Krishna (ISKON). Women were significantly more likely than men to say they were Christian/Protestant or Jewish, but equally likely to choose the other affiliations or self-identities. The unaffiliated 14% who said “no preference” or “don’t know” are a fairly large group, and some of these may tend toward the humanist perspective. While 14% of our samples choose ‘no preference’ or ‘don’t know’, only 4% said they were ‘neither spiritual nor religious’, so these terms are not synonymous. A 2008 study found that Oregon’s largest religious group was Evangelical Protestant (30%) or Mainline Protestant (16%), followed by Catholic (14%), and Latter Day Saints (5%). This study also confirmed what other surveys have found, that Oregon has one of the highest percentages of religiously unaffiliated adults in the country: 27% unaffiliated in Oregon compared to 16% nationally [38]. On the face of it, therefore, the H/S/R self-identities of people entering prison in Oregon seem to differ from the general Oregon population in some respects (fewer unaffiliated and fewer Catholic), and not to differ in others (similar percentages of Protestant and Latter-day Saints).

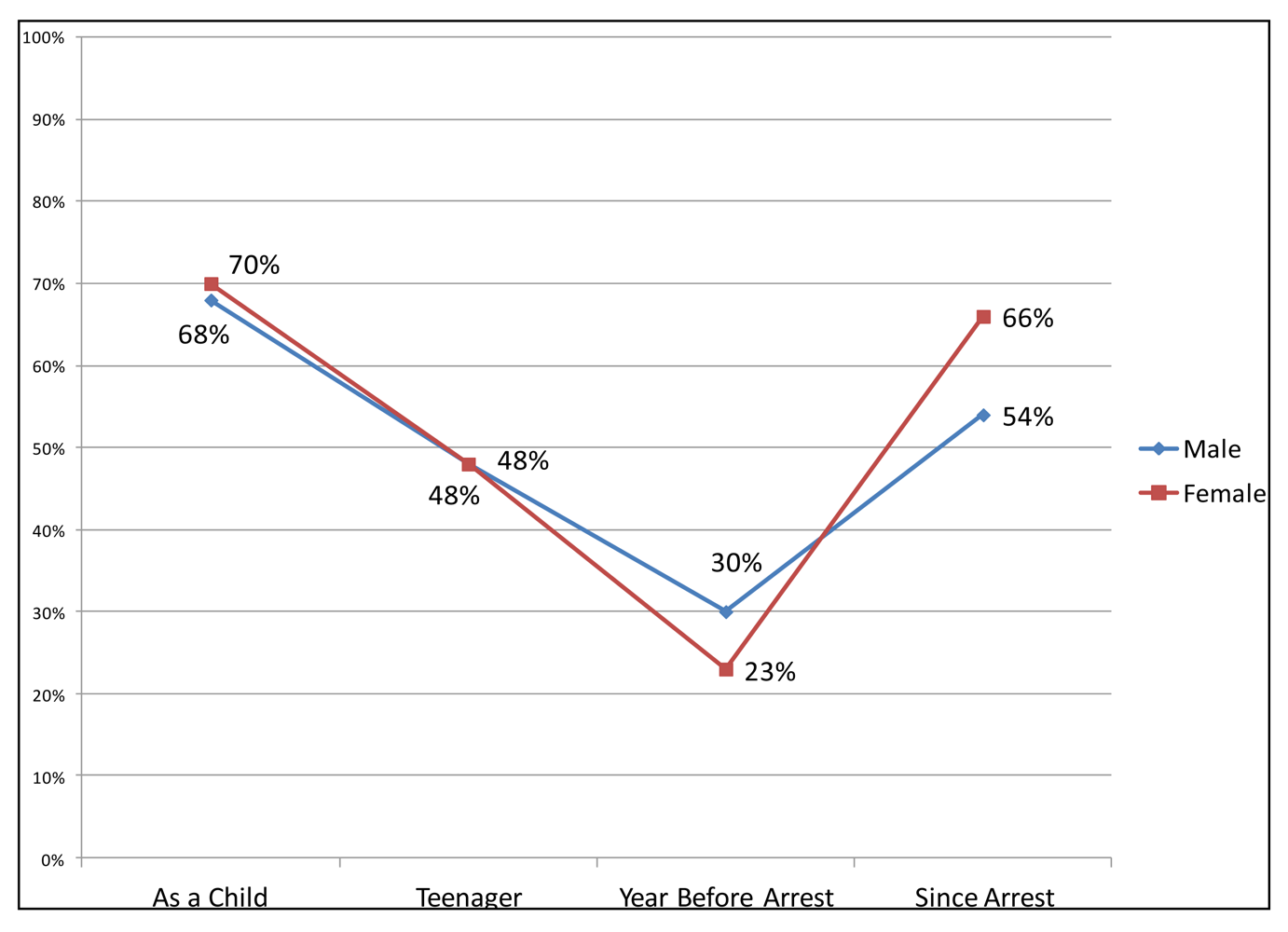

Religious/Spiritual Involvement (once a month or more) over Time for Females and Males (N = 772).

The H/S/R assessment at intake asked people how often they had attended a church, synagogue, mosque, sweat lodge etc.as a child, as a teenager, in the year prior to their arrest and in the year following their arrest. Figure 2 shows how the women and men responded to this question. We see a similar pattern for both men and women of high levels of attendance as a youth, with progressively falling levels of attendance up to the point of arrest, and then a dramatic increase in attendance following arrest. The pattern, however, is even more pronounced for the women than the men. The women (70%) and the men (68%) were equally likely to have attended some religious or spiritual group as a child, and as a teenager (48% for both). The women (23%), however, were less likely than the men (30%) to have attended in the year prior to their arrest, and more likely (66%) than the men (54%) to attend in the year after their arrest. Findings like these, together with the higher rate of women voluntarily taking the H/S/R assessment at the intake center, soon led us to conclude that we needed to consider men and women separately in every analysis as there are significant gender differences in H/S/R behaviors in prison. In many cases these gender differences of involvement mirror similar gender differences of H/S/R involvement in the general community.

