The Impact of a Volunteer Prison Ministry Program on the Long-term Recidivism of Federal Inmates

Young, M., Gartner, J., O’Connor, T., Larson, D., & Wright, K. (1995). The Impact of a Volunteer Prison Ministry Program on the Long-term Recidivism of Federal Inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 22(1/2), 97-118

The Impact of a Volunteer Prison Ministry Program on the Long-term Recidivism of Federal Inmates

MARK C. YOUNG

Fallston, Maryland

JOHN GARTNER

School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University

THOMAS O’CONNOR

Center for Social Research

DAVID LARSON, M.D.

Media Center, Duke University

KEVIN WRIGHT

State University of New York at Binghamton

ABSTRACT

This study investigated long-term recidivism among a group of federal inmates trained as volunteer prison ministers. Inmates were furloughed to Washington, D.C., for a two-week seminar designed to support their religious faith and develop their potential for religious leadership with fellow inmates in a program operated by Prison Fellowship Ministries, a volunteer organization which ministers to offenders and ex-offenders, and supported by the Federal Bureau of Prisons. Recidivism data for seminar participants (n = 180) were compared to data drawn from a matched control group (n = 185) over an eight to fourteen year follow-up period. Chi-square analysis revealed that the seminar group had a significantly lower rate of recidivism than the control group. Logit analysis was employed to explore the finding of lower rates of recidivism in greater detail_ Survival analysis showed that the seminar group maintained a higher survival rate during the study period than the control group. Seminars were most effective with lower risk subjects, white subjects, and especially women. The findings suggest that religious programming may contribute to the long-term rehabilitation of certain kinds of offenders. [Article copies available from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-342-9678.]

A historical link exists in America between religious ideals and the use of prisons to rehabilitate criminals. The rehabilitative concern can be traced back to the earliest attempts in post-revolutionary America to deal with crime. Led largely by religious organizations like the Quakers of Pennsylvania, early reformers viewed the move toward incarceration as an opportunity to rehabilitate criminals rather than merely punish them (Wright, 1987). Religious thought and values had a great deal of influence on the developing prison system and helped to give the system a sense of meaning and “normative coherence” (Scotnicki, 1992). Even today, most prisons in the United States provide religious programming through the activity of chaplains or volunteer organizations. Typically, prisons reflect the religious diversity of the larger society. Chaplains and/or worshipping groups serve various Christian, Jewish, Muslim, and Native American faiths. Prisons provide religious opportunities to meet offenders’ fundamental constitutional rights, and many administrators view religious faith as helpful to inmates in times of need and stress.

The depth of the historical and contemporary role of religion in the American penal system suggests that the study of religion in prisons is an important factor in attempting to understand the efforts of the penal system to rehabilitate offenders.

What cannot be denied is that religion is a topic that should be of interest to those concerned with the field of corrections. Religious programming is the single most common form of institutional programs for inmate management and rehabilitation, and it is one of the very few prison programs to which inmates have a right. Indeed, in the United States, the history of incarceration is intimately intertwined with religious movements (Clear, 1991).

THE NEGLECT OF THE STUDY Of RELIGION IN PRISONS

Reviews of the literature indicate that religion has been neglected empirically in such fields as psychiatry (Larson, Pattison, Blazer, Om-ran, & Kaplan, 1986), sociology (Buehler, Hesser, & Weigert, 1983), geriatrics (Larson, Lyons, Huckeba, Gottlieb, & Beardsley, 1988), and family practice (Craigie, Liu, Larson, & Lyons, 1988). Most germane to this study is the neglect of religious variables in criminal justice research relative to rehabilitation and recidivism (Johnson, 1984; Gart-ner, O’Connor, Larson, Young, Wright, & Rosen, 1990).

Johnson (1984) conducted an extensive review of the literature relative to the role of religion in behavioral deviancy. He found a host of studies that examined the religion-deviancy relationship in a variety of ways. Most of the empirical studies dealt with juvenile delinquency and based their data on self reports and percentage comparisons. The researchers sought to discover the degree to which religion might act as a social control mechanism in preventing delinquency and criminal activity.

Johnson (1984) noted two areas of neglect in the literature: (1) the lack of research dealing with religious involvement or commitment as a means of rehabilitation, and (2) the investigation of religious involvement among adult prison inmates. In summary, Johnson writes, “The question of whether rehabilitation and treatment of offenders is enhanced by religious training is an empirical question which has not yet been examined” (1984:13).

Gartner et al. (1990) also conducted a systematic review of scientific journals in the sociological, psychological, and criminal justice literatures. Gartner et al. included only empirical studies on the rehabilitation and recidivism of adults in their review. Their findings indicated that criminal justice researchers studied religious commitment vari-ables infrequently. When religious variables were studied, the investigations used them in only a peripheral manner such as noting denominational affiliation. Quite significantly, no study made religion its primary focus. Gartner et al. write, “There is almost a complete absence of research on the relationship between religion and religious rehabilitation programs with recidivism. Such research would help advance the scientific study of religion” (1990:15).

In review articles on criminal recidivism any discussion of religion is conspicuous only by its absence. In Martinson’s highly cited review of 231 rehabilitation studies from 1945 to 1967 no mention was made

of religion as a rehabilitative intervention (1974). Nor was any mention made of religion in a previous review of 100 rehabilitation studies by Bailey (1966). Furthermore, in a more recent quantitative systematic analysis of seventy-one studies on the relationship between twenty-three potential biographical predictors and recidivism, religion as an independent variable was not included (Prichard, 1979).

