What Works, Religion as a Correctional Intervention: Part II

by Thomas P. O’Connor*

Note: This is Part II of a two-part paper. Part I (JCC, Vol. 9, No. 1, Fall 2004) examined the history of the relationship between religion, crime, and rehabilitation and discussed the various theories regarding the impact that religion might have on reducing crime. This second part of the paper asks how religion works to rehabilitate offenders, explores the spiritual history and practice of incarcerated men and women and the religious process they go through while imprisoned, and reviews the empirical research about the effectiveness of religion as a correctional intervention.

Describing Religion as a Correctional Intervention: How Does It Work?

Shadd Maruna (2002) makes the point that correctional researchers and practitioners often ask the question “What works?” but fail to ask the equally, if not more, important question “How does it work?” about correctional programs. Much of the correctional evaluation research is focused on outcomes and tells us little about the processes that went into achieving those outcomes. In Part I of this paper (JCC, Vol. 9, No. 1, Fall 2004), I focused on the theoretical background for this “how does it work?” question. In this second part of the paper, I explore the spiritual history and practice of the men and women who are incarcerated in the Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC), describe the religious process that offenders go through while they are incarcerated, and review the empirical research about the effectiveness of religion as a correctional intervention.

Assessing Inmates’ Spiritual History at Intake

The ODOC is currently the only state department in the United States that keeps comprehensive data on the religious involvement of all of its prisoners while they are in prison. Also perhaps unique to correctional systems across the United States and Canada is the fact that the ODOC conducts a voluntary “spirituality assessment” alongside its criminogenic risk and need assessments for most new offenders who enter into the prison system at its intake center. This spirituality assessment process has helped to shed some light on the religious history and thinking of inmates who enter into a prison term, at least in the Pacific Northwest.

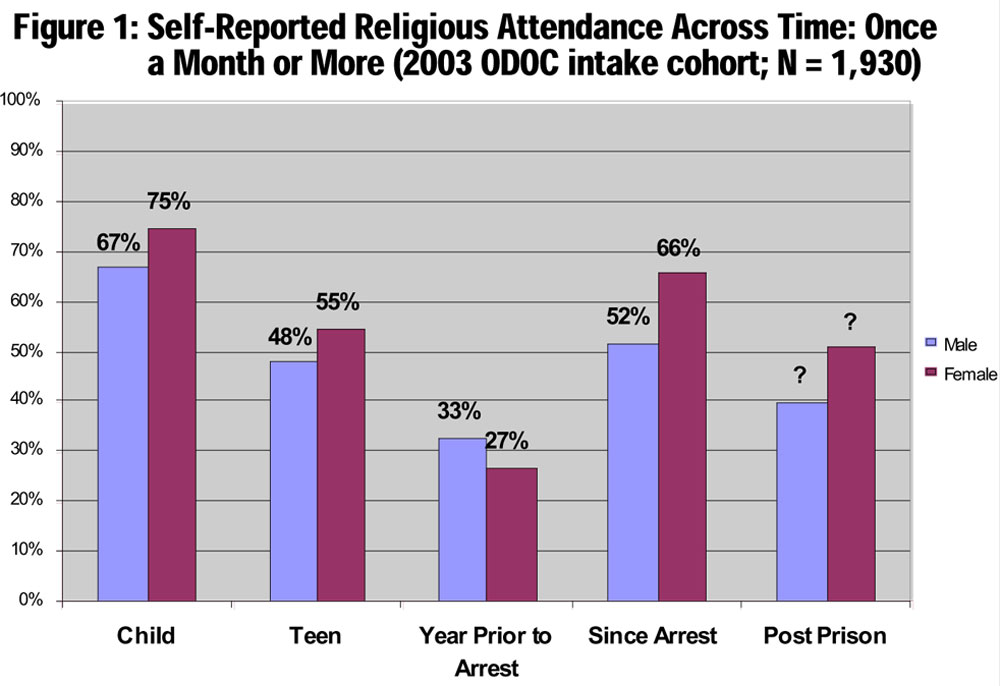

When asked if they were raised in a religious family setting, about one-third of both male and female inmates say “no,” one-third say “somewhat,” and one-third say “yes.1 Figure 1 shows how the self-reported levels of religious attendance vary over the lifetime for both the male and female inmates. Sixty-seven percent of the men and 75% of the women say they attended church, synagogue, mosque, sweat lodge, etc., once a month or more as a child. This figure drops to 48% for the men and 55% for the women during the teen years, and then to 33% for the men and 27% for the women during the year before arrest. Somewhat surprisingly, however, the self-reported rate of church attendance since arrest (once a month or more) climbs to 52% for the men and to 66% for the women. Research has shown that in the general population in America, there is a similar drop in religious attendance for most people from their childhood to their teen years. However, during their early adult years, their attendance level returns to a level that is higher than in their teen years but not quite as high as in their childhood years (O’Connor et al., 2002; Roozen, 1980).

Following a U Curve

In other words, the normal pattern of church attendance in the general population is a U curve. For the offender population, however, the pattern may have more of an extended downward slope, followed by a later upturn upon being arrested and entering jail or prison. Most likely, this delayed response is triggered by the fact that people, once arrested, tend to be in institutions that force them to get some control over their lives and to stay sober and drug free. In this new context, the normal questions of ultimate or religious meaning seem to emerge for inmates, just as they do for the general population in early adulthood.

The ODOC religious attendance records for the entire inmate population show that in any given month, about 32% of the rolling population attends at least one religious or spiritual service or activity. Over the course of a one-year period, this figure climbs to 52% of the rolling population, because of the fact that each month, new people begin participating. It is very difficult to compare this 32% monthly attendance or 52% yearly attendance rate to attendance rates for the general population in Oregon. However, one leading study of religious attendance across the United States estimated the religious attendance rate for the general population of Oregon to be about 9%. The percentage of individuals who are church, synagogue, mosque, or temple “adherents” in Oregon, as distinct from the religious attendance rate, is estimated to be 31% (Jones et al., 2000).

Religion in Prison Mirrors Practice in Community

The study by Clear et al. (1992) of 12 prisons in different regions across the United States found that religion in prison is much like the religion that is practiced in the community. Clear and colleagues found that people in prison, like people in the community, have both intrinsic and extrinsic motivations for participating in religious services. Intrinsic motivations for prisoners were:

- Dealing with guilt;

- Finding a new way of life; and

- Dealing with loss, especially of freedom.