Research has shown that, in the general population in America, there is a similar drop in religious/spiritual attendance for most people from their childhood to their teen years. During their early adult years, however, as factors such as having children begin to come into play, their attendance level returns to a level that is higher than in their teen years but not quite as high as in their childhood years [39,40]. In other words, the normal pattern of religious attendance in the general population is similar to a U curve. For the offender population, however, the pattern seems to have more of an extended downward slope on the U, followed by a later upturn upon being arrested and entering jail or prison. Most likely, this delayed response is triggered by the fact that people, once arrested, tend to be in institutions or situations with more time on their hands, more control and structure in their lives, their basic needs met, and less interpersonal conflict and substance abuse opportunities in their day-to-day lives. In this new context questions of meaning emerge in a new way. The following quotes from two Oregon inmates, first from Elijah, a Muslim, and second from Wayne, a Christian, nicely capture the influence of living in a structured environment on the exploration of personal meaning and introspection:

One of the things, when I was on the street before I came to prison, is that there was so much, so much goin’ on in my life, between school, my wife; we had a child. I didn’t really have time to really look inward. And I don’t know if I want to say “I didn’t have time.” I didn’t take the time. And, I’ve been able to do that now a lot more. One of the things about prison is that you have time to look inward ([27], p. 243).

I hadn’t slowed down enough to do any readin’ of the Bible or anything… You got a lot more time to just do nothing really. You either do something with your time when you’re here or you don’t… It [the Bible] is the only real thing that’s here, as far as I’m concerned… My heart’s not into goin’ out and hurtin’ people. My heart’s not into goin’ out and bullshitin’ and tellin’ lies, and just playin’, tryin’ to beef up myself to look better and good, and all this stuff ([27], p.248).

From the foregoing self-report information, we knew that a sample of men and women at the point of intake into the Oregon prison system were reporting much increased levels of engagement in religious and spiritual practices after arrest. Now the task was to explore, in a longitudinal manner, the actual patterns of H/S/R engagement from the point of intake forward into the first year of prison. First, we tracked each person in the 2004 intake population to discover the first and subsequent months they chose to attend any H/S/R event during their first 12 months of incarceration. For most of the first month of their incarceration, our subjects were at the intake center, and there are no H/S/R events or services at the intake center for the men. The women, however, are allowed to attend H/S/R events at the women’s prison because it is directly accessible from the intake center. To our surprise, we found that 80% of the women attended an H/S/R event during their first month of incarceration. The equivalent for the men was 32% (counting the first two months for the men). Just as we found a different pattern of self-reported religious involvement for the men and women in the year prior to and after their arrest, we found a different pattern of actual involvement for the men and women during their first year of incarceration.