This absence of research on the rehabilitative effect of religion on adult offenders is surprising given that religious involvement has been found to be positively associated with social conformity and with adjustment within prison. Geographical areas with high rates of church membership produce lower rates of crime (Stark, 1980). Juveniles who live in areas with high levels of church involvement and who participate in the church they belong to are less likely to be delinquent than those juveniles who do not participate in their church (Stark, 1982). Adult prison inmates with high levels of religious involvement have lower rates of depression and in-prison disciplinary infractions than other inmates (Clear, 1992).

A recent review of the mental health literature found a consistent negative relationship between religious behavior and social deviance. This review distinguished religious behavior from religious attitudes which did not correlate with deviant behavior (Gartner, Larson & Allen, 1991).

The present study concentrates on the relationship between Chris-tian religious involvement and criminal rehabilitation. Specifically, the study looks at the long-term impact of a prison ministry program known as the Washington, D.C. Discipleship Seminars on adult criminal recidivism. These Seminars were sponsored and run by Prison Fellowship Ministries.

Prison Fellowship Ministries was founded in 1975 by Charles W. Colson, a former presidential aide to Richard M. Nixon, following his own incarceration in Federal prison on a conviction of obstructing justice. Prison Fellowship is a Christian organization with over 45,000 volunteers who serve in prisons throughout the United States and in 34 countries around the world. Prison Fellowship has a range of programs which provide support and practical assistance to offenders, ex-offenders and their families.

The Washington D.C. Discipleship Seminars were selected for study for a number of reasons. First, the program involved Federal prisoners and had a nationwide scope. Secondly, Prison Fellowship was interested in an evaluation of the effectiveness of the Seminars and was willing to provide information and resources to make the study possible. Finally, a small pilot study (Ames, 1990) indicated that the Discipleship Seminars might be having a positive effect on the rate of recidivism for those who participated.

METHODOLOGY

To evaluate the long-term effectiveness of the Washington, D.C. Discipleship Seminars, recidivism data of a sample population of seminar participants were compared to data drawn from a matched control group. Both groups included offenders released from Federal prisons as parolees, mandatory releasees, or sentence expirees. The study was guided by two hypotheses:

- A smaller percentage of the Prison Fellowship group members will become recidivists as compared to the control group; and

- Those in the Prison Fellowship group will survive crime-free for a longer period of time following release from prison than those in the control group.

In addition to testing the two hypotheses, the investigators were interested in exploring the interaction effects between group membership and four control variables: gender, race, age at release, and the salient factor score.

Sample Selection

Between November, 1975 and November, 1986 Prison Fellowship conducted fifty-nine Discipleship Seminars in Washington, D.C. (In-prison seminars have since replaced the Washington sessions.) During these seminars small groups (n = 6-15) of Federal prison inmates from institutions across the United States were furloughed to the Washing-ton, D.C. area to participate in an intensive two week-long ministry program.

The two week-long gathering was aimed at deepening the prisoners’ Christian faith and preparing them to provide Christian fellowship and support to their fellow inmates within their respective institutions. The inmates were chosen for the program after being recommended for it by their prison chaplain. Inmates were selected for the program on the basis of their leadership qualities and religious commitment.

In an atmosphere of support and fellowship the inmates participated in devotional sharing, worship experiences, small group discussions, individual prayer time, Bible study, and leadership training workshops. They also participated in various functions in Washington, D.C., including interaction with various groups from local churches and schools. The seminar participants had opportunities to meet with members of Congress and other government officials. Most notable was the opportunity for most of the seminar groups to meet with Norman Carlson, then the Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons.

Subjects for the Prison Fellowship group participated in any of the first 21 Discipleship Seminars conducted between November, 1975 and November, 1979 (n = 230). Prison Fellowship provided listings of these persons along with archival information (Ames, 1990). The records and archival data contained the following information for each of the program participants: names, dates of birth, dates of release, F.B.I. identification numbers, race, gender, and the 1976 version of the U.S. Parole Commission salient factor scores (Hoffman & Adelberg, 1980; Hoffman & Beck, 1976). The information was cross-referenced with records of the Federal Bureau of Prisons, United States Parole Commission, or the Federal Bureau of Investigation to maximize accuracy.

Of the original 230 participants, 16 persons were eliminated because no criminal justice records could be found for them. An additional 7 persons were eliminated because data for all four matching variables could not be located. Another 17 persons were eliminated because their release dates surpassed the cut-off date of December 31, 1980 established for the study. After these various eliminations, 190 subjects were left in the Prison Fellowship group.

The control group was selected from a cohort of 2,289 Federal inmates representing a fifty percent random sample of all prisoners receiving commitment sentences of more than one year and one day who were released to the community during the first six months of 1978. This cohort was established for a previous study conducted by the U.S. Parole Commission (Hoffman, 1983). The matching procedure selected control subjects using a stratified proportional probability sampling method that replicated the characteristics of the experimental group with respect to race, gender, age at release, and the 1976 version of the salient factor score. Proportional random selection from each permutation of the sample design variable was employed.