Extrinsic motivations were:

- Safety;

- Material comforts;

- Access to outsiders; and

- Inmate relationships that are less stressful

In-Prison Religion More Intense

Clear et al. (1992) did find, however, that in-prison spirituality or religion differed in one significant way from religion in the community. In-prison religion was more intense, and this was due to the closed and controlled context of prison religion. The prison context served to heighten the religious experience of the inmates (and volunteers who provided the religious services) in much the same way, perhaps, as a religious experience would be heightened in a monastic setting. So the prison context seems to increase the religious and spiritual involvement of prisoners.

In-Prison Religion More Ethnically Integrated and Religiously Diverse

In my opinion, there are also two other ways in which in-prison religion differs from religion that is practiced in the community. It is more ethnically integrated, and it is more religiously diverse. When you are in prison, you cannot easily segregate yourself according to race, and so religious services in prison may tend to be more racially mixed than they are in the general community. Furthermore, in the general community, many people are familiar only with their own religious tradition, and they have no easy opportunity to witness or attend the religious services of other faith traditions or denominations.

Self-Reported Religious Denomination for Offenders at Intake to Oregon Prisons (N = 1,983)

This is not so in a prison setting, where you may walk down a corridor with Protestant, Catholic, Buddhist, and Muslim services all going on at the same time in different rooms, and all of these services are open to the entire prison population. So people in prison can easily explore and experience different religious traditions. Preliminary analysis of the data in Oregon suggests that people do, in fact, try out different religious groups, and this may be particularly true for the women prisoners. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of the religious denominations with which people self-identify at the point of intake into the Oregon State prison system. The largest number (55%) self-identify as Protestant, and there is a wide array of other self-identifications, including 10% Roman Catholic and 7% Native American.

Table 1 shows the number of different men and women (from a rolling population of 16,365 inmates) who attended at least one service of each different denominational group that provided services during 2003 in the ODOC.

| Table 1: Number of Individuals Attending Religious Services by Religious Group and Gender During 2003 in the ODOC |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Denomination | Female | Male | Total |

| Protestant | 1,009 | 5,683 | 6,692 |

| Seventh Day Adventist | 363 | 1,163 | 1,526 |

| Catholic | 244 | 912 | 1,156 |

| Native American | 172 | 818 | 990 |

| Jehovah’s Witness | 115 | 499 | 614 |

| Buddhist | 142 | 358 | 500 |

| Latter Day Saints | 172 | 311 | 483 |

| Earth-based | 93 | 363 | 456 |

| Muslim | 0 | 345 | 345 |

| Religion & Culture | 0 | 102 | 102 |

| Christian Science | 29 | 70 | 99 |

| Hindu | 0 | 55 | 55 |

| New Age | 0 | 46 | 46 |

| Jewish | 0 | 18 | 18 |

| Interfaith | 0 | 14 | 14 |

Distinguishing Between Spirituality and Religion

Religious research increasingly makes a distinction between spirituality and religion because there has been a modern trend among the general population to distinguish these two concepts (Zinnbauer et al., 1997). Many people will say, “I am not particularly religious, however, I am a spiritual person.” By saying this, people tend to mean that they do not attend organized religious activities, but they do feel that they have a sense of ultimate meaning in their life that is connected to a relationship they have with a divine or ultimate source of meaning. For many people, both spirituality and/or religion help to answer the major questions about life, such as purpose, death, sickness, and health. Despite this growing distinction between spirituality and religion, the majority of the general population, when given the choice, identify themselves as being both spiritual and religious. In other words, there is considerable overlap between these two concepts or dimensions of a person’s life.

In one study among the general population, 74% of the people surveyed said, “I am spiritual and religious,” 19% said, “I am spiritual but not religious,” 4% said “I am religious but not spiritual,” and only 3% said, “I am neither spiritual nor religious.” When asked the same question, the adult offenders at ODOC intake responded as follows: 57% of the men and 60% of the women said “I am spiritual and religious,” 25% of the men and 29% of the women said “I am spiritual but not religious,” 10% of the men and 5% of the women said “I am religious but not spiritual,” and 8% of the men and 6% of the women said “I am neither spiritual nor religious.”

Two things are striking about these figures. First, the percentage of people saying they are “spiritual but not religious” may be higher among adult offenders (These figures are merely suggestive of this fact, however, because the numbers are not a scientific comparison). Second, the vast majority of the general population (93%), adult male offenders (83%), and female offenders (89%) say they are either “spiritual and religious” or “spiritual but not religious.” Thus, very few of those sampled say they have no spiritual or religious life. So, once again, the offender population looks very much like the general population of America, who we know are extremely likely—86% in a 1999 Gallup poll—to say they believe in God.

Race and Attendance at Religious Services

Does race affect who attends religious services in prison? The answer, at least in the ODOC, is that it seems to for men, but not for women. The data show that 48% of Caucasian, 51% of African American, 61% of Hispanic, 64% of Asian, and 75% of Native American men attended at least one religious or spiritual service during a one-year period. The figures for women show that 86% of Caucasian women, 83% of African American women, 86% of His panic women, 71% of Asian women, and 86% of Native American women attended at least one religious or spiritual event during the same period.

Gender and Attendance at Religious Services

Gender also has an impact on who attends religious services. Overall, during a one-year period, 50% of the rolling male inmate population attended at least one religious service or activity, compared with 85% of the rolling female population. This higher attendance rate among women mirrors a higher attendance level among women in the general population. In more than 49 countries around the world, studies have found a pattern of significantly higher interest in religion and spirituality among women as compared to men (Stark, 2002).

More than 52% of Inmates Attended at Least One Service

To summarize the religious or spiritual involvement of prisoners in the ODOC, one can say that more than 52% of the rolling inmate population attended at least one service in a year (8,646 of 16,365), with the average attendance being about once a week. In all, these 8,646 prisoners spent more than 350,000 hours (I call this “pew time”) engaged in religious or spiritual activities. The cost of providing these religious services for the 8,646 prisoners was about $220 dollars per inmate per year. These religious activities were made possible by a religious services staff of 21 chaplains, two volunteer program staff, four support staff, and 1,300 volunteers. To put the cost of these religious services into some kind of context, Joan Petersilia (1995) estimates that quality correctional programs (i.e., programs that reduce recidivism) cost between $12,000 and $14,000 per inmate per year.