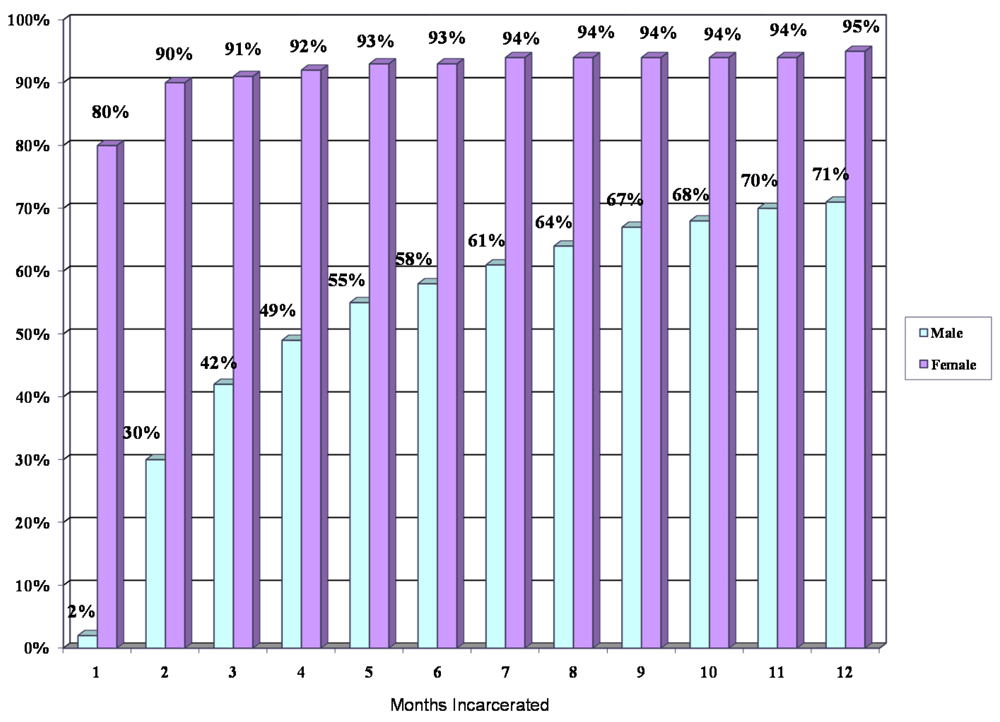

Cumulative Attendance for Male (N = 3009) and Female (N = 349) Across Months of Incarceration.

Figure 3 below shows the cumulative attendance rates over the first year for the men and the women. It is remarkable that by the third month, 91% of the women had attended at least one H/S/R service, and by the end of the year 95% of the women had attended. We do not know what the precise attendance level for these women was while they were in the community, but this level of attendance is probably higher than it would have been in the community. For the men, 49% had attended at least one H/S/R event by the third month, and 71% had attended by the end of the year; also a very high rate of attendance. The higher attendance rate among women mirrors a higher H/S/R attendance level and interest among women in the general US population [41]. In more than 49 countries around the world, studies have found a pattern of significantly higher interest in religion and spirituality among women compared to men [421]. Therefore, the higher pattern of involvement for women seems to be a consequence of gender and not of the prison context itself. The overall high levels of re-engagement for both the men and the women, however, seem to be a consequence of the prior arrest and prison context.