The stratification process created 48 cells by dividing the control variables as follows: race into two groups (white and black); gender into two groups (male and female); age at release into three groups (18-25 years, 26-35 years, 36 years and older); salient factor score into four groups (poor risk scores of 1-3, fair risk scores of 4-5, good risk scores of 6-8, very good risk scores of 9-11). There were no salient factor scores of zero in the Prison Fellowship group so this study did not include the zero score in the stratification.

The two groups differ with respect to the issues of self-motivation and selection into the program. Those in the Prison Fellowship group volunteered for participation in the ministry program and they also went through a selection process. These issues represent motivational and selection factors which pose a limitation on the interpretation of results. Such limitations are common to social science research and are especially difficult to avoid in research involving prison programming. Within the limits of the available data on each program participant, every effort was made in the research design to reduce the confounding effect of motivation and selection on the findings of the study.

Data Collection

Data collection was accomplished through cooperation of the U.S. Parole Commission and the Identification Division of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Records of Arrest (RAP sheets) were accessed and copied through either the National Crime Information Center’s computer system or the manual files. Of the total number of subjects, 180 of the 190 Prison Fellowship RAP sheets were located, and 185 of the 190 control RAP sheets were located. The fifteen subjects for whom no RAP sheets could be located were dropped from the study.

Once the Records of Arrest were obtained, the following items were coded from them for each subject:

- the subject’s release date;

- the crime type of the arrest offense that originally incarcerated the subject;

- the severity rating of the original offense;

- the date of the first arrest (if any) following release from prison;

- the date of the RAP Sheet.

To code the crime type and rate the severity of the original offenses, this study utilized the guidelines delineated by paragraph 2.20 of the U.S. Parole Commission Rules (U.S. Parole Commission Paroling Policy Guidelines: 28 C.F.R. 2.20 and accompanying Notes and Procedures, 1984). The rules are detailed and fairly straightforward in utilization. Two members of the research team corroborated in coding approximately 25% of the subjects to establish consistency of utilization of the rules. Once the team established a consistent utilization of the rules the data for the remaining subjects was coded by one of the team members.

The criterion measure of recidivism for this investigation was defined as any new arrest record including parole violations following release from prison through the duration of the study period. Thus, favorable outcome would mean the absence of any new arrest data on the RAP Sheet following the time point of prison release. The actual study periods varied for each subject depending on the date of release. All study periods were long term ranging from eight to fourteen years.

The use of rearrest as the criterion measure of recidivism involves the possibility of both false positive error and false negative error. Ex-convicts are prone to be rearrested on suspicion even though they may not have returned to a life of crime. Conversely, many of those who do return to criminal behavior may go undetected or unarrested. Thus, our measure of recidivism may not be an accurate representation of actual recidivism. However, the likelihood of such errors is equivalent for both groups in the study.

Additionally, while F.B.I. RAP sheets represent the most consistent data available, they do not always record arrests from all jurisdictions. Thus, the arrest data may not be completely accurate and valid. Again, however, there is no reason to question the equivalence of validity between the two groups.

Methods of Analysis

As noted earlier, this study was guided by two hypotheses, each with its own dependent variable. Descriptive statistics and appropriate uni-variate or multivariate analyses were utilized for these dependent variables. All analyses were generated using either SPSS-X or SPSS/ PC+.

Hypothesis 1

The dependent variable for Hypothesis I involved the percentage rate of recidivism for each group during the time period of the study. The hypothesis predicted a smaller percentage of recidivism for the Prison Fellowship group as compared to the control group. This percentage rate was analyzed using the chi-square test with a significance level of .05.

To explore the factors influencing the recidivism rates, logic analysis was employed. The following categorical variables were entered to generate the saturated model with recidivism (yes or no) as the dependent variable: group, gender, race, age at release collapsed into two categories (age ≤ 35 or age ≥ 36), and salient factor score collapsed into two categories (high risk ≤ 5 or low risk ≥ 6).

Two continuous variables were also entered as co-variates: “window” and “time-out.” Window is a time variable used to control for the varying study periods of the individual subjects. Window was calculated in years by subtracting the date of the subject’s release from prison from the date the RAP sheet was retrieved. It was necessary to calculate this variable because the rap sheets were obtained at two different points in time over a six month period.

Time-out is also a time variable used to control for the varying periods of street time for an individual subject prior to first arrest. Time-out was calculated in years by subtracting the date of the subject’s release from prison from the date of first arrest. If the subject was not a recidivist, then time-out was equal to window.

Hypothesis 2

The dependent variable for Hypothesis 2 represents crime-free survival time following release from prison as generated utilizing survival analysis. The hypothesis predicted that those in the Prison Fellowship group would survive for a longer period of time following release than those in the control group.

The hypothesis was tested by analyzing time to first arrest by group membership through fourteen years in intervals of one-half year. A comparison of the two groups is generated using the Lee-Desu Statistic D with a significance level of .05. The analysis also generates a graph of the cumulative proportion surviving over time.

The study further examined the crime free survival time by group by utilizing the following variables as control variables: risk level collapsed into two categories (high risk was defined as SFS ≤ 5; low risk was defined as SFS ≥ 6); race as white or black for men only (there were insufficient numbers of women for survival analysis); and window collapsed into two categories (window ≤ 12 years or window > 12 years).