The Positive Influence of Pro-Social Volunteers

This brief examination of the extensive and diverse religious involvement of inmates in one prison system, along with the theoretical explanations from Part I of this paper, gives us some intimation of how spirituality and religion might work to help an offender in the process of desistence from crime. Religion as an intervention might work because it provides a huge amount of program time for inmates with pro-social chaplains and a large number of volunteers, in a communal context of meaning that helps people grow through a process of increased social learning, social attachment, and religious conversion or faith development. It also helps inmates deal with guilt, find a new way of life, and deal with the many losses involved with being incarcerated, especially the loss of freedom. Other benefits, which are not as “spiritual,” include the provision of a safe place, material comforts, access to outsiders, and a less stressful set of inmate-to-inmate relationships.

In-prison spirituality or religion was more intense than religion in the community, and this was due to the closed and controlled context of prison religion.

The Question of Truth: Does Religion Work as a Correctional Intervention?

The Macro Level

Sociologists of religion and criminologists have tended to consider the relationship between religion and the justice system under two broad categories. First, there has been a body of literature examining the relationship between the prevalence and type of religion in a given society and the amount of crime in that society (Ellis, 1995, 2002; Evans et al., 1995; Stark, 1984). This macro-level analysis seeks to determine, for example, whether a community with a high church-going rate has a lower crime rate than a community with a low church-going rate, or whether members of different religious faith groups such as Catholics, Protestants, and Jews have different rates of crime. Johnson et al. (2000) have referred to these kinds of studies as studies of “organic religion.”

The Micro Level

Second, the relationship has been examined from a more individual or micro-level focus. In this body of literature, the question is whether or not the type and amount of individual religious practice in a person’s life helps him or her to live a crime-free life or, more importantly for our purposes, turn from a life with crime to a life without crime (Baier & Wright, 2001; Clear et al., 1992; Evans et al., 1995; Johnson, 1984; O’Connor, Ryan, Yang et al., 1996; Sumter & Clear, 1998). Johnson et al. (2000) tend to call these studies of “intervention religion.” From a more theological and religious-studies point of view, the relationship between religion, crime, and rehabilitation has been examined by exploring the role that religious thinking and movements have played in the development of penal policies and practices (Erikson, 1966; Forrester, 1997; Gorringe, 1996; Grasmick et al., 1992; O’Connor, 1998, 2003). For example, one study described how a certain Christian theology about the relationship between the suffering and death of Christ on the cross and the concepts of satisfaction and atonement has provided emotional and intellectual support for the more retributive elements of penal strategies in the Western industrialized countries (Gorringe, 1996). In the next section of the paper, I will focus on the micro-level sociological and criminological approach to religion as an operative factor in the rehabilitation of adult offenders.

Little Research on Adult Offenders and Religion in Corrections

Despite the historically important role of religion in corrections, and the fact that religious practice is currently widespread in prisons, there is relatively little research on the topic as it relates to adult offenders (Gartner et al., 1990; Johnson, 1984; Sumter, 1999). Despite the paucity of research on the relationship between religion and adult offender rehabilitation, however, there has been considerable research on the relationship between religion and deviancy in the general population (Baier & Wright, 2001; Ellis, 1985; Knudten & Knudten, 1971; Sumter, 1999; Tittle & Welch, 1983). These studies usually relate to rates of crime as influenced by religious involvement or beliefs across different individuals, religions, denominations, communities, populations, or regions of the country. Most of them focus on religion and delinquency (drug use, petty crime, sexually acting out, etc.) among juveniles or college students. This body of literature, although not directly germane to the present review about religion and adult offenders, is of relevance because of what it has to say about the methodological considerations that need to be addressed in any study on religion and crime.

Failure to Establish Causality

In 1971, Knudten and Knudten (1971) reviewed the literature from approximately 1913 to 1970 and concluded that “empirical research is especially lacking in the areas of religion and juvenile delinquency, religion and crime, religion and corrections, and the role of religion in prevention”; they also said that “most research done in the area to date is insignificant scientifically.” In 1983, Tittle and Welch reviewed 65 different studies and found that only 10 of those studies failed to show a significant negative relationship between religion and deviance. In 1985, Ellis reviewed 32 studies and reported that five found no effect and 27 found a reduced effect for religious attendance on deviance. In 1999, Sumter examined 23 published studies that had examined the relationship between religion and deviance since 1985. Sumter found that five of these studies revealed no effect; however, 18 of the studies “produced evidence of a statistical[ly] significant and inverse relationship between some measures of religion and various indicators of deviance” (Sumter, 1999, p. 112). Importantly, however, Sumter also concluded that “although statistical[ly] significant associations were detected, the studies were not successful in establishing evidence of causality. This is a product of two inherent problems (research design and measurement error) and other methodological difficulties in studying religion and deviance” (p. 106):

- Research Design: Most of the research is not based on a theoretical explanation that develops a hypothesis to be tested. The research uses quasi-experimental designs at best, because it is generally not possible to use random experimental designs, and the designs tend not to investigate causal ordering over time.

- Measurement: Religion is difficult to measure, because it is a multifaceted phenomenon. This means that the operational definitions of religion vary widely in the literature, and quite often, studies fail to capture the many facets of the phenomenon because they use only a single indicator to measure religion.

- Statistical Analysis: Bivariate analyses tend to be the norm, especially in earlier studies, thus excluding the possibility of examining the issue of causality. Therefore, there is a need for more complex statistical models to fully explain the relationship between religion and deviance.

- Controls: The research tends to rely on case studies without good control groups or control variables and to find only moderate to weak associations. Furthermore, the research seldom attempts to explore the conditions under which religion might make more of a difference, especially with prison populations who are a special population that has not been the subject of much study.

“Empirical research is especially lacking in the areas of religion and juvenile delinquency, religion and crime, religion and corrections, and the role of religion in prevention.”

Positive Findings but Methodological Problems

In 2000, Johnson et al. conducted a systematic literature review to explore the religiosity and delinquency relationship in journal articles that were published between January 1985 and December 1997. Their review examined 40 different studies and found that one study suggested that religiosity increased delinquency, one study failed to specify an effect, three found a mixed effect, five found no effect, and 30 found negative or reduced effects. Johnson and colleagues also pointed out, however, that many of the studies had methodological problems. The studies generally did not use random sampling, did not use multiple indicators of religion, did not test the reliability of their measures, and did not use diverse methods to collect data for the operational representation of their constructs. Few of the studies, moreover, used longitudinal data.