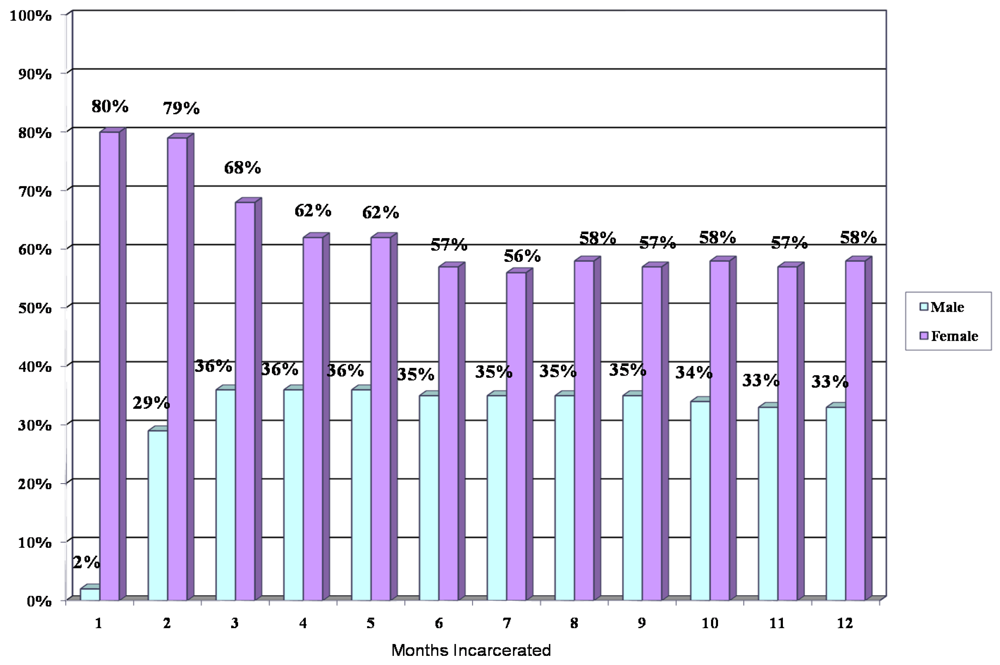

Average Attendance for Male (N = 3009) and Female (N = 349) Across Months of Incarceration.

The fact that 95% of the women and 71% of the men, a very large percentage of the population, had attended at least one H/S/R event during their first year in prison raises the question of how often these men and women attended overall. We examined this question of “dosage” or level of attendance in two different ways. First, we checked to see the average percent of attendance each month for both the men and the women as a group. Figure 4 shows the average attendance rates by male and female for each of the 12 months of our study. For the women, the first two months have the highest average attendance rates, at 80% and 79%. In the third month this drops to 68%, and then gradually settles to about 58% of the women attending each month. For the men, once again, the pattern is different. Very few of the men could attend during the first month, so the average attendance is almost 0%. For the second month, the average attendance is 29%, and by the third month it settles into an average monthly attendance rate of about 33% of the population. This means that the prison chaplains in Oregon, with the help of their volunteers, are directly engaging a large proportion of the total male and female population every month. This finding, therefore, confirms an earlier finding across state prisons that religious programming is the single most common form of programming in state prisons [43].

Percent of Men and Women Attending Religious or Spiritual Groups.

We found some very interesting religious and gender differences when we examined the kind of religious or spiritual service that people were attending. Protestant services (basically meaning any non-Catholic religious services) were at the top with 60.7% of men and 92.8% of women attending at least one Protestant service. Next was Seventh Day Adventist with 14.5% of the men and 28.9% of the women attending at least one service. The next highest was Catholic with 11.2% of the men and 18.3% of the women attending at least once, followed by a Native American with 6.6% of the men and 23.2% of the women. The pattern is clear (see Table 2): women are much more likely than men to cross-attend numerous types of religious and spiritual services. Also of note is the order of the religious or spiritual groups by size of participation – Protestant, Seventh Day Adventist, Catholic, Native American, Jehovah Witness, Latter Day Saints, Buddhist, Muslim and Earth-based/New Age for the men, and Protestant, Seventh Day Adventist, Latter Day Saints, Native American, Buddhist, Catholic, Jehovah Witness, and Muslim for the women. Clearly, therefore, the Protestant/Christian group, which represents a vast variety of different Christian groups, is by far the dominant group in terms of attendance for both men and women.

Levels of Attendance During The First Year of Incarceration by Male (N = 3009) and Female (N = 349).