Investigation of the interactions among the independent variables was conducted to pinpoint specific sub-groups for whom the program was effective. It is generally accepted in criminal justice research that no program works for all populations of prisoners in all circumstances. Therefore, it is necessary to identify the interactional effects among programs, persons, and situations.

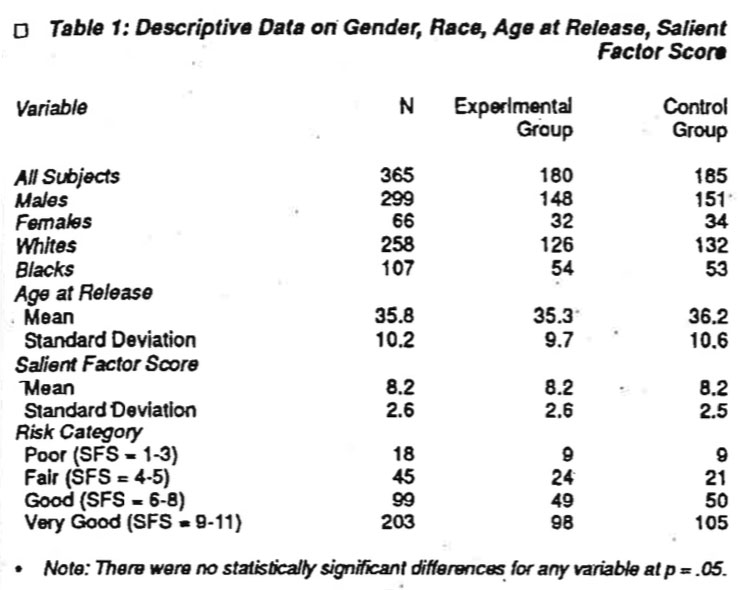

Description of the Sample

Table 1 summarizes the descriptive statistics of the two groups with respect to the four matching variables: race, gender, age at release, and salient factor score (SFS). The matching procedures successfully produced a matched control group. Chi-square analyses confirmed parity in race and gender, and T-analyses confirmed parity in age and SFS.

With respect to crime type for the original incarcerating offenses, both groups spanned the gamut of possible crimes. To summarize, crimes involving drugs and narcotics were the most frequent type for the overall study and within each separate group (38%, or 135/353). The second highest frequency for crime type involved theft and related offenses including general theft, automobile theft, fraud, forgery, interstate transportation of stolen property. and possession of stolen goods (31%, or 109/353). The next highest crime type was robbery (13%, or 49/353). All other offense types had frequencies of less than 10 each in the overall study.

In terms of severity of crime, the original offense types were rated on a crime severity scale as noted previously. This scale ranges from 1 to 8 in whole integers with 1 being the least severe crime. The mean severity score for the overall study was 3.79 with a standard deviation of 1.5. The mean severity score for the Prison Fellowship group was 3.98 with a standard deviation of 1.43. The mean severity score for the control group was 3.6 with a standard deviation of 1.54. To be clear, the Prison Fellowship group had the higher mean severity score. T-analyses revealed that the difference between the two groups with respect to mean severity score was significant at .02 (t = 2.36, two-tailed; d.f. = 351).