Positive Association With Reduction Found Through Meta-Analyses

Finally, in 2001, Baier and Wright conducted a meta-analysis of this “varied, contested, and inconclusive” literature on the effect of religion on crime by reviewing 60 studies from journal articles, books, dissertations, and papers presented at professional meetings. Most of these studies were produced between 1969 and 1998. Nineteen of the 60 studies reported finding separate findings for associations between religion and both general index crime and non-victim crime. This meant that Baier and Wright analyzed a total of 79 measured empirical associations between religion and crime. Only two of these associations showed no relationship, whereas 77 showed a reduced relationship to crime. Baier and Wright summarized their findings by saying: “We found evidence that:

- Studies of religiously based samples produced significantly stronger estimates for the deterrent effect of religion, as per the moral-community hypothesis;

- Studies examining nonviolent crime found significantly stronger deterrent effects, as per the type-of-crime hypothesis; and

- Studies using small sample sizes and more racially diverse samples found stronger deterrent effects.”

Baier and Wright concluded that they found “solid evidence” that religious involvement had a positive association with preventing crime:

We examined data from 60 studies, and we found that religion had a statistically significant, moderately sized effect on crime of about r = –12. Since Hirschi and Stark’s (1969) finding of religious nondeterrence, many sociologists have questioned whether religion has any effect on crime. Our findings give confidence that religion does indeed have some deterrent effect (Baier & Wright, 2001, p. 16).

Strong Evidence of Effect but Methodological Limitations

Baier and Wright did not really discuss or examine the methodological limitations of the studies they reviewed. Table 2 shows that the overwhelming direction of the findings from all of the articles or studies that were described in these literature reviews are in the direction of showing a reduced or negative relationship between religion and deviance. This is strong evidence that there may be something important going on in this relationship. However, we must be very careful about interpreting these findings, because author after author has pointed out that the methodological limitations of these studies prevent us, in general, from making conclusions about causality.

Religion Not Included in Rehabilitation Studies

Because most of the studies referenced in Table 2 used samples drawn from the general population, usually adolescents or college students—and did not include offender samples—reviews of the correctional treatment literature have been silent about the religious variable. Thus, Martinson’s famous study of 231 rehabilitation studies did not include any studies of religion. Neither did an earlier review of 100 rehabilitation studies by Bailey nor a later review by Pritchard of 71 studies (Bailey, 1966; Martinson, 1974; Pritchard, 1979). This pattern of not including studies of the impact of religion on offenders in reviews of the empirical literature continues to this day; none of the more recent meta-analytical reviews of the correctional treatment literature has included religion as a variable (Andrews et al., 1990; Gendreau et al., 2001; Lipsey, 1995), although Lipsey is currently coding some studies on religion and corrections for a new meta-analytic review of the correctional treatment literature.

Although the overwhelming direction of the findings shows a negative relationship between religion and deviance, the methodological limitations of these studies prevent us from making conclusions about causality

Twelve Studies Examining Sixteen Associations

For this paper, I was able to locate 12 studies that examined approximately 16 important associations between religion and offenders’ rehabilitation from journal articles, dissertations, reports, and conference papers that have looked directly at the influence of religion on the rehabilitation of adult offenders (see O’Connor, 2003, for a more extensive review of most of these studies). These 12 studies tend to follow the same patterns as the wider body of literature on deviance and religion—that is, they provide some evidence of a significant relationship between religious involvement and rehabilitation but are accompanied by contradictory findings and weaknesses in research methodology that leave many questions unanswered and render inconclusive the findings about the nature of the relationship. Each of the 12 studies used either prison infractions or recidivism as its measure of rehabilitation. One study also used psychological adjustment to prison life as an additional outcome measure. Ten of the 16 associations examined in the 12 studies found evidence (with varying degrees of methodological support) of an overall positive impact of the religious involvement of prisoners on rehabilitation. Six of the associations studied found no overall program effect for the religious participation of prisoners on their rehabilitation. In four of these seven associations, however, the authors argue that they may have found some evidence of a program effect for some, but not all, of the subjects.

Studies Finding an Overall Positive Impact

First, eight studies, examining 10 associations, found some evidence of a positive impact of religious programming on rehabilitation. The numbers correspond to the studies listed in Table 3:

1a. Prison Fellowship (PF) Christian Ministry Program. Young et al. (1995) found that a Prison Fellowship (PF) Christian ministry program in the federal prison system had a significant long-term impact on reducing rearrest and time to rearrest over an 8- to 14-year follow-up period. Prison Fellowship, the largest program of its kind, is the international prison ministry organization that Charles W. Colson, a former presidential aide to Richard M. Nixon, founded following his own incarceration in Federal prison on a conviction of obstructing justice (Colson, 1979). In FY 2001– 2002, Prison Fellowship reported an annual budget of $47 million and a ministry to some 200,000 prisoners in county jails, states, and federal prisons across the United States that was supported by 300,000 volunteers (Prison Fellowship Ministries Annual Report 2001–2002). The Young et al. study also found that gender, race, and risk of recidivism interacted with religious involvement and that the program effects were concentrated among Caucasian men, women, and offenders with a low risk of recidivism.

| Table 2: Literature Findings of Relationship Between Religion and Crime by Number of Associations |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Increased | No Effect | Mixed Effect | Reduced | |

| Tittle & Welch (1983) | 0 | 10 | 0 | 55 |

| Ellis (1985) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 27 |

| Sumter et al. (1999) | 0 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| Johnson et al. (2000) | 1 | 5 | 3 | 30 |

| Baier et al. (2001) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 77 |

| Note: Studies used mostly adolescent or college samples. | ||||

2a. High Religiosity Predicted Fewer Infractions. Clear et al. (1992) found that high religiosity directly predicted fewer infractions and indirectly (through lower depression) predicted better psychological adjustment in prison. Of particular interest is that the study findings were “prison specific.” Depending on the prison, there was a religious effect either on adjustment or on infractions but not on both. In some of the prisons, younger inmates seemed to work with religion to help them adjust psychologically; in others, older inmates appeared to work with religion to keep their number of infractions down (Clear et al., 1992; Clear & Myhre, 1995; Clear & Sumter, 2002).

3a. More Involvement Meant Fewer Rearrests. Sumter (1999) added 80 months of release data to a subgroup from the Clear et al. (1992) study and found that inmates who were more involved in religious activities in prison and believed more in a transcendent God were significantly less likely to be rearrested.