Next, we examined how often people were going to events. Figure 5 reveals, as expected, a different pattern of attendance by gender. A very large group of men (45%) never attend or only attend once or twice in their first year, compared to only 8% of the women. Compared to the men, women were 7 times more likely to have attended an H/S/R event at least once. The same percentage of men and women (21%) attend from 3 to 12 times a year (up to once a month), and thereafter the women engage at much higher rates. It is important to note that a sizable percentage of both the men (24%) and the women (49%) attend at levels that approach weekly or more than weekly attendance. There is no easy way of comparing these levels of weekly or more attendance for inmates to the attendance levels for the general population in Oregon. In 2007, however, 32% of Oregonians said they attended religious services at least weekly, and the combined national US average was 39% with 44% of women and 34% of men self-reporting at least weekly attendance [38]. So it seems that women in Oregon prisons may be attending at slightly higher levels than women in Oregon communities, and men in Oregon prisons are attending at slightly lower levels than men in the community.

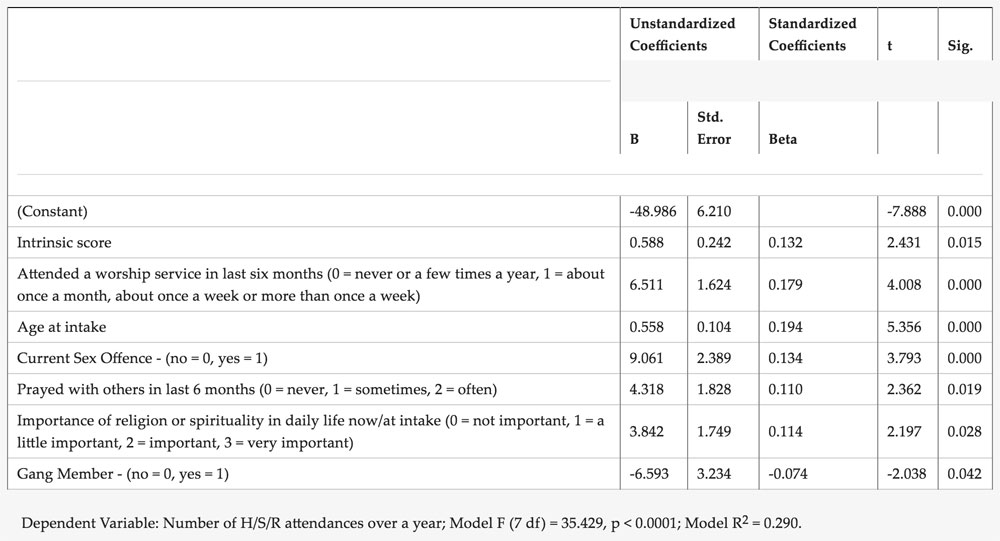

Linear Regression Model Predicting Number of Attendances.

Table 3 shows the results of a linear regression analysis on total number of H/S/R attendances of any type by men. Six factors were included in the model: having a current sexual offense, age at intake, voluntarily taking a spiritual assessment at intake, risk of recidivism, non-Hispanic versus Hispanic identification, and gang membership. These six factors, in that order, were significant predictors of which men attended H/R/S events more often (R2 = 0.111). The risk of recidivism score, which has been validated on Oregon inmates, ranges from 0 to 1. This score is automatically generated by the Department of Corrections at intake using a mathematical formula based on a person’s score on the following seven risk factors: age, earned time, sentence length, prior revocation, number of prior incarcerations, prior theft convictions, and type of crime (person, property or statutory). Men who had committed a sex offense, who were older, who had voluntarily taken a spiritual assessment at the intake center, or who were Hispanic were significantly more likely to attend H/R/S events more often. On the other hand, men with a higher risk of recidivism and who were members of a gang were significantly less likely to attend more often. None of these six factors were predictors of how often the women attended H/S/R events, and we were unable to generate a meaningful model for the women using the variables available to us, perhaps because so many of the women are attending at high levels.

Linear Regression Model Predicting Number of Attendances for Men Who Took an H/S/R Assessment at Intake.