RESULTS

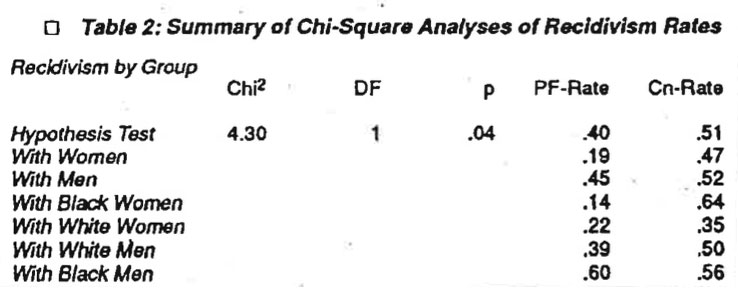

Hypothesis 1

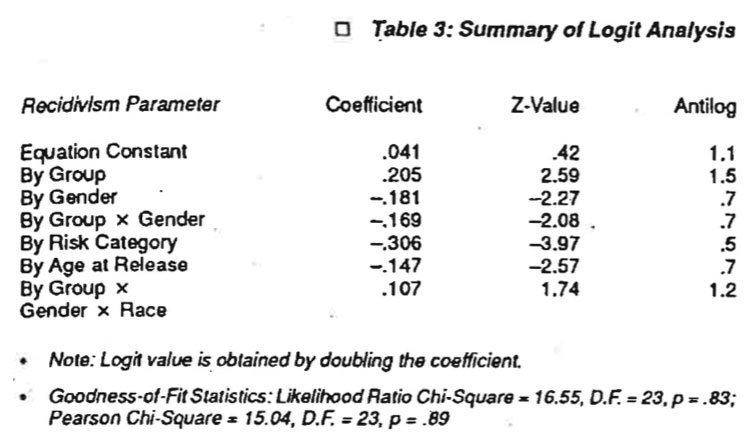

The findings support this hypothesis. Testing recidivism by group resulted in a chi-square value of 4.30 (d.f. = 1, significance = .04). The between group difference was in the predicted direction. The Prison Fellowship group had a recidivism rate of .40 (72 of 180) while the control group had a recidivism rate of .51 (94 of 185). Breaking down the recidivism rates by gender and race, Table 2 reveals that the Prison Fellowship group had lower rates for each permutation except with black men. Controlling for gender revealed that women benefitted more than men from the Discipleship Seminars. The Prison Fellowship women had a recidivism rate of only .19 compared to .47 for the control women. The Prison Fellowship men had a recidivism rate of .45 as compared to .52 for the control men. Logit analysis was employed to explore the factors influencing the recidivism rates in a more refined manner. The goodness-of-fit statistics reveal that the final model predicts the probability of recidivism effectively. The Likelihood-ratio chi-square is 16.55 (d.f. = 23, p .83). The Pearson chi-square is 15.04 (d.f.= 23, p = .89). Table 3 summarizes the data for the final design model of the logit analysis. Using the antilogs of the multiplicative equation, we can compare the influence of the significant design variables on the odds of recidivism. Other factors being equal, we can make the following statements:

- If one is in the Prison Fellowship group, the odds of recidivism are I to 1.5 as compared to being in the control group;

- If one is female, the odds of recidivism are .7 to 1 as compared to being male;

- If one is in the Prison Fellowship group and is female, the odds of recidivism are yet even smaller than .7 to 1;

- If one is in the low risk category (SFS 6-11), the odds of recidivism are .5 to I as compared to the high risk category (SFS 1-5); and

- If one is in the older age category (z 36) at release, the odds of recidivism are .7 to 1 as compared to being in the younger age category (535).

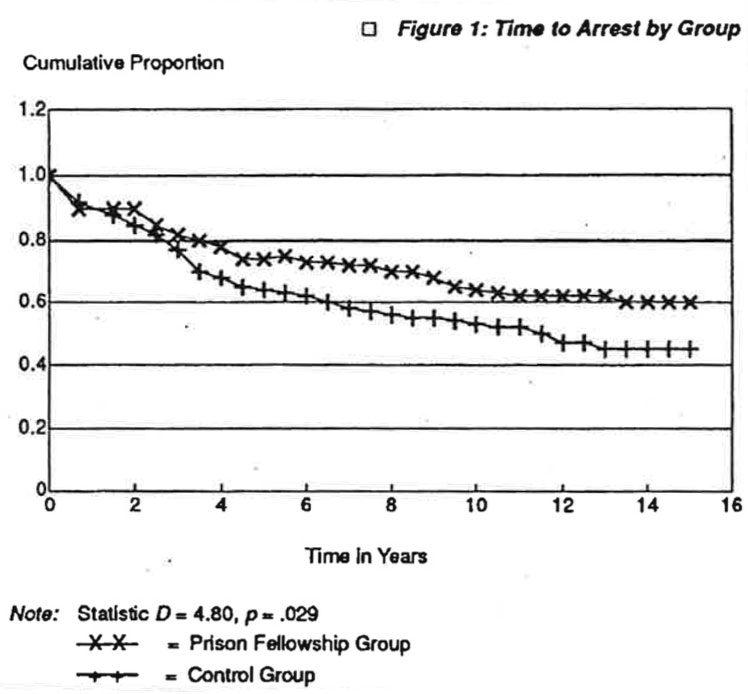

Hypothesis 2

The findings of this study also support the second hypothesis. The overall comparison statistic D analyzing time to arrest by group was 4.80 (p = .029). Figure 1 displays the plot of the cumulative proportion surviving in each group at six month intervals. The two lines clearly diverge with a higher proportion of the Prison Fellowship group surviving throughout the time period.

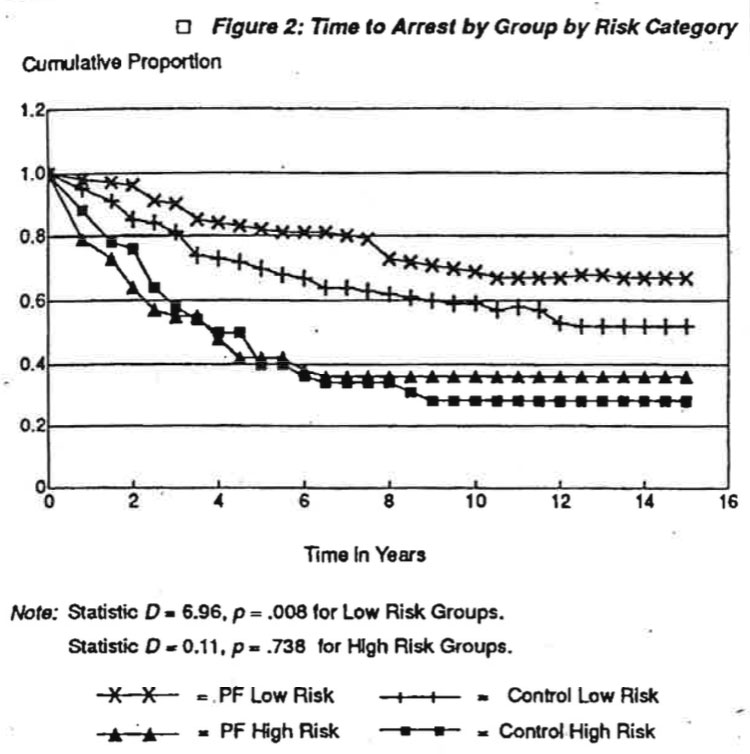

Survival analysis was also utilized to explore the influence of risk category by group and the influence of race for male subjects by group. Survival analysis exploring the influence of the window variable (as described previously) had no significant results. The overall comparison statistic D analyzing time to arrest by group by window was 0.0, with p = .99. The findings revealed a significant effect on survival time with respect to the risk category and group interaction. The overall comparison statistic D for the time to arrest by group for low risk subjects (SFS z 6) was 6.96 (p = .008). The overall comparison statistic D for the time to arrest by group for high risk subjects (SFS 5 5) was .11 (p = .738). Thus, there was a significant difference between groups at the .05 level of confidence for the low risk subjects, but not for the high risk individuals.