4a. Ministry Preparation at Sing Sing. A small exploratory study in New York’s Sing Sing prison found some evidence of a relationship between religious involvement in a master’s degree level ministry preparation program conducted by the New York Theological Seminary and higher levels of successful reentry into the community as measured by rearrest rates (O’Connor, Erickson et al., 1997; O’Connor, Ryan & Parikh, 1996).

5a. Christian Program vs. Vocational Training. A more in-depth exploratory study comparing recidivism for offenders in Brazil released from two prisons—one that placed a volunteer Christian-based program at its core and one that had a workbased vocational training program at its core—found evidence that the Christianbased programming may have resulted in lower rates of recidivism (Johnson, 2002).

6a. Prison Fellowship Christian-Based Aftercare. O’Connor, Su et al. (1997) found that inmates in a group (group A) who received a Prison Fellowship, Christianbased aftercare program, which began in a pre-release center and continued after release, were significantly less likely to have escaped (counted as a prison infraction) from the prerelease center than inmates who had applied for but did not receive the program (group B) and inmates who were eligible for but did not apply for the program (group C).

7a. Religious Participation and InPrison Infractions. O’Connor and Perreyclear (2002) collected religious attendance records on inmates in a South Carolina prison for a one-year period and found that frequency of religious participation was inversely associated with in-prison infractions.

8a. Religious Participation and Reincarceration. O’Connor (2003) collected religious attendance records on inmates in a south Carolina prison over a four-year period and found that the frequency of religious participation was inversely associated with both in-prison infractions and rearrest over an average 2.3 year follow-up period.

Of particular interest is that the study findings were “prison specific.” Depending on the prison, there was a religious effect either on adjustment or on infractions but not on both.

Studies Finding No Overall Positive Impact

Second, five studies examining six associations have failed to find any overall positive impact for religious programming on rehabilitation, but four of these studies claim to have found some evidence of a positive program impact of religion for some of the study subjects. Again, the numbers correspond to the studies listed in Table 3:

1b. Religiosity and In-Prison Infractions Among First-Time Inmates. Johnson (1984, 1987) found no significant relationship in a path analysis between self-reported religiosity, church attendance, or prison chaplain’s rating of inmate religiosity and amount of time spent in confinement for in-prison infractions among 782 men serving their first term of incarceration in a minimum security prison.

2b. Self-Reported Religiosity and InPrison Infractions. Pass (1999) found no influence of self-reported levels of internalized or intrinsic religiosity on in-prison infractions among 345 randomly selected inmates from the prison population at Eastern Correctional Facility in New York.

3b. Prison Fellowship Programs, Infractions, and Recidivism. Studies by O’Connor (1995) and O’Connor, Ryan, Yang et al. (1996) in New York found that religious involvement in three different Prison Fellowship ministry programs in prison had no overall relation to prison infractions or rearrest during a one-year follow-up period. There was, however, some evidence of a reduced relationship to recidivism for a small percentage (about 10%) of the Prison Fellowship group who had the highest rates of ministry participation. A secondary analysis of the data from this study by a different team of researchers confirmed the findings of no overall impact, but a possible impact on the Prison Fellowship subjects with the highest level of attendance (Johnson et al., 1997).

Johnson (2004) added an additional seven years of follow-up data to the original data collected in the New York prisons by O’Connor and colleagues. Johnson explored the original data in some novel ways to see if there was any program impact on the rearrest and reincarceration patterns over the longer eight-year follow-up period. Overall, Johnson was unable to find a program impact on the Prison Fellowship group compared to the matched comparison group on rearrest or reincarceration patterns. The Prison Fellowship subgroup members with the highest attendance levels, however, were rearrested at a slower pace during the first three years of follow-up but ended up with the same rearrest rates as the comparison group over the entire eight-year follow-up period.

4b. Prison Fellowship Christian-based Aftercare. As noted above, O’Connor, Su et al. (1997) found that a group of inmates (group A) who received a Prison Fellowship Christian-based aftercare program that began in a pre-release center and continued after release were significantly less likely to have escaped (counted as a prison infraction) from the pre-release center than those in group B (who had applied for but did not receive the program) and group C (who were eligible for but did not apply for the program). The program group as a whole (group A), however, had a higher rate of return to prison for a parole violation or new crime than group B, and approximately the same rate as group C, so there was no overall program effect on recidivism. The recidivism rates for the subgroup of subjects in group A who completed the program, however, showed some evidence that program completion may have been related to reduced recidivism for group A.

5b. InnerChange Freedom Initiative. A study of Prison Fellowship’s Christian-based InnerChange Freedom Initiative (IFI) prison program, which is run in a partnership with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, found no overall difference in rearrest or reincarceration rates for the program participants compared to several groups that were matched on factors including qualifying for the program, race, age, offense type, and the salient factor risk of recidivism score. “Simply stated, participation in the IFI program is not related to recidivism reduction” (Johnson & Larson, 2003 p. 18).” The program completers or graduates, however, had a significantly lower rate of rearrest and reincarceration during the two-year follow-up than the noncompleters and the comparison groups, and the study authors argue that this finding “represents initial evidence that program completion of this faith-based initiative is associated with lower rates of recidivism” (Johnson & Larson, 2003, p. 19).

Studies Too Diverse for Conclusions.

Because these 12 studies on religion and adult offender rehabilitation vary considerably in their methodological rigor, we cannot equate their findings or make definite conclusions, either positively or negatively, about the rehabilitative impact of religious participation on prisoners. Rather, the studies support a somewhat encouraging but ultimately agnostic stance on the rehabilitative effectiveness of the religious involvement of adult offenders that seeks more and better evidence. As a group, however, the studies have helped us to understand more about the impact of prison religion.

Intensity and Other Variables.

Prison religion varies considerably in its meaning, practice, and impact across individuals and prisons. Intensity of involvement (or “dosage” in treatment jargon) seems to be a crucial factor in whether or not religious involvement has an impact on offender rehabilitation. Furthermore, other variables such as gender, race, risk of recidivism, and prison context seem to profoundly influence the kind of impact that religion may have on rehabilitation.

Interaction Effects.

Although most of these studies did not examine the interaction effects of the program variable with other variables, it seems likely that much of the program impact, if there is one, may lie, not in the main effects, but in the interaction effects among religious involvement and the other variables such as criminal risk level, gender, race, age, and other educational, vocational, cognitive, and substance abuse programming taken while in prison. To go beyond the inconclusive nature of the current literature, future studies need to be more informed by theoretical considerations, collect better data, become more precise and multi-dimensional in their measurements of religion, increase their statistical power, and model the impact of religion on rehabilitation using better research designs and statistical methods (O’Connor, 2003; Sumter, 1999).