It helps to interpret the linear regression results from Table 3 if we remember the finding from Table 2 above, namely that the Protestant/Christian group is by far the dominant group in terms of attendance for both men and women. So, the linear regression findings are heavily influenced by the people who are attending Protestant/Christian services. If we specified a linear regression model on people attending just Protestant/Christian or just Seventh Day Adventist services (the top two groups for men) the model is basically the same except that Non-Hispanic/Hispanic drops out in favor of Non-White/White. So, Whites are more likely to attend Protestant/Christian are Seventh Day Adventist services more often, along with those who had a current sexual offense, are older, voluntarily take a H/S/R assessment at intake, have lower risks of recidivism, or are not a gang member. Hispanics, however, are more likely to attend Catholic services along with people who have a current sexual offense, and are not a member of a gang, but the risk of recidivism, the age and the H/S/R assessment variables drop out of the model. For Native American attendance, the picture looks very different; people who are Native American, who have higher risks of recidivism (not lower, as in the other religious groups) and who are not a member of a gang are more likely to attend more often (R2 = 0.148), and the current sex offense, age and taking a H/S/R assessment at intake drop out of the model. Race and culture, therefore, have a big influence on who attends which religious or spiritual group, but in different ways for different groups. Similarly, having a current sexual offense, age, and risk of recidivism are important variables for attendance at most, but not all groups.The final analysis we did on our data set was to look at what the H/S/R assessment information might tell us about the subset of 684 men and 124 women who voluntarily took the assessment at the intake center. We have already shown that the mere fact of taking this assessment predicts who will attend religious and spiritual services more often. A linear regression analysis number of attendances using this subset of men and women produced some startling results. Table 4 below shows the factors that came into a model to predict number of attendances for this 648 male subset of our population. The first variable into the model is called “Intrinsic Score”. This variable comes from a 20 question intrinsic/extrinsic religiosity/spirituality scale [44] that was embedded in the H/S/R assessment. The scale asks questions to determine if a person uses their religion or spirituality in a more internal/intrinsic manner to make meaning, or a more external/extrinsic manner to create a social life. For example, one extrinsic oriented question in the scale asks people to respond (I strongly disagree, I tend to disagree, I’m not sure, I tend to agree, I strongly agree) to the following statement “I go to church (synagogue, mosque, sweat lodge etc.) because it helps me to make friends. A more intrinsic oriented question asks people to respond in the same way to the statement “It is important to me to spend time in private thought and prayer”. The scale produces an “intrinsic” score and an “extrinsic” score. The fact that the intrinsic score is the first variable into the model indicates that men who are going more often are going for internal reasons of making meaning. In an earlier regression model which was significant but not as strong as the model we ended up with, the extrinsic score also came into the model with higher scores negatively predicting who would attend more often (R2 = 0.262). The intrinsic and the extrinsic scores are not significantly correlated with each other for the men (they are weakly correlated for the women). The fact that both the intrinsic and extrinsic scores operate in this way shows that, contrary to often voiced sentiment, the men in the Oregon prison system who took a H/S/R assessment are attending services for largely internal, meaning driven reasons, and are not doing so to “get out of their cell”, “get some cookies and refreshments”, “to meet women volunteers” or “to hang out with and meet other inmates”.

Interestingly, age at intake, having a current sexual offense and gang member still come into the model for this subset of men, but the risk of recidivism and the race variables drop out from the model. Furthermore, three other variables from the H/S/R assessment come into the model along with intrinsic score – attendance at a worship service in last six months, prayed with others in the last six months, and how important is religious or spirituality in your daily life now. The F (7 df) = 35.429 value for the model is very high and very significant (<0.0001) and the R2 for the model is also very high at 0.290 (recall that R2 for the model in Table 3 with the full population was much lower at 0.111). So this H/S/R assessment tells us a great deal about the people who take an H/S/R assessment, and their answers highly correlate with their future religious and spiritual behaviors in a meaningful way.

Table 5 gives the equivalent linear regression findings for the women who completed an H/S/R assessment. You will recall that we were unable to find a meaningful linear regression model for the women that would predict who, among all the women in our study, would attend more often. So it is very interesting to see that we were able to find a meaningful model using the subset of women who voluntarily took the H/S/R assessment at intake. Table 5 shows that three variables helped to predict which women would attend more frequently (R2 = 0.261). These included the importance of religion or spirituality in their daily life (at time of assessment), the more they listened to religious programs on television or radio in the previous six months, and race (non-Whites attended more often than Whites).

Linear Regression Model Predicting Number of Attendances for Women Who Took an H/S/R Assessment at Intake.