Figure 2 displays the plot lines of the cumulative proportion surviving at six month intervals for the high and low risk subjects by group. The two lines for the low risk subjects clearly diverge with the Prison Fellowship group surviving at a higher proportion than the control group. The two lines for the high risk subjects co-mingle throughout the study period signifying no difference between groups. Notably, all of the low risk subjects outperformed all of the high risk subjects.

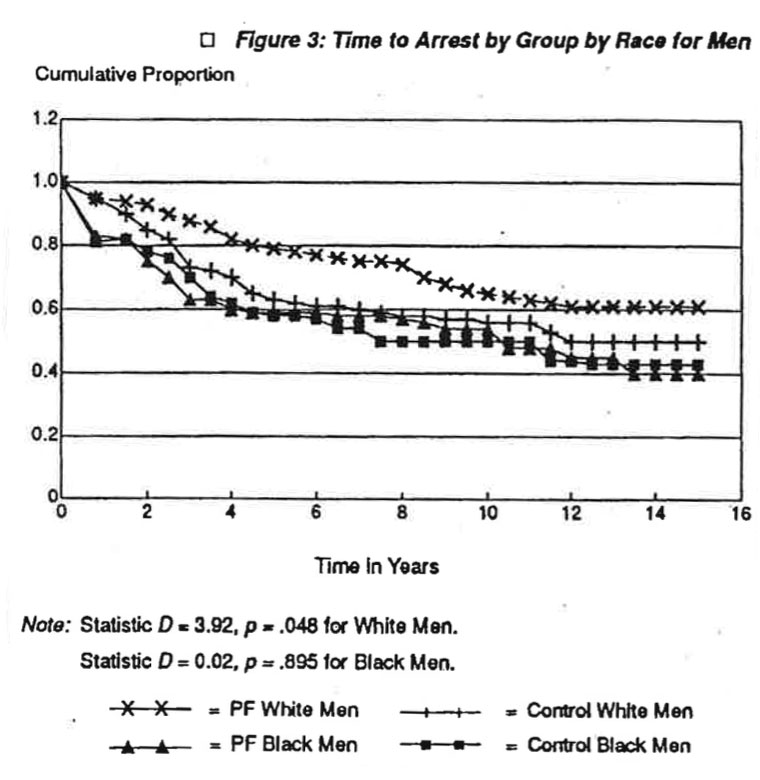

Selecting only male subjects. the analysis reveals a significant effect with respect to the interaction between race and group. The overall comparison statistic D for the time to arrest by group for white males was 3.92 (p = .048). The overall comparison statistic D for the time to arrest by group for black males was .02 (p = .895). Thus, there was a significant difference between groups at the .05 level of confidence for the white males, but not for black males.

Figure 3 displays the plot lines of the cumulative proportion surviving at six month intervals for white and black males by group. The two lines representing the white men clearly diverge with the Prison Fellowship group surviving at a higher proportion throughout the time period than the control group. The lines representing the black men co-mingle throughout the time period signifying no difference between the groups.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study support both of the research hypotheses. A significantly smaller percentage of the participants in the Discipleship Seminars became recidivists as compared to the members of the control group. The Prison Fellowship subjects also were arrested at a slower rate following release from prison than those in the control group. Thus, the Prison Fellowship group maintained a higher survival rate for a longer period of time than the control group.

Based on these results, it appears that there may be a significant link between participation in the Discipleship Seminars of Prison Fellowship Ministries and a rehabilitative effect with respect to criminal behavior. The Discipleship Seminars were designed to foster religious commitment and fellowship and to integrate the inmates with a wider support network in the community at large. It is possible that such religious commitment, fellowship and social integration promoted restructuring within individual prisoners producing a treatment effect. The Christian Church is an important institution in the lives of many Americans and the development of adult social bonds among offenders to socializing institutions has been shown to have a positive effect on criminal behavior (Sampson & Laub, 1992). Furthermore it is possible that the strong ethical and moral tone of Christianity may have fostered rehabilitation and a movement away from criminal activity—it is a tenet of Prison Fellowship that “crime is a moral problem.”

There are three alternative explanations of the observed results: (1) a Hawthorn effect; (2) a selection effect; and (3) a self-motivation or self-selection effect.

The results could be due to a Hawthorn effect and not to a religious effect per se. The Discipleship Seminars included a wide array of experiences, many of which involved special attention and special treatment of the prisoners. The prisoners were furloughed from their respective institutions and traveled to Washington, D.C. They met with various members of Congress and other governmental agencies. Many of the participants met with Norman Carlson who was then the director of the Bureau of Prisons. It is possible that these factors produced the variance in recidivism and survival time.