Table 3 sets out the main findings for each of these 12 studies and indicates my own subjective assessment of the methodological quality of each of the studies using a four-part rating of “poor,” “fair,” “good,” and “excellent.” I rate one of the studies “poor,” seven of them “fair,” five of them “good,” and none of them “excellent.”

When the subjects of the study self-select themselves for the religious group, the cause of any effects that are found may be, not the program or treatment, but whatever it was that led the subjects to choose that group.

Self-Selection Bias.

Each of the 12 studies in Table 3 has its own particular strengths and weaknesses from a scientific methodological point of view. The studies tend to differ in their data collection methods, research designs, and methods of measuring religiosity and rehabilitation. This makes it difficult to compare them, especially given the fact that some of the studies have better research designs and data than others. This variation in quality may also help to explain the different findings across some of the studies. The main methodological limitation of these studies is the usual limitation: they were unable to rule out the self-selection factor because they were unable to randomly assign the subjects to a “religious” and “non-religious” group, so all of the 12 studies suffer from what is called “self-selection” or “intervention selection” bias. This problematical feature arises in research when the subjects of the study are not randomly assigned to groups but, rather, self-select themselves to be in their groups. This methodological limitation means that the cause of any effects that are found may not be the program or treatment itself but whatever it was that caused the subjects to choose to be in the religious group.

Inadequate Measures of Religiosity.

Another crucial limitation to most of these studies is the inadequate and unreliable measures of religiosity that were used. In this paper, I have described the complex and extensive nature of the spiritual histories and practices of inmates in a prison setting. Many of the 12 studies in this review use very inadequate proxies to measure the religiosity of the subjects and almost fail altogether to measure the religiosity of the comparison groups, wrongly assuming that the comparison groups are “non-religious.” The widespread involvement of prisoners in religious and spiritual practices revealed in the ODOC data above shows that one cannot assume that members of the general inmate population who did not attend the particular religious programs under study are not religious.

Inadequate Measures of Religiosity.

Thus, many religious and spiritual factors are not controlled for in these studies. Many other factors that are also theoretically important to the outcome, such as involvement in prison work, educational, cognitive, and substance abuse programs, also tend not to be controlled for, or examined from an interactional perspective, in these studies. Finally, the theoretical ground or basis for the hypotheses examined in most of the studies is weak and not directly tested.

| Table 3: Does Religious Involvement Have an Overall Impact on Rehabilitation for Adult Offenders? |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological | Quality of the Research | Infractions | Recidivism | |

| A. Studies finding an overall positive impact | ||||

| 1a | Young et al., 1995 | Fair | Yes | |

| 2a | Clear et al., 1992; Clear & Myhre, 1995; Clear & Sumter, 2002 |

Good | * Yes | |

| 3a | Sumter, 1999 | Good | Yes | |

| 4a | O’Connor, Erickson et al., 1997; O’Connor, Ryan & Parikh, 1996 |

Poor | Yes | |

| 5a | Johnson, 2002 | Fair | Yes | |

| 6a | O’Connor, Su et al., 1997 (see 4b below) | Good | Yes | |

| 7a | O’Connor & Perreyclear, 2002 | Fair | Yes | |

| 8a | O’Connor, 2003 | Good | Yes | **Yes |

| B. Studies finding no overall positive impact | ||||

| 1b | Johnson, 1984, 1987 | Fair | No | |

| 2b | Pass, 1999 | Fair | No | |

| 3b | O’Connor, 1995; O’Connor, Ryan & Yang et al., 1996; Johnson et al., 1997, Johnson, 2004 |

Fair | No | No |

| 4b | O’Connor, Su et al., 1997 | Good | No | |

| 5b | Johnson & Larson, 2003 | Good | No | |

| Note: None of the studies was rated as Excellent using four methodological quality levels—Poor, Fair, Good, Excellent. | ||||

| * Clear et al. (1992, 1995, 2002) also found that religiosity indirectly predicted in-prison psychological adjustment through,lower depression. | ||||

| ** O’Connor (2003) found that religious involvement did predict less rearrest, but did not predict less reincarceration. I went,with the rearrest association for this review because it was the main outcome for the study | ||||

Religion and the Penal System

The conversation in this two-part paper has moved from historical research, through theory, to empirical research into religion as a correctional intervention. Religion as a correctional intervention has taken several different forms in its interaction with the evolving penal systems that have emerged within the history of the United States of America:

- The main sociological theoretical perspective that has been used to explain why religion should have a positive impact on reducing crime among offenders has been a social control thesis that posits a functional role for religion in creating pro-social communities and altruistic behavior.

- The main religious theoretical perspectives that have been used focus on individual sinful people who either must be forced to obey the rules of society or must undergo the kind of radical change of heart and personal morality that comes about only through a religious conversion experience.

I propose a combined theoretical framework that integrates and draws on sociological, criminological, and religious theories about:

-

- Social learning;

- Social attachment and informal social control;

- Religious conversion; and

- “Program integrity,” or the principles of effective correctional programming.

An examination of the literature on the nature, extent, and impact of the religious histories and practices of inmates reveals that spirituality and religion among the offender population are much like spirituality and religion among the general community. Offenders interact intrinsically with religion to give meaning to life, and extrinsically to find and build social support. Age, race, and gender all influence the type and extent of religious participation among inmates. The religious involvement of prisoners places them in contact with chaplains and religiously motivated volunteers who believe in rehabilitation, and who believe that there is a place for offenders in the general community. There is a growing body of research into the impact of spirituality and religion on the rehabilitation of adult offenders that suggests there is a positive impact. However, much of this research suffers from methodological weaknesses that prevent the establishment of causality.

This review has examined associations between religion and crime from 12 studies. Ten of 16 associations in these studies showed evidence (with varying degrees of methodological support) of an overall positive impact of the religious involvement of prisoners on rehabilitation. Six of the 16 associations showed there was no overall program effect on prisoner rehabilitation. This review of the research on religion as a correctional intervention also found strong theoretical support for the widespread popular belief that religion and spirituality might play a role in the rehabilitation of offenders.

Rehabilitation vs. Punishment.