Conclusions

In this paper we argue that the correctional system in the United States needs to take the humanist, spiritual, and religious self-identities of inmates seriously, and do all it can to foster and support those self-identities, or ways of making meaning. The meta-analytic findings from the studies commissioned by the American Psychological Association, together with the findings from ethnographic and some recidivism studies in prison, suggest that H/S/R pathways to meaning may be an important part of the evidence-based principle of responsivity, as well as the desistance process. The sociology of the H/S/R involvement of 349 women and 3,009 men during the first year of their incarceration in the Oregon prison system, and the extended pro-social network of chaplains, other staff and volunteers uncovered by our study, reveal a diverse and widespread human, social and spiritual capital that is naturally supportive of H/S/R responsivity and the desistance process for thousands of men and women in prison. In our view it is in the best interest of a more humane, effective, and less costly correctional system, not only to foster this capital, but also to integrate it more closely into the programming and treatment aspects of the correctional process.

References

- A. Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York, NY, USA: First Ballantine Books Edition, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- W.R. Miller, and J.C.D. Baca. Quantum Change: When Epiphanies and Sudden Insights Transform Ordinary Lives. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press, 2001, p. 212. [Google Scholar]

- M. Marable. Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. New York, NY, USA: Viking Adult, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- C. Colson. Born Again. Grand Rapids, MI, USA: Chosen Books, 1976. [Google Scholar]

- S. Maruna, L. Wilson, and K. Curran. “Why god is often found behind bars: Prison conversions and the crisis of self-narrative.” Res. Hum. Dev. 3 (2006): 161–184. [Google Scholar]

- T.R. Clear, and M.T. Sumter. “Prisoners, prison, and religion: Religion and adjustment to prison.” J. Offender Rehabil.35 (2002): 127–159. [Google Scholar]

- T.R. Clear, B.D. Stout, H. Dammer, L. Kelly, P. Hardyman, and C. Shapiro. Prisoners, prisons, and religion: Final report. New Brunswick, NJ, USA: School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, 1992, pp. 1–108. [Google Scholar]

- H.R. Dammer. “Piety in Prison: An Ethnography of Religion in the Correctional Environment.” Ph.D. dissertation, Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, Newark, NJ, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- H.R. Dammer. “The reasons for religious involvement in the correctional environment.” J. Offender Rehabil. 35 (2002): 35–58. [Google Scholar]

- M.T. Sumter. “Religiousness and Post-release Community Adjustment.” Ph.D. Dissertation, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- T.R. Clear, P.L. Hardyman, B. Stout, K. Lucken, and H.R. Dammer. “The value of religion in prison: An inmate perspective.” J. Contemp. Crim. Justice 16 (2000): 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- F.T. Cullen, J.L. Sundt, and J. Wozniac. The virtuous prison: Toward a restorative rehabilitation. In Contemporary Issues in Crime and Justice: Essays in Honor of Gilbert Geis. Edited by H. Pontell, and D. Shichor. Saddle River, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- S. Aos, M. Miller, and E. Drake. Evidence-based Adult Corrections Programs: What Works and What Does Not. Washington State Institute for Public Policy. January; 2006, p. 21. [Google Scholar]

- R.J. Wilson, F. Cortoni, and A.J. McWhinnie. “Circles of support & accountability: A canadian national replication of outcome findings.” Sex. Abuse J. Res. Treat. 21 (2009): 412–430. [Google Scholar]

- B.R. Johnson. More God Less Crime: Why Faith Matters and How It Could Matter More. West Conshohocken, PA, USA: Templeton Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- T.P. O’Connor, and J.B. Duncan. “Religion and prison programming: The role, impact, and future direction of faith in correctional systems.” Off. Prog. Rep. 11 (2008): 81–96. [Google Scholar]

- K.D. Dodson, N. Leann, and P.M. Klenowski. “An Evidence-Based Assessment of Faith-Based Programs; Do Faith-Based Programs “Work” to Reduce Recidivism? ” J. Off. Rehab. 50 (2011): 367–383. [Google Scholar]

- J. Bonta, and D. Andrews. Viewing offender assessment and rehabilitation through the lens of the risk-needs-responsivity model. In Offender Supervision: New Directions in Theory, Research and Practice. Edited by F. McNeill, P. Rayner, and C. Trotter. New York, NY, USA: Willan Publishing, 2010, pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar]

- J.C. Norcross, and B.E. Wampold. “What works for whom: Tailoring psychotherapy to the person.” J. Clin. Psychol. 67 (2010): 127–132. [Google Scholar]