However, it seems unlikely that this effect would persist for many years after the program and exert a significant effect on recidivism.

The original Hawthorn effect documented the effect of observants on worker’s productivity at the time the workers were being observed, not years afterward. More serious doubts perhaps are cast on the findings of this study by the fact that the members of the Prison Fellowship group were chosen for participation in the Discipleship Seminars based on independent assessments of their leadership potential and Christian behavior and were also self-motivated to participate in the program. It is possible that this screening process produced an experimental group more likely to succeed than the matched control group. It is also possible that by volunteering, these persons were motivated to change in ways that do not necessarily involve religion.

Every effort was made to make the control group similar to the experimental group on the known variables available to the research team, however, the fact that we did not know if the control group met the selection criteria or were equally self-motivated means that the experimental and control groups may have differed from each other in ways other than participation in the Prison Fellowship program and that these other differences were what accounted for the differences in their rates of recidivism and survival.

A careful matching procedure was used to reduce differences between the Prison Fellowship group and the general population on known variables. In addition statistical procedures were used to control for factors other than PF participation which might differentiate experimental subjects from the control subjects. These design and statistical methods do reduce but do not entirely remove the inconclusive nature of the findings which are due to the fact that the subjects were both selected and self-selected themselves into the program. Practical restrictions on available data, the retrospective nature of the study, and the difficulty of randomly assigning subjects to religious programs prevented this particular study from arriving at more definite findings.

Even though there are limitations to the findings of this study, it is arguable that they represent a development in our understanding of the influence of religious involvement on adult offenders. Despite their limitations, the findings of this study are intriguing, they point towards the potentially rehabilitative nature of the religious involvement of adult offenders. These findings are grounds for future studies.

Analyses of the findings for the sub-groups within the study also elicited some important information and suggested that some sub-groupings evidenced more positive changes in association with the Discipleship Seminars than others. A review of the empirical literature on criminal rehabilitation suggests this is consistent with findings relative to other rehabilitation programs (Martinson, 1979; Palmer, 1975, 1983; Andrew et al., 1990). No programs work for everyone, rather sonic programs work for some people in certain circumstances.

The Discipleship Seminars were effective with the low risk subjects, but not with the high risk subjects. By definition the probability of recidivism was lower for low risk subjects as a whole. The survival analysis, however, indicated that the Prison Fellowship subjects in this category maintained a higher survival rate for a longer period of time than the controls. Further research is needed to clearly explain this finding. Perhaps the lower risk subjects were more amenable to the religious nature of the treatment.

Black men did not appear to evidence any positive changes associated with participation in the Discipleship Seminars. The Prison Fellowship subjects in this category became recidivists at a slightly higher rate than the black men in the control group. Survival analysis revealed they also became recidivists as quickly.

This finding may be related to the fact that in the early days of Prison Fellowship, their programs may have been based on a religious style more familiar to white Americans. Black men may have had a difficult time identifying with the program.

A more likely explanation of this finding involves other factors associated with race. It is possible, for example, that the black male subjects were released into environments or circumstances that mitigated against a crime-free life more strongly than for those of the other subject categories. For example, black males in the United States typically have higher unemployment rates than other groupings, and often are more frequently exposed to potential drug and alcohol abuse.

Perhaps the greatest surprise in the findings was the large difference between men and women. Women who participated in the Discipleship Seminars demonstrated a drop in recidivism four times greater than that evidenced by Prison Fellowship men when compared to their respective controls. The difference between the rates of the Prison Fellowship women and the control women was .28. The difference between the two groups of men was only .07. Given the relatively small number of women in the sample, this finding must be interpreted with some caution. However, women as a group show higher levels of religious participation than men, and thus may be more influenced by religious rehabilitation efforts.

It is important to note that this study was a long-term investigation. One frequent criticism of the effect of religious experience on behavior is that it does not endure. These findings suggest that the reductions in recidivism associated with participation in the Discipleship Seminars are sustained over long periods of time. Insofar as the variance can be explained by a treatment effect, the results of this research contradict this criticism.

The results of this investigation certainly suggest that religious ministry may serve a significant rehabilitative purpose in criminal justice and is worthy of further research. Such research should compare the relative effectiveness of differing religious programs for various populations. Future research should also aim to overcome the problems which selection criteria and self-motivation cause for the findings of observational studies. Research should also address the relative effectiveness of varying levels of religious involvement. Studies involving larger groups of women will be especially important as this investigation suggests they may participate more intensively than men in religious programming to greater positive effect.

From a social policy perspective it is important to note that this was a volunteer-run program supported by the Christian community. This kind of program is capable of being a bridge that safely links inmates and the larger community even within the context of the correctional system. Furthermore, the main costs of the program were not paid for by the Federal justice system. Volunteer-run religious programs which are capable of drawing upon the resources of the wider community and demonstrating a beneficial effect may well be a potent and a cost-effective resource in the national effort to reduce the negative effects of crime on individuals and the community.

REFERENCES

Andrew, D.A., Zinger, 1., Hoge, R., Bonta, J., Genreeau, P., Cullen, F. 1990. Does Correctional Treatment Work? A Clinically-Relevant and Psychologically-Informed Meta-Analysis, Criminology, 57:153-160.