The outcome studies to date, therefore, are encouraging, but they are not conclusive. Rather, the studies present more of an agnostic position that says we do not know whether or not the religious involvement of prisoners, as currently practiced, plays an effective role in reducing recidivism. Both religious programming and research into that programming need to improve if society is to benefit from the enormous potential that faith-based services, lives, and interventions have to offer to the correctional systems and cultures in the United States. Research and criminological theory has shown that the effectiveness of the U.S. correctional systems is hampered by too great an emphasis on a punitive approach to corrections, which prevents the widespread implementation of evidence-based treatment methods that effectively reduce recidivism. Paradoxically, however, despite the fact that many religious people volunteer to work on rehabilitation issues, there is a strain of religious thought that goes back to the origins of America that reinforces a punitive approach to corrections because it emphasizes the need to coerce obedience to maintain society in the face of sinful humankind and believes that God demands punishment to balance the moral order unbalanced by crime.

Offenders interact intrinsically with religion to give meaning to life, and extrinsically to find and build social support. Age, race, and gender all influence the type and extent of participation.

Value Beyond Recidivism Reduction.

Perhaps what is needed even more than improved religious correctional interventions and research is for the multitude of religious traditions within the United States to raise their voices to ask that U.S. correctional systems become more loving, and thus, more authentically religious in nature. In an insightful article called “The Value of Religion in Prison,” Clear et al. (2000) argue that we should not judge religion in prison solely, or even primarily, on the issue of program effectiveness. For “what qualifies as working in the spiritual realm is not precisely the same as what qualifies as working in the criminal justice realm.” Clear and his colleagues found that religion in prison helps to humanize a dehumanizing situation by assisting prisoners to cope with being a social outcast in a prison situation that is fraught with loss, deprivation, and survival challenges. Clear et al. argue that prison religion can thus be justified because it prevents the further deterioration of inmates.

I agree with this core insight, which places the ultimate value of in-prison religion beyond recidivism reduction.2 I would add, however, that in-prison religion may also help to prevent the deterioration of a society that seems to be focused on a widespread system of punishment that has little or no “medicinal” or rehabilitative effect. As an example, I present the following account.

Prior to being incarcerated, a homeless man had wandered into a mosque in Corvallis, Oregon, and had become acquainted with Islamic teachings and the people in the mosque. During his incarceration, he was a practicing Muslim and developed a relationship with the Islamic volunteers from the Corvallis mosque who, each week, faithfully visited the prison to hold Islamic services. The man’s name was Junid, and he died in prison in poverty, with only one surviving sister who lived far across the country. Normally, in this situation, Junid would have been cremated at the local funeral home with no one in attendance, and his ashes left on a shelf in the funeral home. Before Junid died, however, he had asked to be buried as a Muslim, and with the consent of his sister and the ODOC, the mosque sent people to sit with, wash, prepare, and take his body back to the mosque. After the regular Friday prayers in the mosque, the Islamic community held a funeral service for their dead brother, and about 200 people stayed to attend the service. Then, about 60 people went with the body to the only Islamic cemetery in Oregon and, at the expense of the mosque, buried their homeless friend facing east according to Islamic teachings. Recidivism in this case was not an issue, but the dignity, faithfulness, and compassion of Junid, his companions, and the ODOC were at stake. In a profound way, Oregon is a better place because of that dignity, faithfulness, and compassion.

Religion in prison helps to humanize a dehumanizing situation by helping prisoners cope with being a social outcast in a prison situation that is fraught with loss, deprivation, and survival challenges.

Endnotes

- We explain to the people taking the spirituality assessment that they may use words that best describe their experience in answering the questionnaire. For example, they may substitute the word “mosque,” “synagogue,” or “temple” for the word “church”; or the words “higher power,” the “divine,” etc., for the word “God”; and the word “spiritual” for the word “religious” in any of the questions we ask them.

- Prisoners, of course, like all other men and women in America, have a constitutional right (that is not lost when incarcerated) to practice and express their religion. So, whether or not religion “works” does not mean that it will disappear from prison life.

About the Author

*Thomas P. O’Connor, Ph.D., is administrator of religious services at the Oregon Department of Corrections.

This paper represents the views of the author and not necessarily those of the Oregon Department of Corrections or the International Community Corrections Association. The paper was written and funded under a technical assistance agreement (No. NICTA04C1071) with the National Institute of Corrections and the International Community Corrections Association. It draws, in part, on work conducted and studied by the religious services division of the Oregon Department of Corrections (ODOC).

The author would like to acknowledge the religious services staff in the ODOC for their dedicated work and, in particular, would like to recognize Frank Quillard, Jeff Duncan, and Ernest Harris for their crucial role in helping the religious services team examine and understand the meaning, extent, and role of its work in the ODOC. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the ICCA Annual Conference in Cincinnati, Ohio, on October 3–6, 2004.

References

Andrews, D.A., Zinger, I., Hoge, R.D., Bonta, J., Gendreau, P., & Cullen, F.T. (1990). Does correctional treatment work? A clinically-relevant and psychologically-informed meta-analysis. Criminology, 28(3), 369–404.

Baier, C.J., & Wright, B.R.E. (2001). If you love me, keep my commandments: A meta analysis of the effect of religion on crime. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 38(1), 3–21.

Bailey, W.C. (1966). Correctional outcome: An evaluation of 100 reports. Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, 57, 153–160.

Clear, T.R., Hardyman, P.L., Stout, B., Lucken, K., & Dammer, H.R. (2000). The value of religion in prison: An inmate perspective. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 16(1), 53–74.

Clear, T.R., & Myhre, M. (1995). A study of religion in prison. The International Association of Residential and Community Alternatives Journal on Community Corrections, 6(6), 20–25.

Clear, T.R., Stout, B.D., Dammer, H., Kelly, L., Hardyman, P., & Shapiro, C. (1992). Prisoners, Prisons, and Religion: Final Report. Newark, NJ: School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University.

Clear, T.R., & Sumter, M.T. (2002). Prisoners, prison, and religion: religion and adjustment to prison. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 127–159.

Colson, C. (1979). Life Sentence. Tarrytown, NY: Revell.

Ellis, L. (1985). Religiosity and criminality: Evidence and explanations surrounding complex relationships. Sociological Perspectives, 28(4), 501–520.

Ellis, L. (1995). The religiosity-criminality relationship. The International Association of Residential and Community Alternatives Journal on Community Corrections, 6(6), 26–27.

Ellis, L. (2002). Denominational differences in selfreported delinquency. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 185–198.