- E.L. Worthington, J.N. Hook, D.E. Davis, and M.A. McDaniel. “Religion and spirituality.” J. Clin. Psychol. 67 (2011): 204–214. [Google Scholar]

- B.A. Kosmin, and A. Keysar. American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS 2008): Summary Report. Hartford, CT, USA: Trinity College, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- B.J. Zinnbauer, K.I. Pargament, B. Cole, M.S. Rye, E.M. Butter, T.G. Belavich, K.M. Hipp, A.B. Scott, and J.L. Kadar. “Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy.” J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 36 (1997): 549–564. [Google Scholar]

- T.P. O’Connor, J. Duncan, and F. Quillard. “Criminology and religion: The shape of an authentic dialogue.” Criminol. Publ. Pol. 5 (2006): 559–570. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman vs. McCaughtry. US Court of Appeals. Chicago, IL, USA: Seventh Circuit. August; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- C. Taylor. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA, USA: Harvard University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- J.A. Beckford, and S. Gilliat. Religion in Prison: Equal Rights in a Multi Faith Society. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- R.D. McConnell. “The penitentiary: Prison control and the genesis of prison religion, self-control in a total institution.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Virginia, Dillwyn, VA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- S. Maruna. Making Good: How Ex-convicts Reform and Rebuild their Lives. Washington, DC, USA: American Psychological Association, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- T.P. O’Connor. “What works, religion as a correctional intervention: Part i.” J. Community Correct. XIV (2004). [Google Scholar]

- T.P. O’Connor. “What works, religion as a correctional intervention: Part ii.” J. Community Correct. XIV (2005). [Google Scholar]

- T. O ‘Connor, J. Duncan, S. Lazzari, and J. Lehr. Prisoners, Chaplains and Volunteers in Oregon:Diverse and Widespread Human, Social and Spiritual Capital for Desistance. Washington, DC, USA: American Societyof Criminology, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Oregon Department of Corrections Transitional Services Division: Religious Services. Available online: http://www.oregon.gov/DOC/TRANS/religious_services/rs_home_page.shtml (Accessed on 4 May 2011).

- T.P. O’Connor, T. Cayton, S. Taylor, R. McKenna, and N. Monroe. “Home for good in Oregon: A community, faith, and state re-entry partnership to increase restorative justice.” Correct. Today 66 (2004): 72–77. [Google Scholar]

- Maharishi Foundation USA. “Being” behind bars. In Enlightenment: The Transcendental Meditation Magazine. Fairfield, IA, USA: Maharishi Foundation, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- M. Thigpen. Message from the Director: Service. Washington, DC, USA: National Institute of Corrections Newsletter. September; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- T. O ‘Connor, J. Lehr, S. Lazzari, and J. Duncan. Prison and Re-entry Volunteers: An Overlooked, Creative and Cost Effective Source of Human Capital for Desistance. Washington, DC, USA: American Society of Criminology, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Inside-Out Prison Exchange Program. Available online: http://www.insideoutcenter.org/home.html (Accessed on 12 October 2011).

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. In U.S. Religious Landscape Survey—Religious Affiliation: Diverse and Dynamic. Washington, DC, USA: PEW Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008.

- T.P. O’Connor, D. Hoge, and E. Alexander. “The relative influence of youth and adult experiences on personal spirituality and church involvement.” J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 41 (2002): 723–732. [Google Scholar]

- D.A. Roozen. “Church dropouts: Changing patterns of disengagement and re-entry.” Rev. Relig. Res. 21 (1980): 427–450. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. In U.S. Religious Landscape Survey: The Stronger Sex— Spiritually Speaking. Washington, DC, USA: PEW Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008.

- R. Stark. “Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender differences in religious commitment.” J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 41 (2002): 495–507. [Google Scholar]

- A. Beck, D. Gilliard, L. Greenfeld, C. Harlow, T. Hester, L. Jankowski, T. Snell, J. Stephan, and D. Morton. Survey of State Prison Inmates, 1991. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Department of Justice, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- R. Gorsuch, and G. Venable. “Development of an “age universal” i-e scale.” J. Sci. Stud. Relig. 22 (1983): 181–187. [Google Scholar]

A. Haley. The Autobiography of Malcolm X. New York, NY, USA: First Ballantine Books Edition, 1973. [Google Scholar]

© 2011 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open-access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/).