Ames, D.B., Gartner, J., O’Connor, T. 1990. Participation in a Volunteer Prison Ministry Program and Recidivism. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, Massachusetts.

Bailey, W.C. 1966. Correctional outcome: An evaluation of 100 reports. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology and Police Science, 57:153-160.

Buehler, C., G. Hesser, and A. Weigert. 1983. A study of articles on religion in major sociology journals, 1978-1982. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 11:165-170.

Clear, T. 1991. “Prisoners and Religion,” Interim Report, Executive Summary. School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, New Jersey.

Clear, T., Stout, B., Dammer, H., Kelly, L., Hardyman, P., Shapiro, C. 1992. “Prisoners, Prisons and Religion,” Final Report, School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, New Jersey.

Craigie, F.C., I.Y. Liu, D.B. Larson, and J.S. Lyons. 1988. A systematic analysis of religious variables in the journal of family practice. Journal of Family Practice, 30:477-480.

Gartner, J., T. O’Connor, D.B. Larson, M.C. Young, K.N. Wright, and B. Rosen. 1990. Religion and Criminal Recidivism: A Systematic Literature Review. Paper presented at the meeting of the American Psychological Association, Boston, Massachusetts.

Gartner, J., Larson, D.B., and Allen, G. 1991. Religion and mental health: A review of the empirical literature. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 19, 6-25.

Hoffman, P.B. 1983. Screening for risk: A revised salient factor score (SFS 81). Journal of Criminal Justice, 11(6):539-547.

Hoffman, P.B., and Adelberg, S. 1980. The salient factor score: A non-technical overview. Federal Probation, 44(1):44-53.

Hoffman, PP.., and J. Beck. 1976. Salient factor score validation: A 1972 release cohort Journal of Criminal Justice, 4:69-76.

Johnson, BR. 1984. Hellfire and Corrections: A Quantitative Study of Florida Prison Inmates. Doctoral Dissertation, Florida State University, School of Criminology.

Larson, D.B., J.S. Lyons, W.M. Huckeba, G.L. Gottlieb, and Beardsley, R.S. 1988. A systematic review of nursing home research in three geriatric journals: 1981-1985. In M. Harper (ed.), Behavioral, Social, and Mental Health Aspects of Long-Term Care. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

Larson, D.B., Pattison, E.M., Blazer, D.G., Omran, AR., and Kaplan, B.H. 1986. Systematic analysis of research on religious variables in four major psychiatric journals, 1978-1982. American Journal of Psychiatry, 143:329-334.

Martinson, R. 1974. What works? questions and answers about prison reform. Public Interest, 10:22-54.

Martinson, R. 1979. New findings, new views: A note of caution regarding sentencing reform. Hofstra Law Review, 7:243-258.

Palmer, T. 1975. Martinson revisited. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 12:133-152.

Palmer, T. 1983. The effectiveness issue today: An overview. Federal Probation, 47:3-10.

Pritchard, D.A. 1979. Stable Predictors of Recidivism. Criminology, 17:15-21. Sampson, R., and Laub, J. 1993. Crime in the Making. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Scotnicki, A. 1992. Religion and the Development of the American Penal System, Doctoral Dissertation, Graduate Theological Union, Berkeley, California.

Stark, R., Kent, L., and Doyle, P. 1982. Religion and Delinquency: The Ecology of a “Lost” Relationship. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 19:4-24.

U.S. Parole Commission Paroling Policy Guidelines: 28 C.F.R. 2.20 and accompanying Notes and Procedures. 1984. In United States Parole Commission Rules and Procedures Manual, 25-72.

Wright, K.N. 1987. The Great American Crime Myth. New York: Praeger.

AUTHORS’ NOTES

Mark C. Young, Ph.D., has a doctorate in pastoral counseling from Loyola College. He is a United Methodist clergyperson and has a private practice in pastoral counseling and psychotherapy in Fallston, MD.

John Gartner, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist was associate professor in the Department of Pastoral Counseling, and Director of the Institute for Religious Research at Loyola College at the time of this study. Currently, he is assistant professor, Department of Psychiatry, Johns Hopkins University Medical School. He is also in private practice in Baltimore, and has published extensively in the area of psychology and religion.

Thomas O’Connor is an attorney from Ireland with an M.S. in pastoral counseling from Loyola College. He also has degrees in philosophy and theology and has worked on many church-related projects. He is director of the Center for Social Research, Inc., a non-profit research and consulting company based in Maryland, is completing a doctorate at the Catholic University of America, and is working on several research projects focusing on the role of volunteers and churches in the social reintegration of offenders and ex-offenders.

David Larson, M.S.P.H., is a research psychiatrist who spent ten years at the National Institute of Mental Health as a research epidemiologist. Currently, he is associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Duke University Medical Center. He has published extensively on mental health services and the relationship between mental health and religion.

Kevin Wright, PhD., is a criminologist and associate professor at the school of social work in the State University of New York at Binghamton. He has published extensively in the field of criminology and works as a consultant with the Federal Bureau of Prisons in Washington, D.C.. and in various other capacities within the criminal justice arena.

This study was carried out at the Institute for Religious Research, Department of Pastoral Counseling, Loyola College, Baltimore, under contract with Prison Fellowship Ministries.

Address correspondence to Thomas O’Connor, Center for Social Research, Inc., 5720 Tennyson Road, Riverdale, MD 20737.