Erikson, K.T. (1966). The Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance. New York: Wiley.

Evans, D.T., Cullen, F.T., Dunaway, G.R., & Burton, V.S.J. (1995). Religion and crime reexamined: The impact of religion, secular controls, and social ecology on adult criminology. Criminology, 33(2), 195–224.

Forrester, D.B. (1997). Christian Justice and Public Policy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gartner, J., Larson, D., O’Connor, T., Young, M., Wright, K., Baker-Ames, D., et al. (1990). Religion and criminal recidivism: A systematic literature review. Paper presented at the American Psychological Association, Boston, MA, August 1990.

Gendreau, P., Goggin, C., Cullen, F.T., & Andrews, D.A. (2001). The effects of community sanctions and incarceration on recidivism. In L.L. Motiuk & R.C. Serin (Eds.). Compendium 2000 on Effective Correctional Programming. Ottawa: Correctional Service Canada.

Gorringe, T.J. (1996). God’s Just Vengeance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Grasmick, H.G., Davenport, E., Chamlin, M.B., & Bursik, R.J. (1992). Protestant Fundamentalism and the Retributive Doctrine of Punishment. Criminology, 30, 21–45.

Hirschi, T., & Stark, R. (1969). Hellfire and delinquency. Social Problems, 17, 202–213.

Johnson, B.R. (1984). Hellfire and corrections: A quantitative study of Florida prison inmates. Ph.D. diss. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University.

Johnson, B.R. (1987). Religiosity and institutional deviance: The impact of religious variables upon inmate adjustment. Criminal Justice Review, 12, 21–31.

Johnson, B.R. (2002). Assessing the impact of religious programs and prison industry on recidivism: An exploratory study. Texas Journal of Corrections, 7–11.

Johnson, B.R. (2004). Religious programs and recidivism among former inmates in prison fellowship programs: A long-term follow-up study. Justice Quarterly, 21(2), 329–354.

Johnson, B.R., & Larson, D.B. (2003). The InnerChange Freedom Initiative: A Preliminary Evaluation of a Faith-Based Prison Program. Philadelphia, PA: Center for Research on Religion and Urban Civil Society.

Johnson, B.R., Larson, D., & Pitts, T. (1997). Religious programs, institutional adjustment, and recidivism among former inmates in Prison Fellowship programs. Justice Quarterly, 14(1), 301–319.

Johnson, B.R., Li, S.D., Larson, D.B., & McCullough, M.E. (2000). Religion and delinquency: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice, 16, 32–52.

Jones, D.E., Doty, S., Grammich, C., Horsch, J.E., Houseal, R., Lynn, M., et al. (2000). Religious Congregations and Membership in the United States. Nashville, TN: Glenmary Research Center.

Knudten, R.D., & Knudten, M.S. (1971). Juvenile delinquency, crime, and religion. Review of Religious Research, 12, 130–152.

Lipsey, M.W. (1995). What do we learn from 400 research studies on the effectiveness of treatment with juvenile delinquents? In J. McGuire (Ed.). What Works: Reducing Criminal Reoffending. New York: Wiley, pp. 63–78.

Martinson, R. (1974). What works?—Questions and answers about prison reform. The Public Interest (Spring), 22–54.

Maruna, S. (2002). Making Good: How Ex-Convicts Reform and Rebuild Their Lives. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

O’Connor, T.P. (1995). The impact of religious programming on recidivism, the community and prisons. The International Association of Residential and Community Alternatives Journal on Community Corrections, 6(6), 13–19.

O’Connor, T.P. (1998). Best practices for ethics and religion in community corrections. The ICCA Journal on Community Corrections, 8(4), 26–32.

O’Connor, T.P. (2003). A sociological and hermeneutical study of the influence of religion on the rehabilitation of inmates. Ph.D. diss. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America.

O’Connor, T.P., Erickson, V., Ryan, P., & Parikh, C. (1997). Theology and community corrections in a prison setting. Community Corrections Report on Law and Corrections Practice, 4(5), 67–68, 75.

O’Connor, T.P., Hoge, D., & Alexander, E. (2002). The relative influence of youth and adult experiences on personal spirituality and church involvement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(4), 723–732.

O’Connor, T.P., & Perreyclear, M. (2002). Prison Religion in Action and Its Influence on Offender Rehabilitation. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 35(3/4), 11–33.

O’Connor, T.P., Ryan, P., & Parikh, C. (1996). The Impact of the New York Master in Theology Program on Recidivism: An Exploratory Study. Silver Spring, MD: Center for Social Research.

O’Connor, T.P., Ryan, P., Yang, F., Wright, K., & Parikh, C. (1996). Religion and prisons: Do volunteer religious programs reduce recidivism? Paper presented at the American Sociological Association, New York, August 1996.

O’Connor, T.P., Su, Y., Ryan, P., Parikh, C., & Alexander, E. (1997). Detroit Transition of Prisoners: Final Evaluation Report. Silver Spring, MD: Center for Social Research. Pass, M.G. (1999). Religious orientation and selfreported rule violations in a maximum security prison. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 28(3/4), 119–134.

Petersilia, J. (1995). A crime control rationale for reinvesting in community corrections. The Prison Journal, 75(4), 479–496.

Pritchard, D.A. (1979). Stable predictors of recidivism: A summary. Criminology, 17(1), 15–21.

Roozen, D.A. (1980). Church dropouts: Changing patterns of disengagement and re-entry. Review of Religious Research, 21(4), 427–450.

Stark, R. (1984). Religion and conformity: Reaffirming a sociology of religion. Sociological Analysis, 45(4), 273–282.

Stark, R. (2002). Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender differences in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(3), 495–507.

Sumter, M.T. (1999). Religiousness and post-release community adjustment. Ph.D. diss. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University.

Sumter, M.T., & Clear, T. (1998). An empirical assessment of literature examining the relationship between religiosity and deviance since 1985. Academy of Criminal Justice Sciences (March 14).

Tittle, C.R., & Welch, M. (1983). Religiosity and deviance: Toward a contingency theory of constraining effects. Social Forces, 61(3), 653–682.

Young, M., Gartner, J., O’Connor, T., Larson, D., & Wright, K. (1995). The impact of a volunteer prison ministry program on the long-term recidivism of federal inmates. Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 22(1/2), 97–118.

Zinnbauer, B.J., Pargament, K.I., Cole, B., Rye, M.S., Butter, E.M., Belavich, T.G., et al. (1997). Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36(4), 549–564.